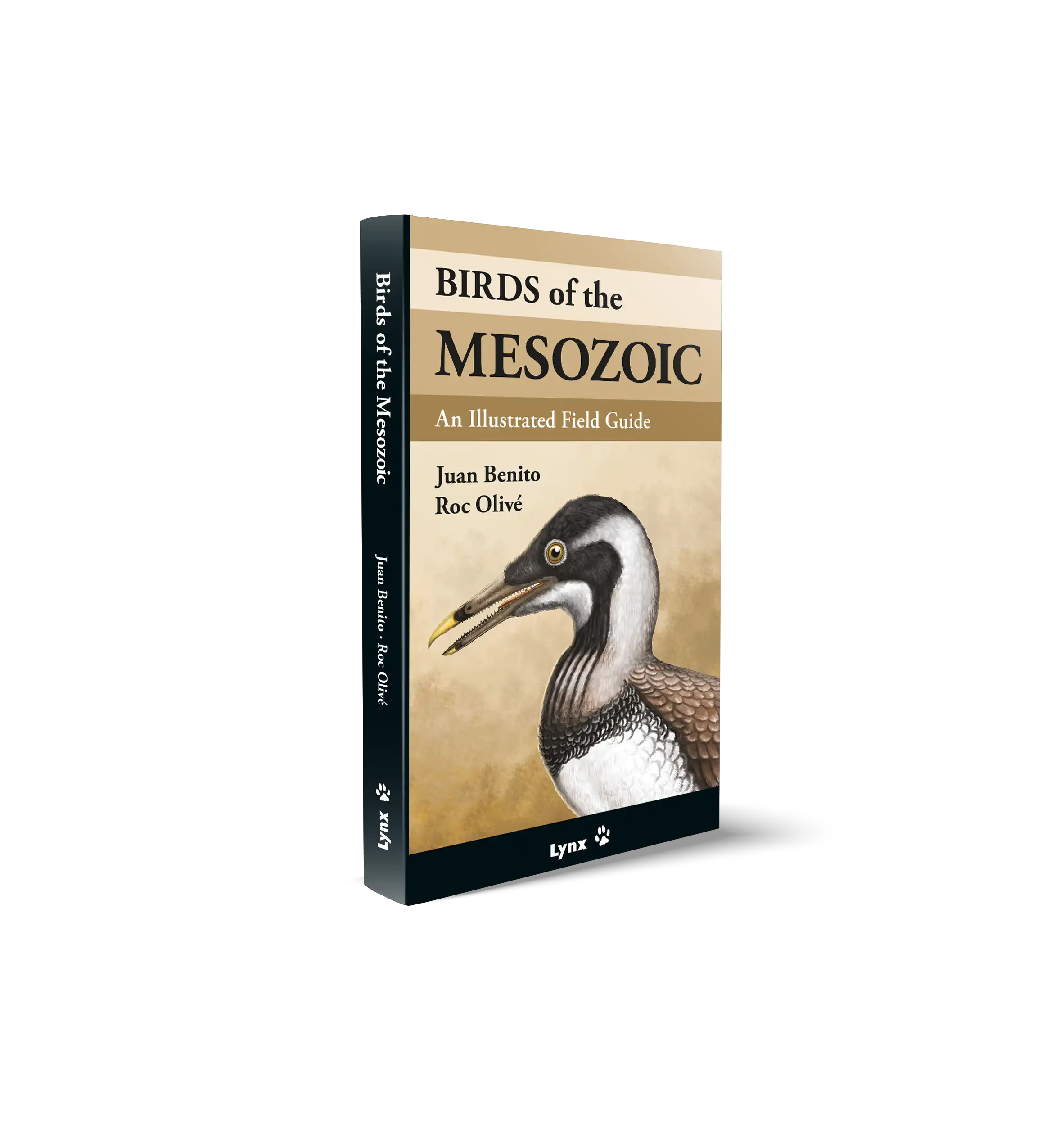

“胡安-贝尼托和罗克-奥利维在他们的新书中对中生代的鸟类进行了全面和最新的概述。这本指南包括对 200 多个物种的详细描述,并配有 250 多幅插图。此外,书中还介绍了这一时期鸟类的骨骼解剖学。对鸟类和古生物感兴趣的人一定会非常喜欢这本书”。

Ornis, 2023 年 3 月,第 38-39 页

重量

0.7 kg

尺寸

12 × 20 厘米

格式

Paperback

页面

272

出版日期

December 2022

出版商

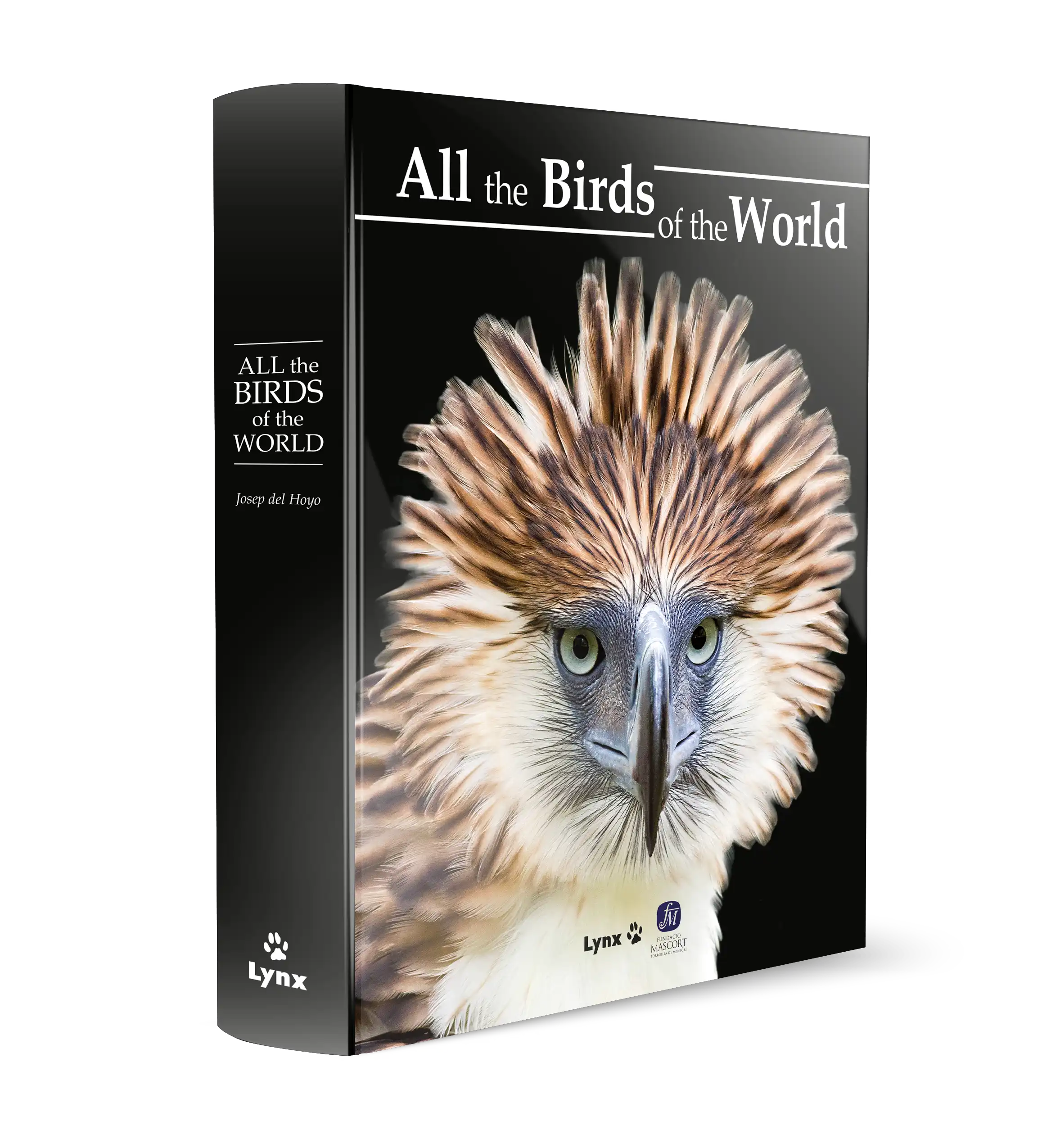

Lynx Edicions

说明

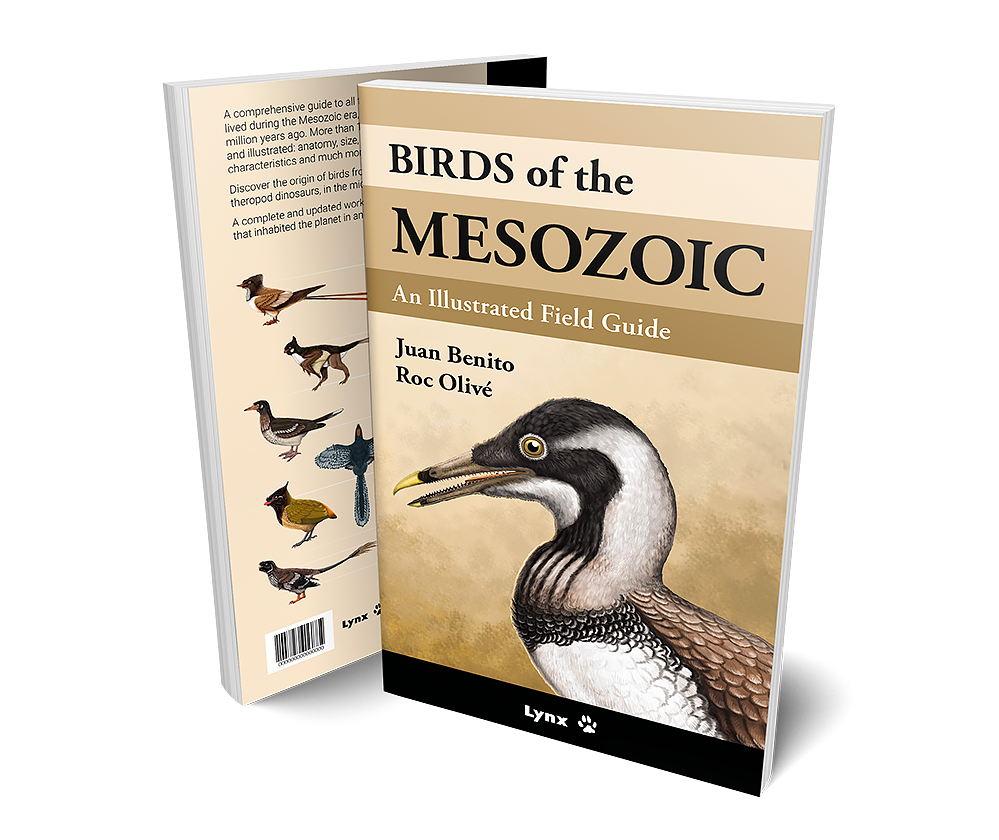

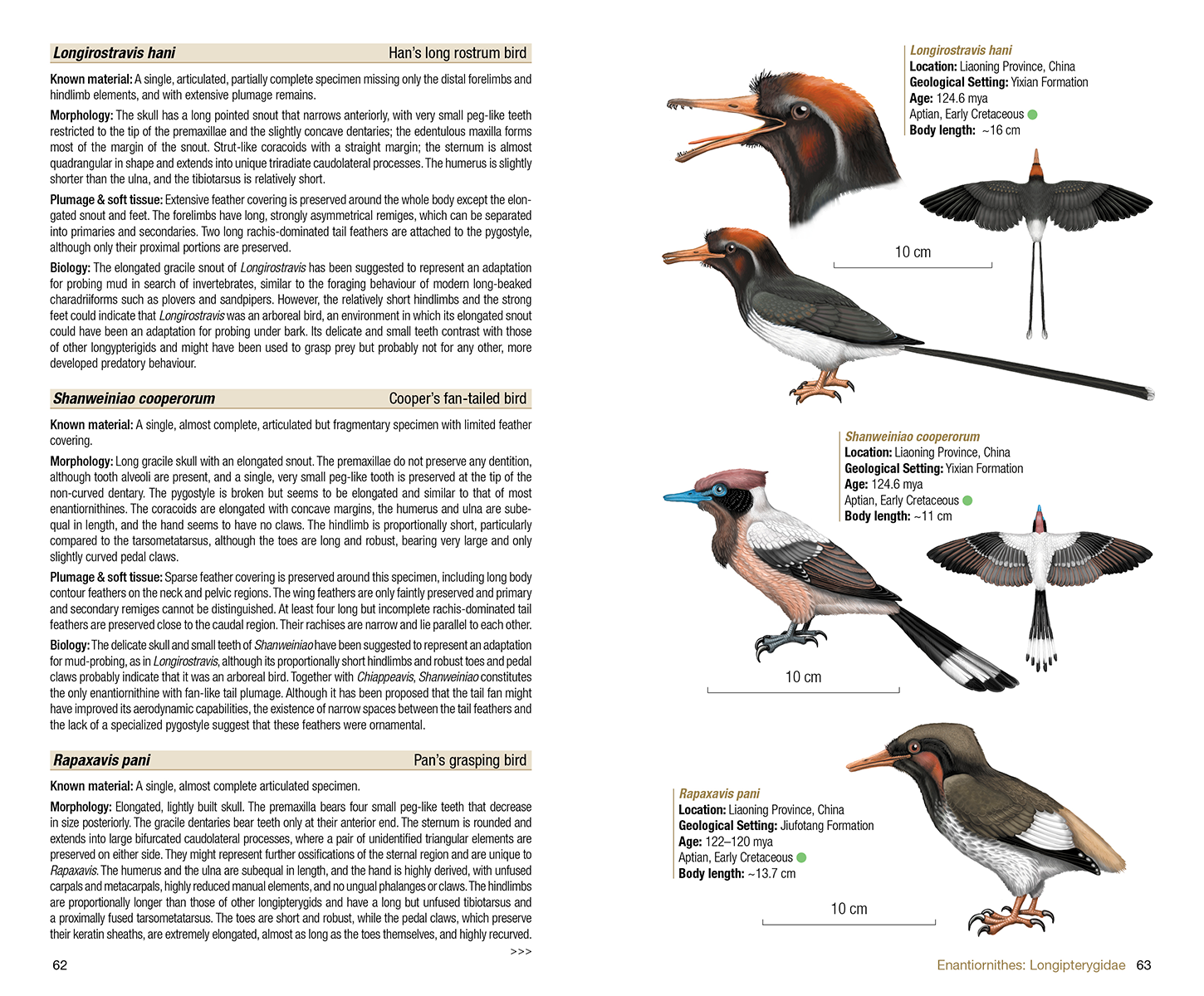

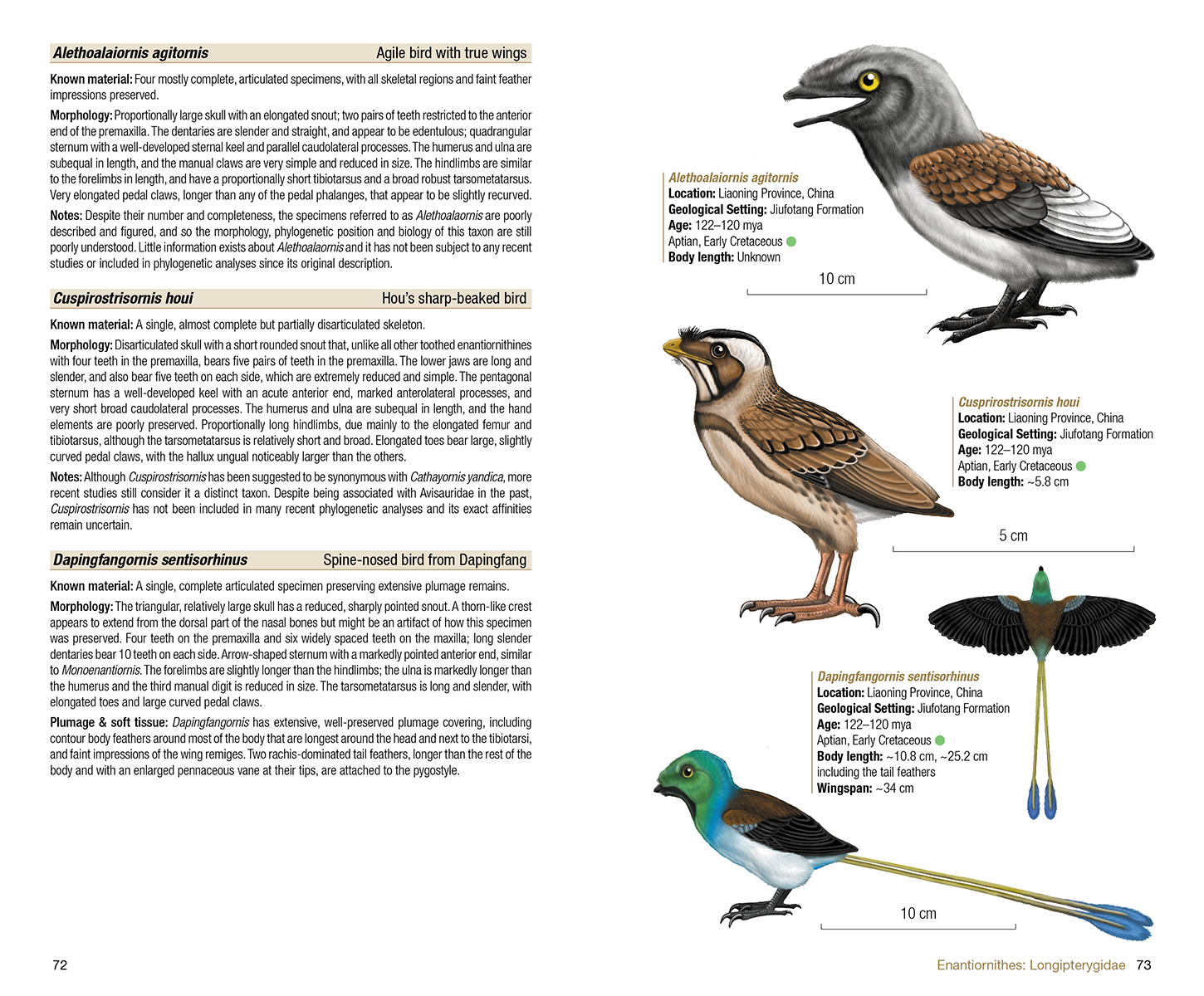

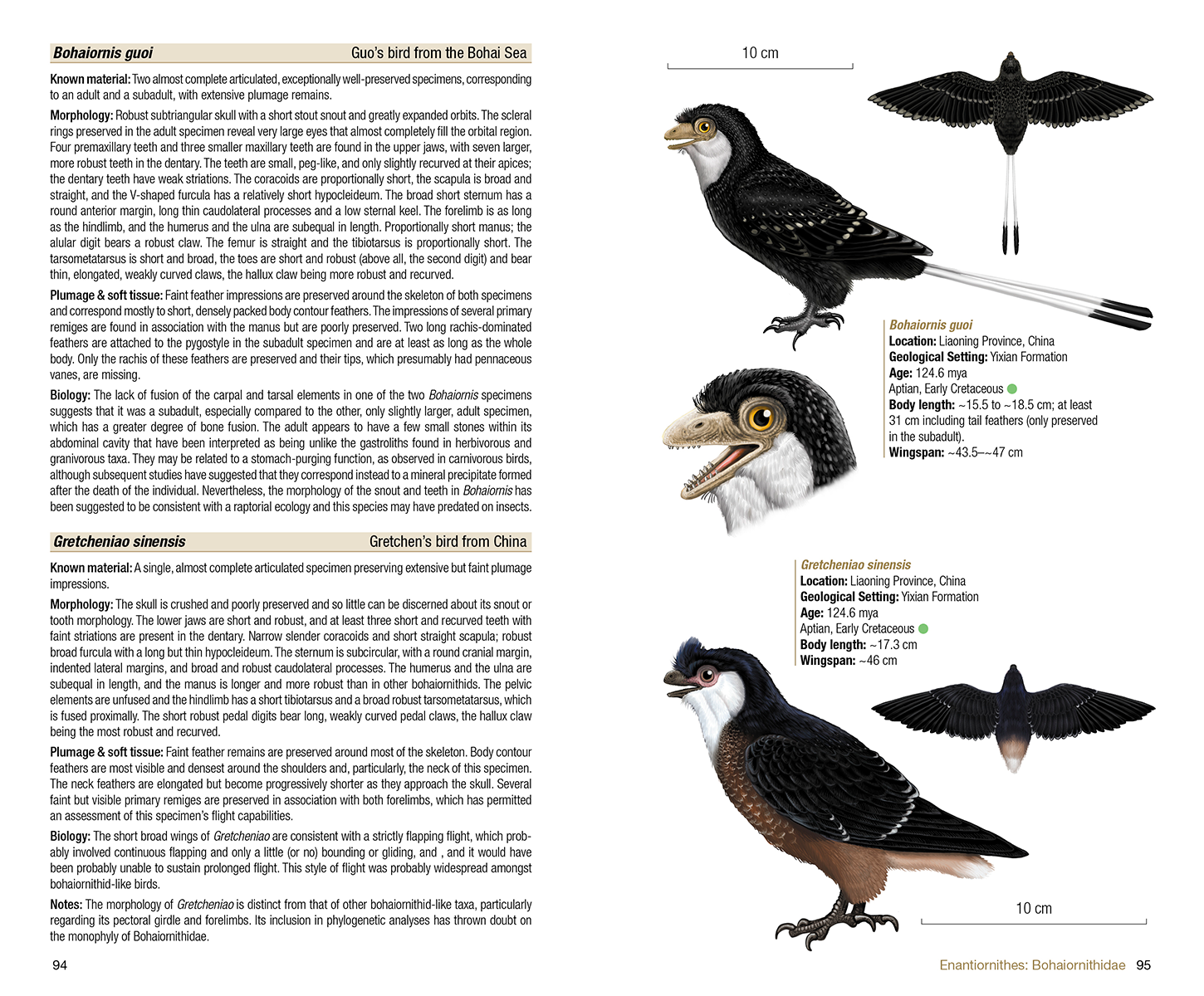

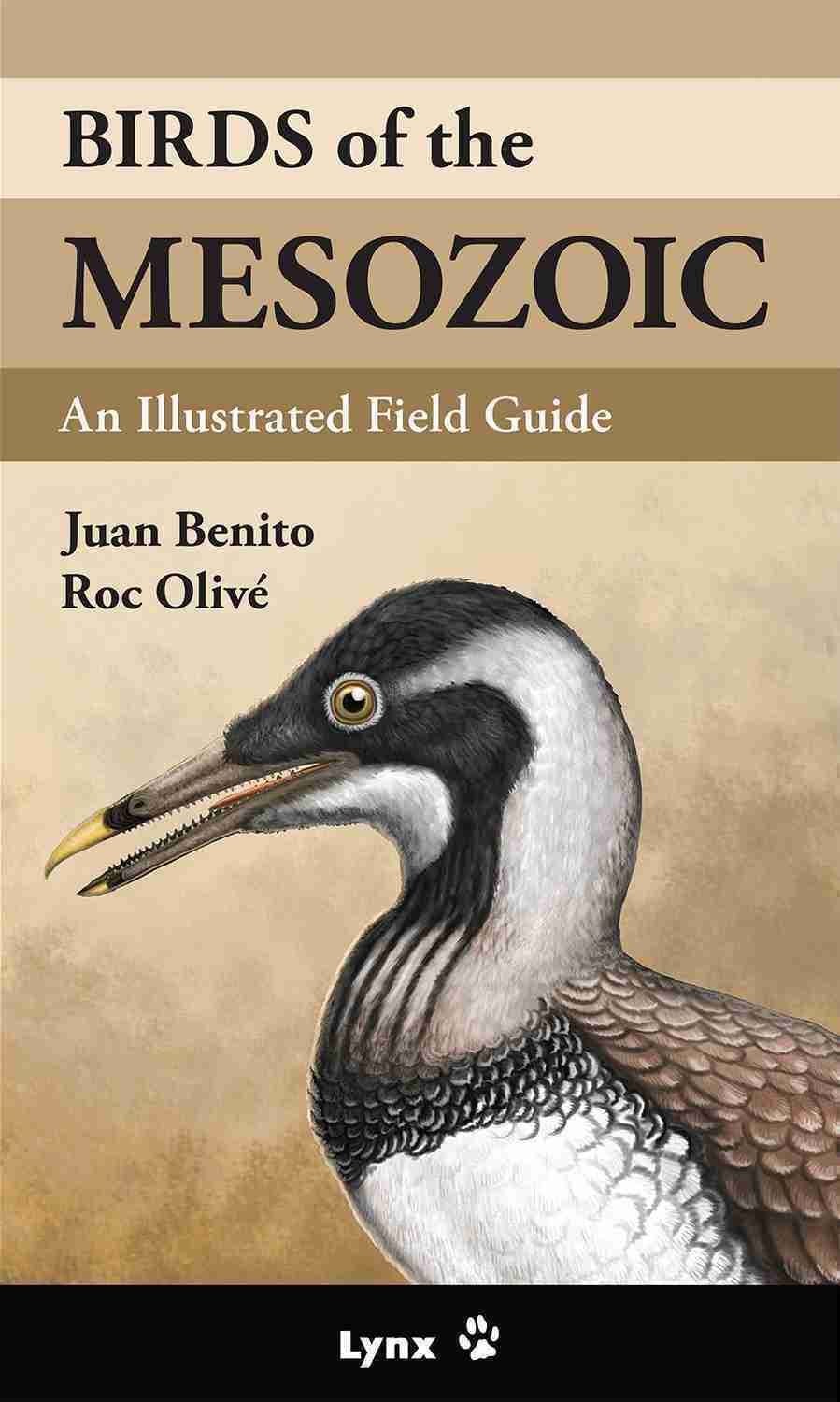

鸟类是当今最多样化的四足类群,但它们有着丰富而复杂的进化历史,超越了其现代辐射。 鸟类出现在距今 1.6 亿多年前的侏罗纪,在恐龙时代,鸟类飞上天空,进化成各种形态。 这本由古生物学家胡安-贝尼托(Juan Benito)和古美术家罗克-奥利维(Roc Olivé)撰写的图文并茂的综合野外指南,旨在以前所未有的详尽方式展示鸟类(现代鸟类及其近亲化石)的惊人多样性,这些鸟类从鸟类的起源一直生活到 6600 万年前的大灭绝(大灭绝结束了非鸟类恐龙的统治):中生代鸟类。

这本图文并茂的野外指南包含 250 多幅全彩插图,涵盖了中生代世界上的 200 多种鸟类。 除了详细介绍中生代各种鸟类的概况,包括每个物种的描述,以及名称、地点、大小、时期、栖息地和一般特征等信息外,这本指南还试图解释鸟类的起源,以及它们从其他有羽毛恐龙到晚白垩世现代鸟类起源的演变过程。 本书还详细介绍了鸟类系统发育、形态和生态多样性的多个方面,并介绍了鸟类骨骼解剖学以及古生物学家用来重建鸟类化石颜色、饮食和生物学的几种最新、最前沿的方法。

这本关于中生代鸟类的书简单易读,令人赏心悦目,是鸟类和古生物学爱好者的必备之书!

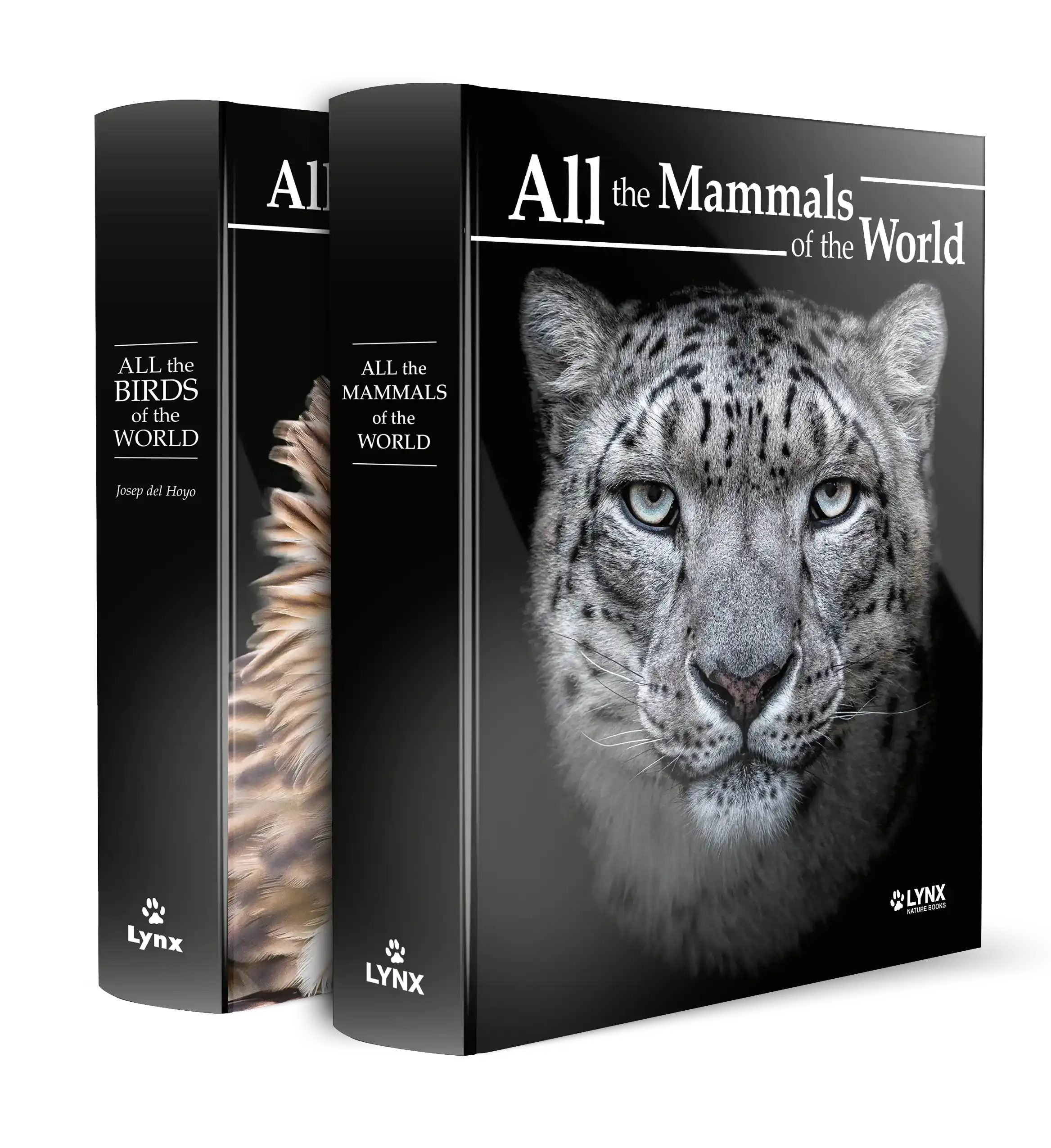

版权 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

版权 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne –

Headline: Good overview of avian palaeontology and a visual catalogue of Mesozoic birds

There are two audiences for this book, the Birds of the Mesozoic (BoM). Firstly, with those with a specialist interest in palaeontology who would like a catalogue of birds known from the Mesozoic. A catalogue of Mesozoic birds will be a moving target and the need for updated editions is no bad thing for a publisher. The second audience is people like myself, who don’t have a specific interest in palaeontology but have an informed layperson’s interest in evolution and the biology of living things, and especially so in relation to birds.

This book immediately brought to my mind two other books in my personal library. Firstly, the wonderful ‘The Bird: A natural history of who birds are, where they came from and how they live’ by the outstanding popular science writer Colin Tudge published in 2008. To set the scene for reviewing this book, I re-read his second chapter ‘How Bird Became’. Figures in Tudge’s book on the ‘Relationship of reptiles’ and ‘How the archosaurs gave rise to the birds’ helped me with context. It’s just the way my mind works, the forking diagrams with two branches at each node (cladograms) help me to visualise relationships and see the shared ancestry of birds and theropod dinosaurs.

Both Tudge and Juan Benito in their respective books refer to the relatively recent and explosive growth in our knowledge of the ancestors of living birds due to fossil discoveries especially from China. The second book that came to mind was ‘The Unfeathered Bird’ by Katrina van Grouw’. I purchased this book at the Linnean Society in London, soon after a lecture given by her. A purchase I have never regretted as it provided me with insights to point out a few things when I am leading nature walks for the London Bird Club, a section of the London Natural History Society. Van Grouw’s book is the opposite of Birds of the Mesozoic (BoM). Van Grouw takes us to the inside of living birds and helps us to visualise the internal skeleton and how it has evolved to serve a particular way of living. The ball and cusp wing joint of hummingbirds which allows them to rotate their wings is an example. But less obvious are structural changes in the Great Cormorant a familiar bird in London’s parks and the River Thames. I learnt that they have no external nostrils in the beak, which helps with their underwater feeding life style. Less obvious and only possible with a book that illustrates its skeletal structure was the spike-like, bony projection in the skull that allows strong muscles to be anchored. This is so that the bird can maintain a strong grip on muscular, slippery fish that are writhing in its bill. The cormorants have no serrations in their bill to help them. The BoM does the opposite, which is what palaeontologists have to do. They have to start with the inside and work out what the outside looks like. Sometimes they start with no more than a single bone to construct the exterior and work out its place in the evolutionary time scale. I had often wondered how this was possible with a single bone. This is all explained in an ‘Osteology’ section’ (pages 19 to 38) which is a sort of beginners guide to reading bird bones.

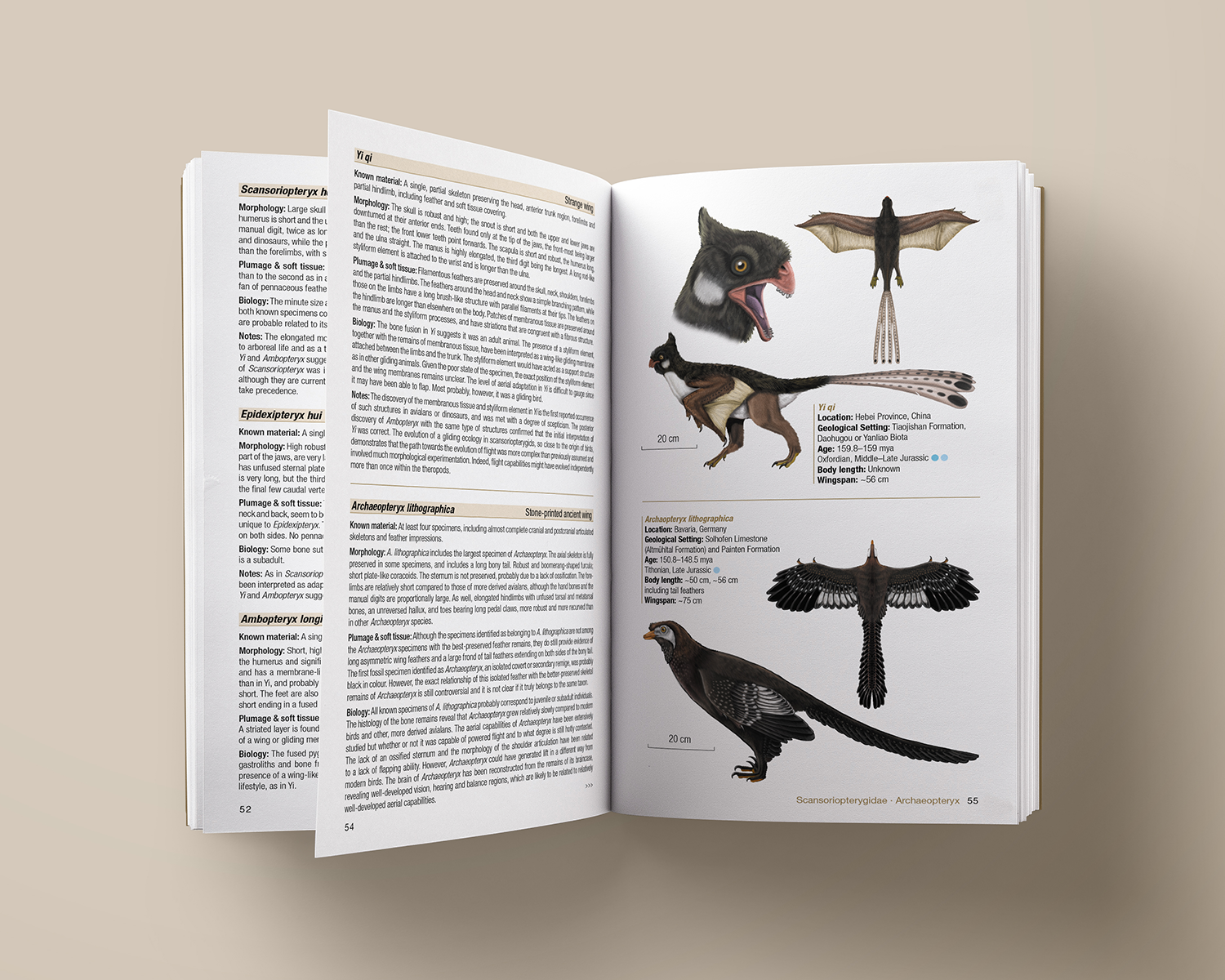

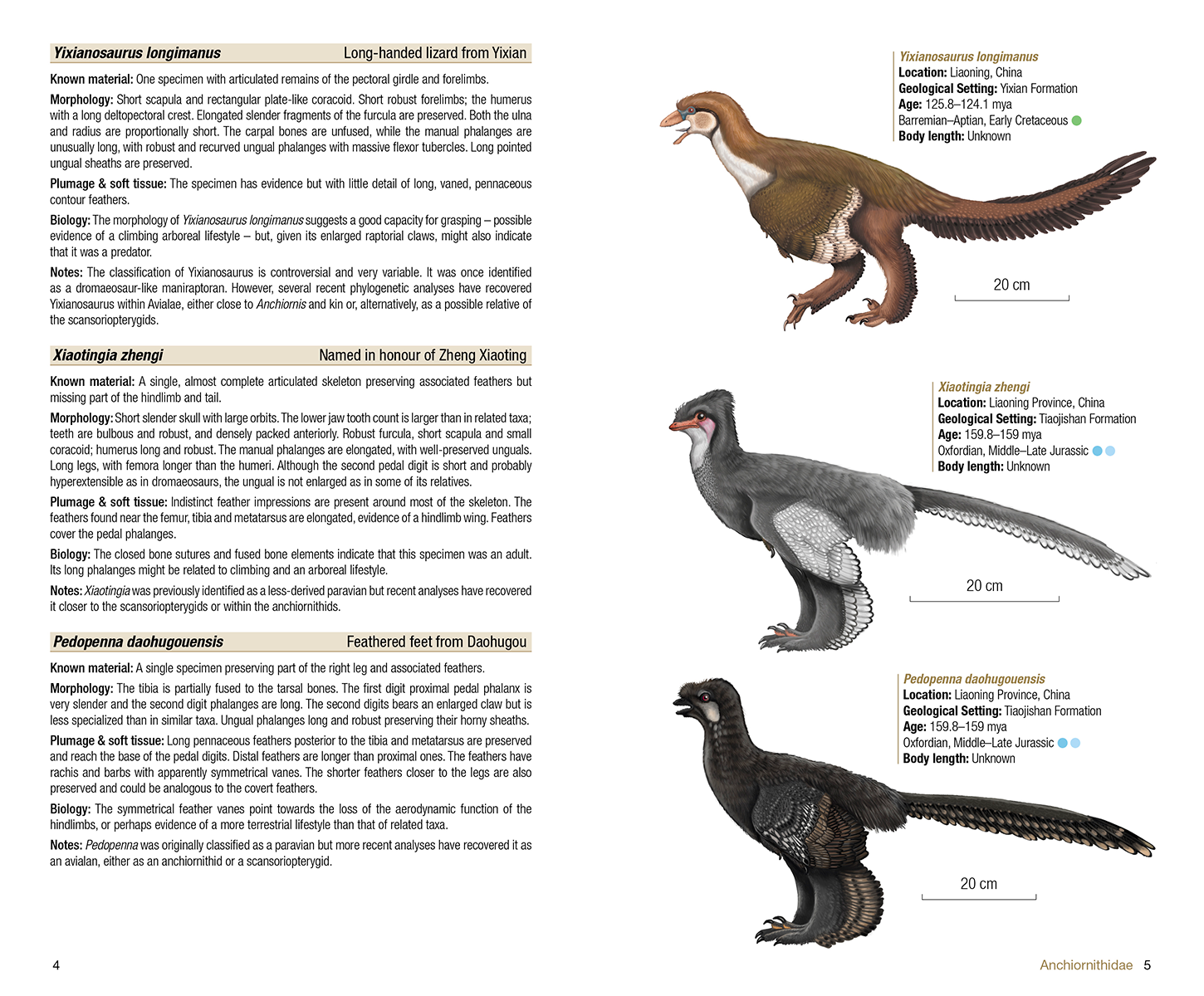

The first part of the BoM (pages 10 to 57) is a very useful overview of the evolution of birds and the evolution of key parts of their skeleton, especially those that support flight. The book begins by defining what is meant by a bird, as different concepts are in use when the term has to explain long extinct ancestors. The authors define birds as the clade Aviale or avialans. The first figure, a simplified phylogeny shows the Aviale branching off from other lineages that led to other theropods, Dromaesauridae and Troodontidae. The first 3 figures which show phylogeny at different levels of detail are important for understanding the field guide section which is arranged in the order of the phylogeny with section dividers at higher level taxonomic divisions for orders and key families. These sections are preceded by introductory text. The closer a lineage is to the original branching point, the more they are similar to the ground dwelling dinosaurs from the movie Jurassic park. Further down the phylogeny, is an important node, the Pygostylia and within it are the Ornithothoraces which represents the avialans with advanced wing apparatuses, well-developed sterna and pectoral girdles. This comprises of the now extinct Enantiornithes (the introduction explains why they are called opposite birds) and the Euornithes. The latter has the clade Neornithes which contains all of the living birds. The Enantiornithes and Euornithes are the last two clades to be covered in the field guide and not surprisingly the extinct forms look similar to many living birds. Other main introductory sections include ‘Plumage’ which explains the discovery of microscopic structures which helps to reconstruct colours. The section on ‘Biology’ covers many aspects including the development of bones and why the fossil bones of young birds can be distinguished from mature adults.

A key point in all of the three books I have referenced is that birds as a vertebrate group are characterised by the ability for powered flight. This in turn has required profound changes to their skeletal structure in a few ways. Firstly, birds require powerful flight muscles. This has led to significant developmental changes of the furcula (wishbone), sternum (keel), pelvic girdle and forelimbs. They also needed to reduce weight. To achieve this, bones found in other vertebrates have been lost in birds, some have been fused or modified in other ways. The internal structure of bones have changed to make them as light as possible filled with air spaces and internal bracing. Teeth which require strong and heavy jaw bones have been lost and the jaws replaced with a strong but light bill. All of this took tens of millions years to happen gradually in a sequence that is reasonably evident in the fossil record. This is why sometimes a single important bone like a sternum is enough to place a fossil bird relatively accurately in the evolutionary pathway.

Skeletons comparing an Archaeopteryx with a modern pigeon (figure 4) shows the transformation that has taken place over a large span of time. Understanding how the skeletal features of living birds help to anchor muscles and support their lifestyle informs the process of constructing what a fossil bird looked like when presented with one or more key bones. The osteology section also has many figures illustrating skulls, sternal morphology, shoulder articulation, the avialan coracoid, avialan furcula, humeral morphology, pelvic girdle, hind limb etc. As you read through terms such as furcula (wishbone) and coracoids (a bone that connects the keel to the vertebral column and wing joins) becomes as familiar as primaries and secondaries are to a birder. As you read about how the bones changed to support powered flight, you begin to understand why it has been said that for a human to fly it will require a keel two metres deep. The next time I carve a roast chicken, I will have a deeper appreciation of how a chicken’s bone structure came to be.

Finally, the introductory part contains a section on the ‘Bird Fossil Record’ which introduces aspects of geology and has a map showing each of the main fossil bearing rock formations that have yielded Mesozoic bird fossils. For the faint hearted the first part of the book can feel like a crash course in medical forensics but if you have always been intrigued by how scientists can figure out so much from a few fossil bones the introduction is a marvellous exposition of how the science of palaeontology works. The introductory part of the book can very easily be spun off into another book with more diagrams and text boxes explaining the study of fossil birds.

The field guide part of the book arranges the Mesozoic birds into the taxonomic groups encountered in the first three figures in the introduction. The start of an order or family is flagged by a section in capital letters and typically a page of introductory text. The species accounts have a standard structure with text on the left facing the plates on the right, in the style of a modern field guide. Typically, three species are covered in a double page spread. The text has standard headings for known material, morphology, plumage & soft tissue, biology and notes. I found it interesting to randomly read accounts. But for a fuller appreciation you need to have read much of the introductory material.

The end sections include a list of fossil birds excluded from the book, a glossary and an extensive bibliography (a trademark of Lynx Edicions publications who do not skimp on this). The page area of the book is small and in a field guide size (200 mm height x 120 mm wide). Although it is a nice touch to produce it in a small field guide format, the small page area has resulted in a small font being used. That works fine if it was really a field guide when only small sections of text are read at a time in the field. However, as much of the material is an armchair read, I would have strongly preferred a larger font size and spacing that facilitates a comfortable read when a large number of pages are read in a single sitting.

With living birds, a birder can easily tell if the illustrations bear a good likeness to the actual bird. With fossil birds it requires additional skills to illustrate in a way which is true to what can be inferred through fossil material and the current state of science. From the acknowledgements it is clear that the author and the artist Roc Olivé collaborated to make the reconstructions scientifically acceptable. They are also aesthetically pleasing. The field guide section would have been a labour of love for the artist and author to put together and it is a clever idea to present a catalogue of known fossils in a way that is lively and visually interesting. It also an easier way to digest the phylogeny as presently understood however incomplete that would be.

Reviewing this book got me thinking again about how birds came to be. The next time I am at a waterhole in Africa or Asia, I will remember that elegant storks and ancient looking crocodiles share an ancestry that places the crocodiles closer to birds than to lizards. The last time I walked along the River Thames, I noticed the long necks in Mute Swans and Great Cormorants. With birds we take it for granted that species in multiple families have long necks. But this is unusual in other vertebrate groups. Birds are quite a special group of vertebrates and this book helps to reinforce that.