To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.

版权 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

版权 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne –

This book borrows elements from different genres. First and foremost, there is this sense of seeing nature in a way that multiple senses are stimulated, a spirit that is captured in the new nature writing which is about a sense of time and place. The author makes this quite explicit as she writes in the introduction that it is about her way of seeing and feeling what surrounds her and her way of perceiving animals and their lives’. She adds that it is an attitude born out of empathy with the rest of the living beings with whom we share our surroundings. I can see the reason for making point of this this as sometimes even naturalists are a little detached and want to observe things at a distance or record them through our cameras. We have forgotten how when we as children actually liked to handle feathers and bones and feel their weight (or absence of it) and texture. Did it feel rough or smooth, did it feel light or heavy? We observe footprints in the mud but as adults we feel reluctant to touch and feel the wetness. Hopefully, this book may remind us that we are tactile creatures and reassure us that the next time we see a beautiful feather that it is ok to pick it up and run it though our fingers and marvel at the iridescence.

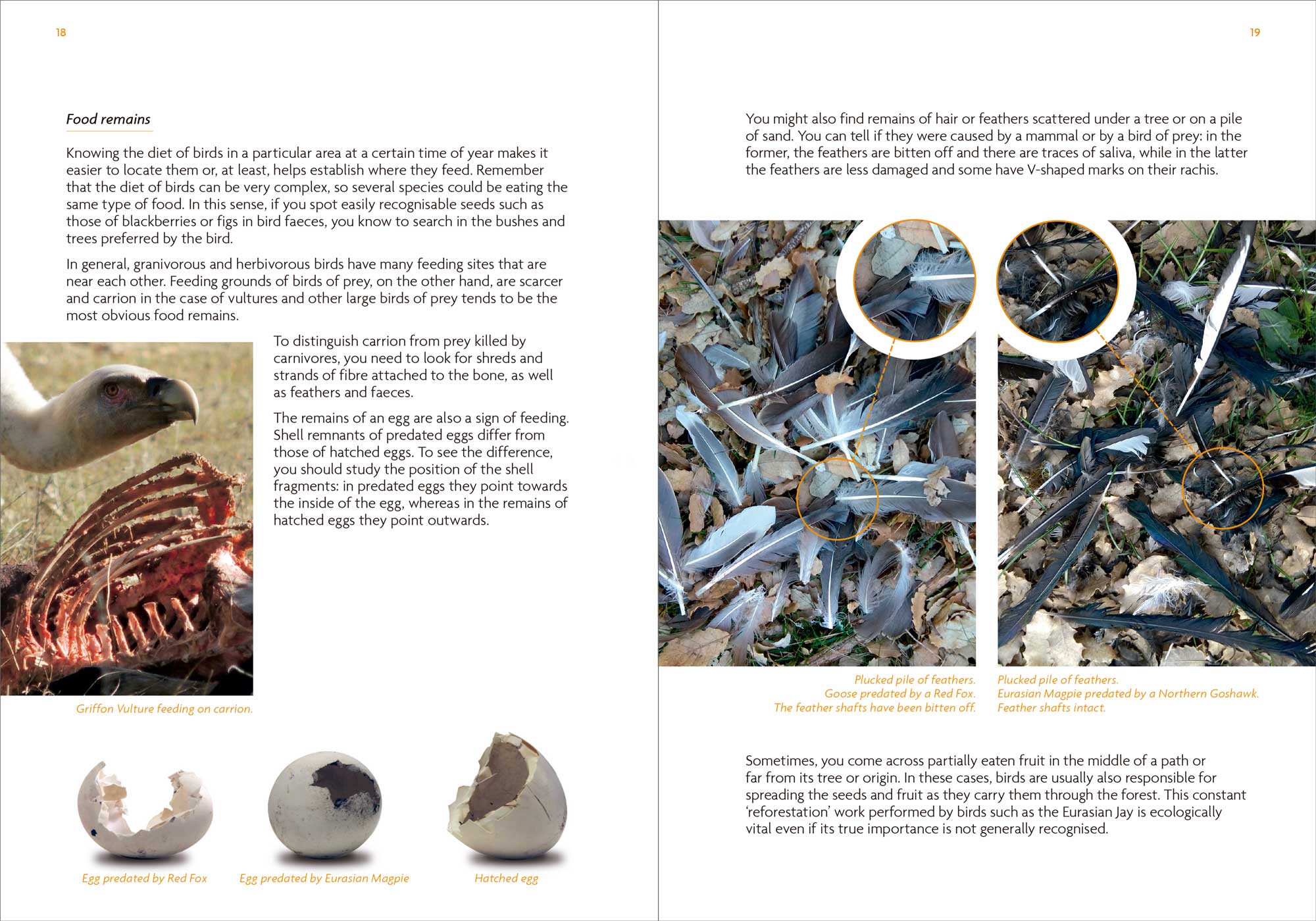

A second element of the book is that it is also about bushcraft. It took me back to Robert Baden-Powell’s influential book ‘Scouting for Boys’, first published in 1908. I devoured it as a young teenage schoolboy as it had a lot of interesting information on tracking animals. In a way it was a forerunner to some of the national park ranger training manuals of today which teaches bush craft to park rangers. There are ten pages on tracking birds by the signs they leave behind, not just footprints, but other signs. A thrush’s anvil leaves a tell-tale trail of smashed snail shells. Great Spotted Woodpeckers carry and leave behind pine cones at their ‘workshop’ where they can extract the kernels more easily. Crossbills leave a litterfall of pine cones after they have fed.

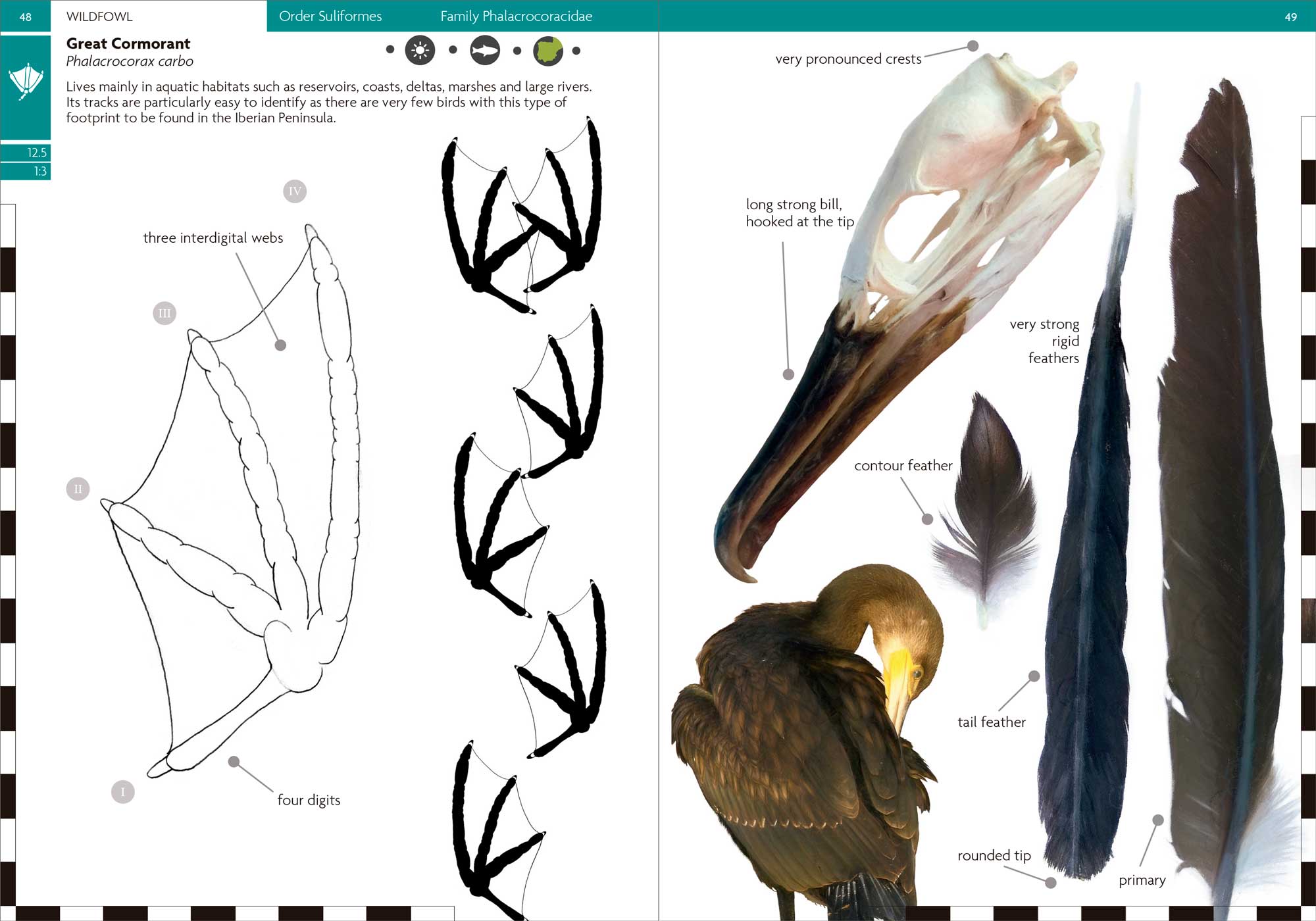

A third element of the books is that skulls and bones tell us something about an animal that may not be visibly obvious from the outside, but nevertheless has been engineered by evolution to lie beneath the skin and quietly perform its function. Katrina van Grouw in her book the ‘The Unfeathered Bird’ writes about and illustrates the bony projection that cormorants have on their skulls to attach the additional muscles which are needed for the birds to exercise a strong grip on fish with their un-serrated bills. Although not many birds have such a specialised feature, the shape of the skull and beak, the size of eye sockets, all tell us something about the modifications imposed on the design of the body by the individual lifestyle of a species.

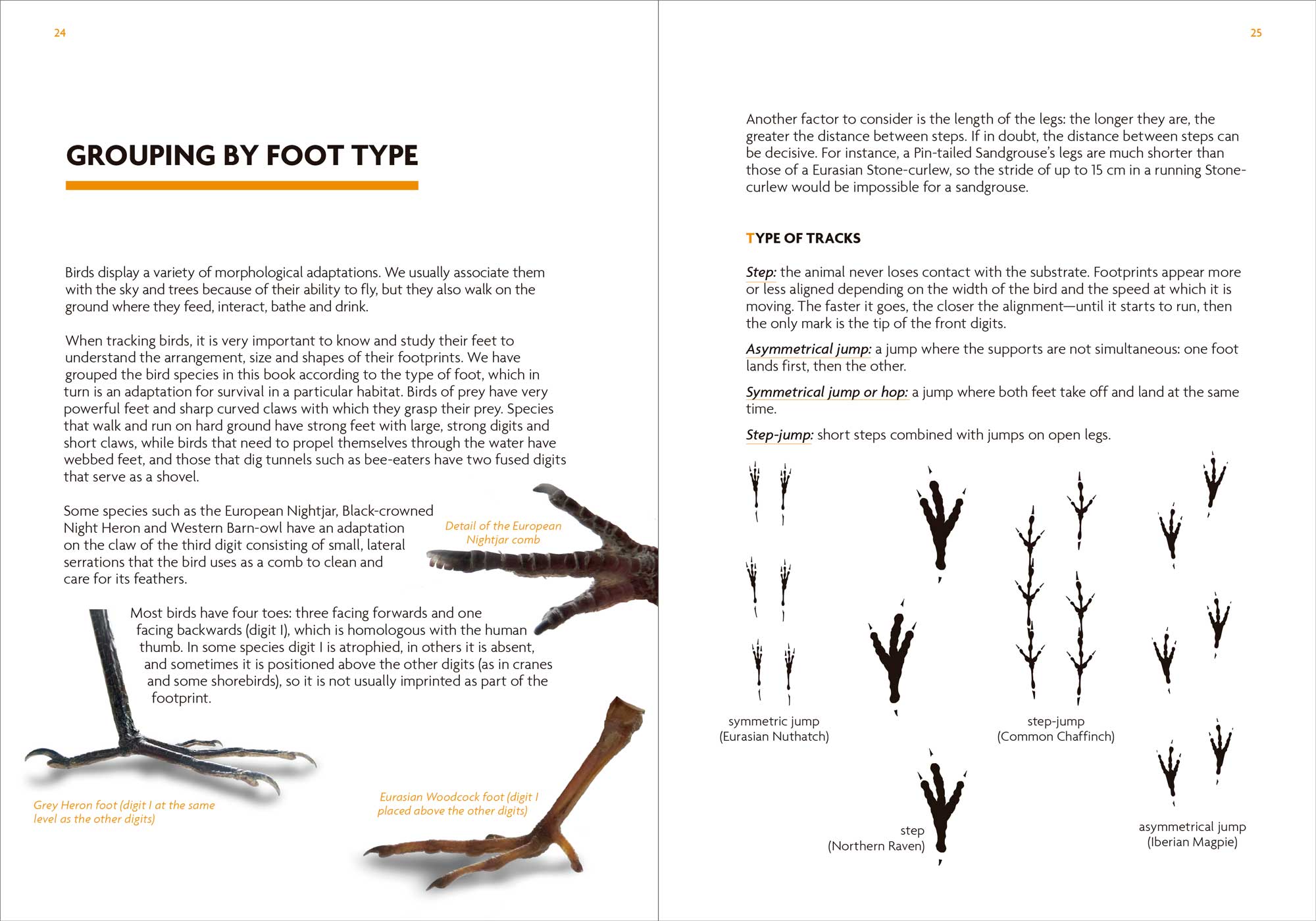

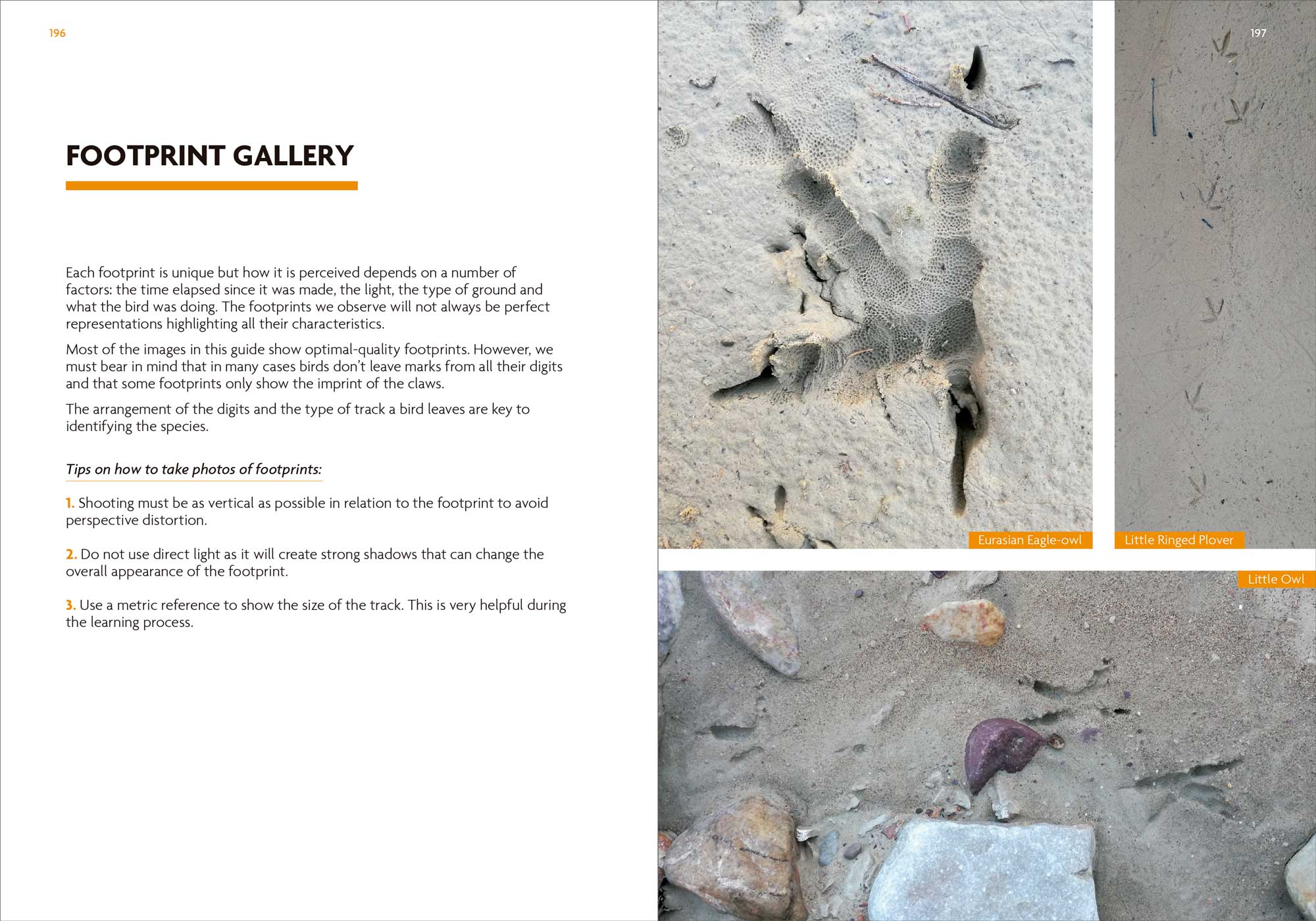

Thumbing through it, certain patterns emerge for example with the feathers. With tail feathers, the webs are fairly symmetrical around the central vane. With primaries, the outer web is narrow and the inner web broad. Each of the species’ accounts have diagrams illustrating the arrangements of the toes and the pattern of the footprints. There is also a gallery of photographs at the back end. This might encourage people who have the book to take pictures when they next encounter footprints in the mud and figure out whether the author of the tracks is a Curlew or Little Ringed Plover.

This book reminded me of a time in childhood when I had a book filled with feathers I had picked up. I had catalogued the sheets with the names of the species and the date of collection. I also had a mini museum (as did some of my peer group) with various bones and skulls I had collected on my walks. My collections and that of my friends was met with mixed feelings by parents. I think books like this are important to remind us that the presence of birds can be observed in ways other than through the use of optics. It also reminds us that we can enjoy the company of birds by also being alert to the signs they leave and we can pick up a feather the next time we see it and admire it for its aesthetic beauty or the biomechanical engineering imparted by evolution.