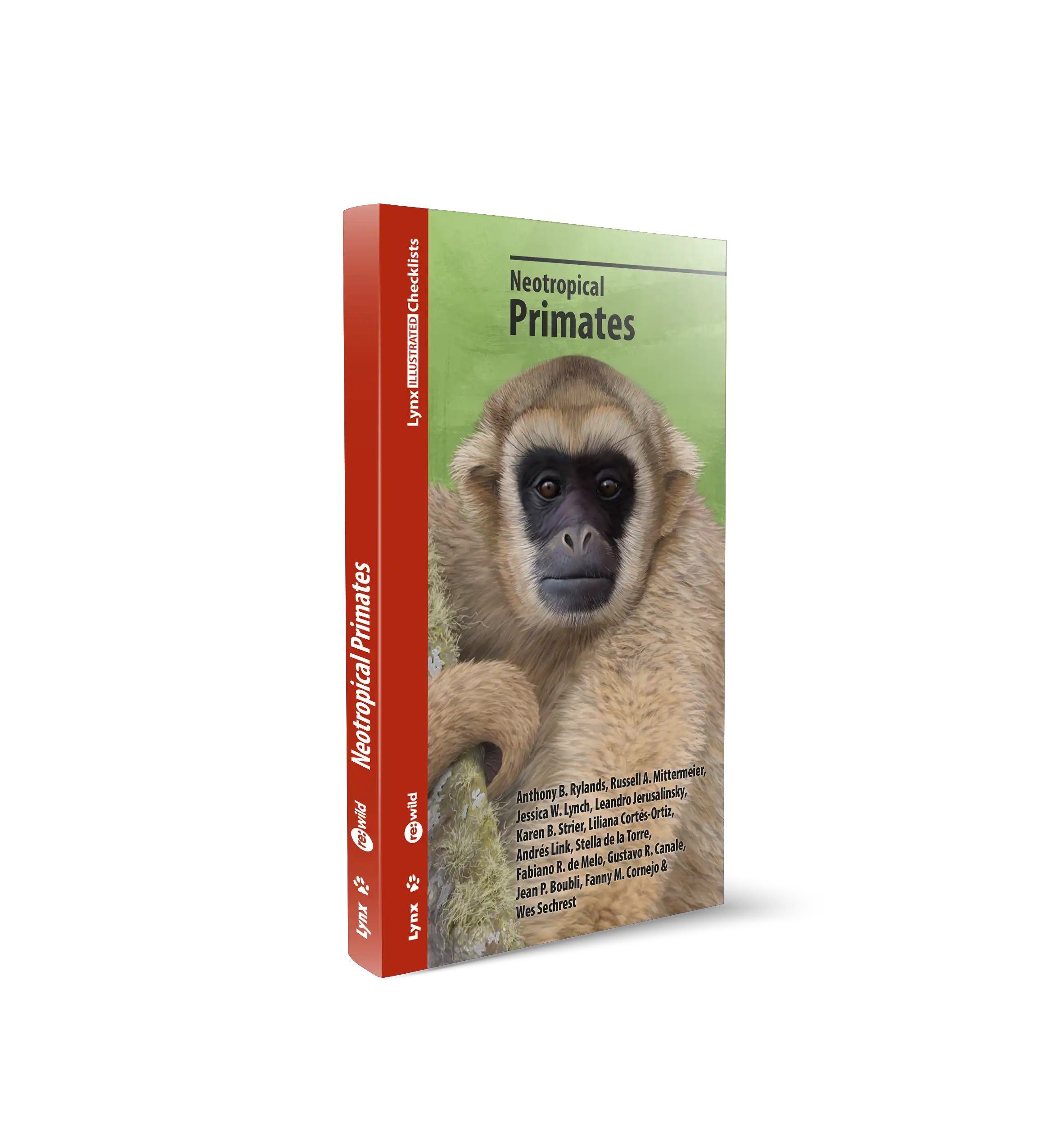

Neotropical Primates

$30.72

Autores

Ilustradores

En stock

$30.72

“Este práctico y compacto (140 páginas) manual de campo es imprescindible para cualquiera que visite el Neotrópico en busca de primates”.

Jon Hall, Mammal Watching, 20 de diciembre de 2024

Peso

0.45 kg

Dimensiones

14 × 22.8 cm

Idioma

Inglés

Formato

Rústica

Páginas

142

Fecha de publicación

September 2024

Publicado por

Lynx Nature Books

Autores

Ilustradores

Description

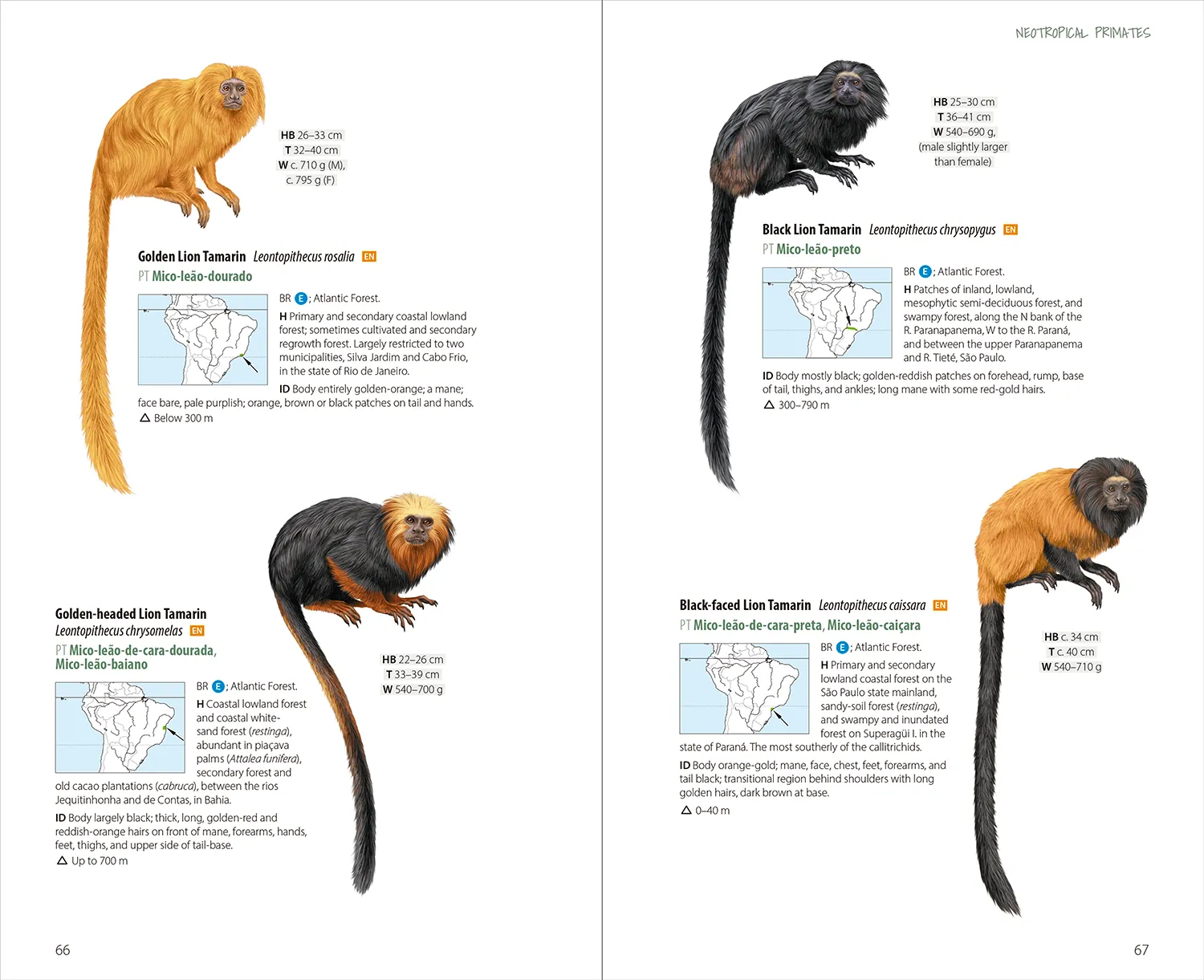

Esta guía describe e ilustra las especies y subespecies de primates de América del Sur, América Central y México. Esta región tiene el mayor número de taxones de primates en comparación con cualquier otra región importante en la que se encuentran primates, con un total de 217 especies y subespecies en 24 géneros y cinco familias.

Con un formato fácil de usar y muy práctico para el campo, este nuevo libro permite a los visitantes ver de un vistazo qué especies están presentes en los 21 países de la región neotropical que tienen poblaciones silvestres de primates, y ofrece indicaciones que ayudarán en su identificación.

La guía abarca todas las especies y subespecies de primates que se encuentran de manera natural en los Neotrópicos, así como tres especies africanas que han sido introducidas y que ahora son asilvestradas en algunas islas del Caribe, incluyendo Barbados, San Cristóbal y Nieves, Santa Lucía, Granada, Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten y Anguila.

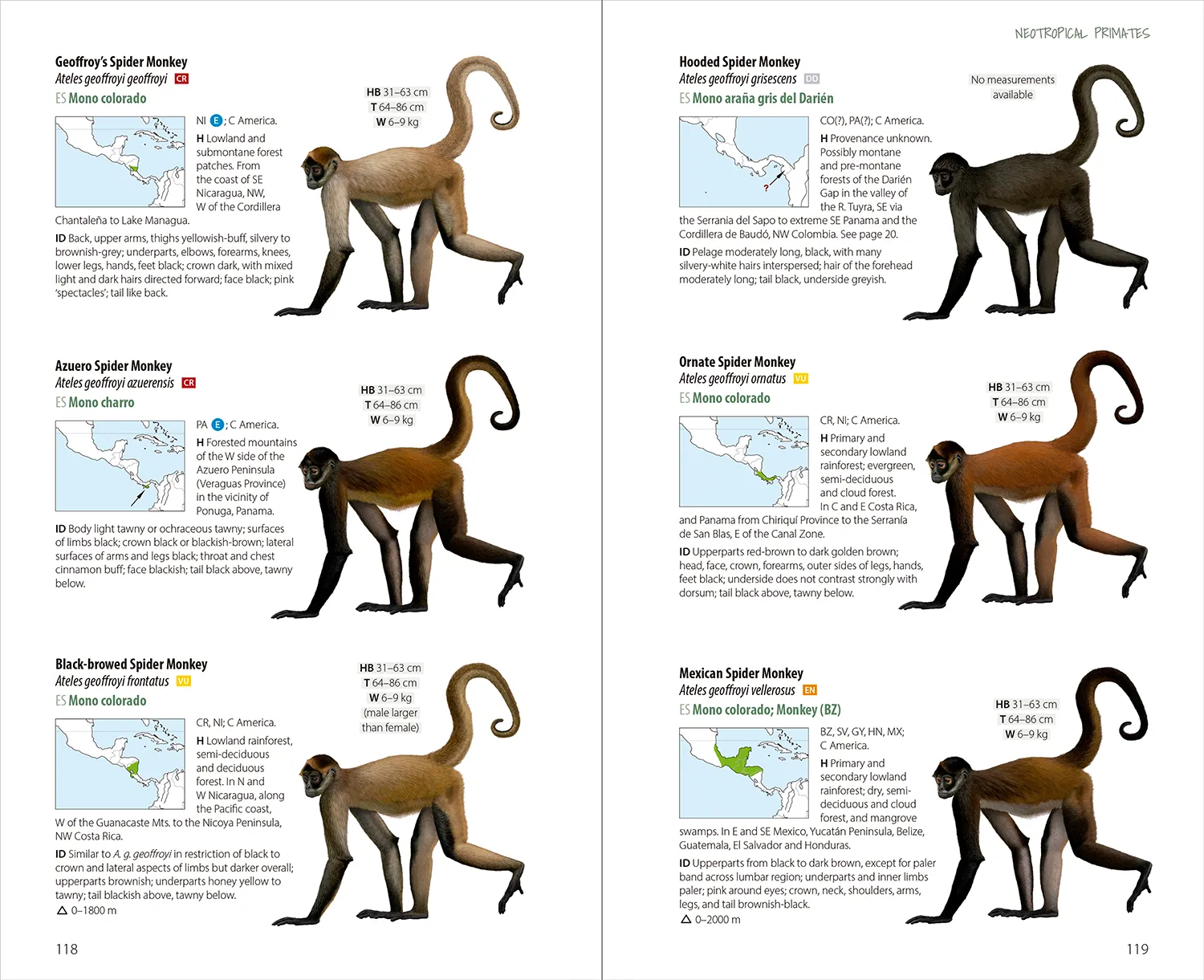

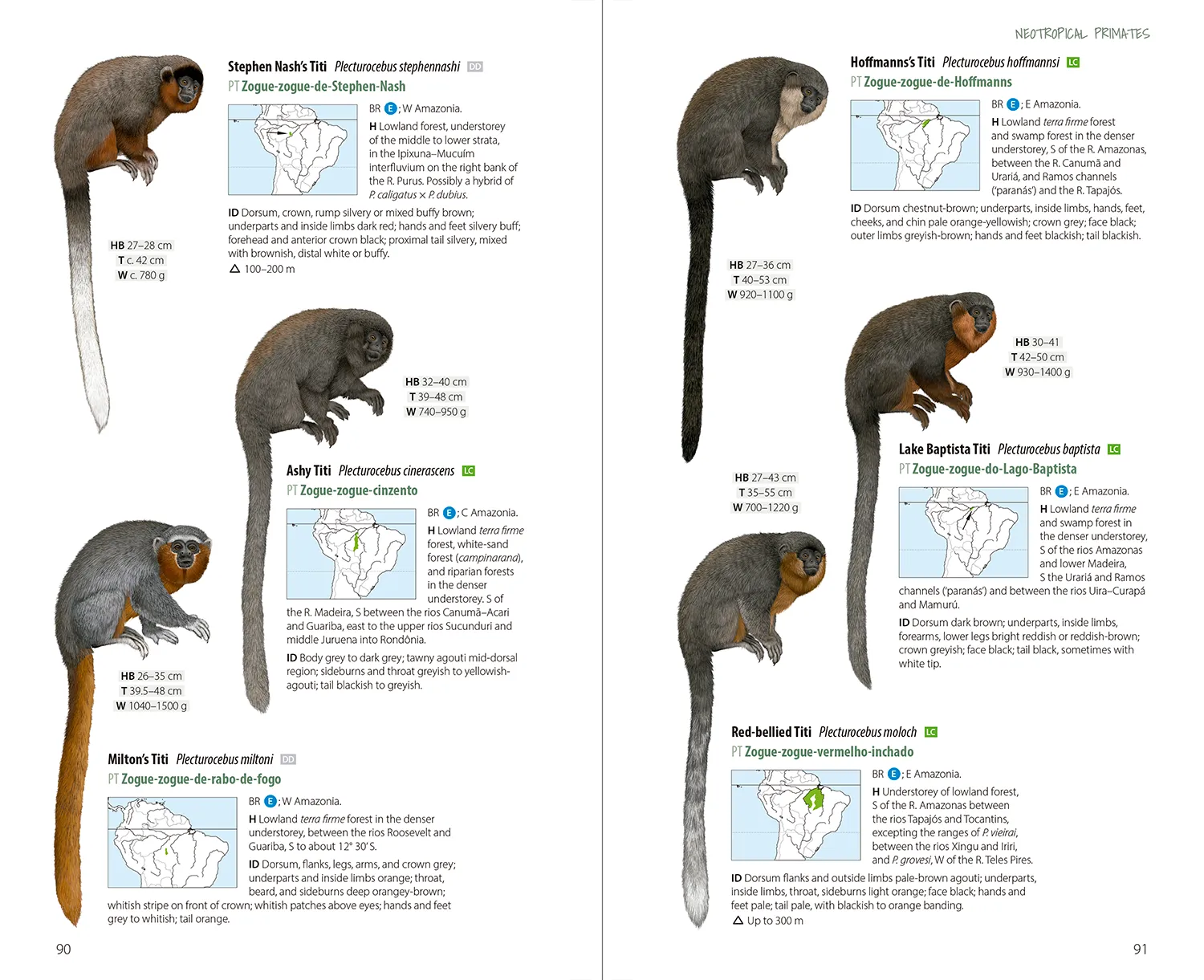

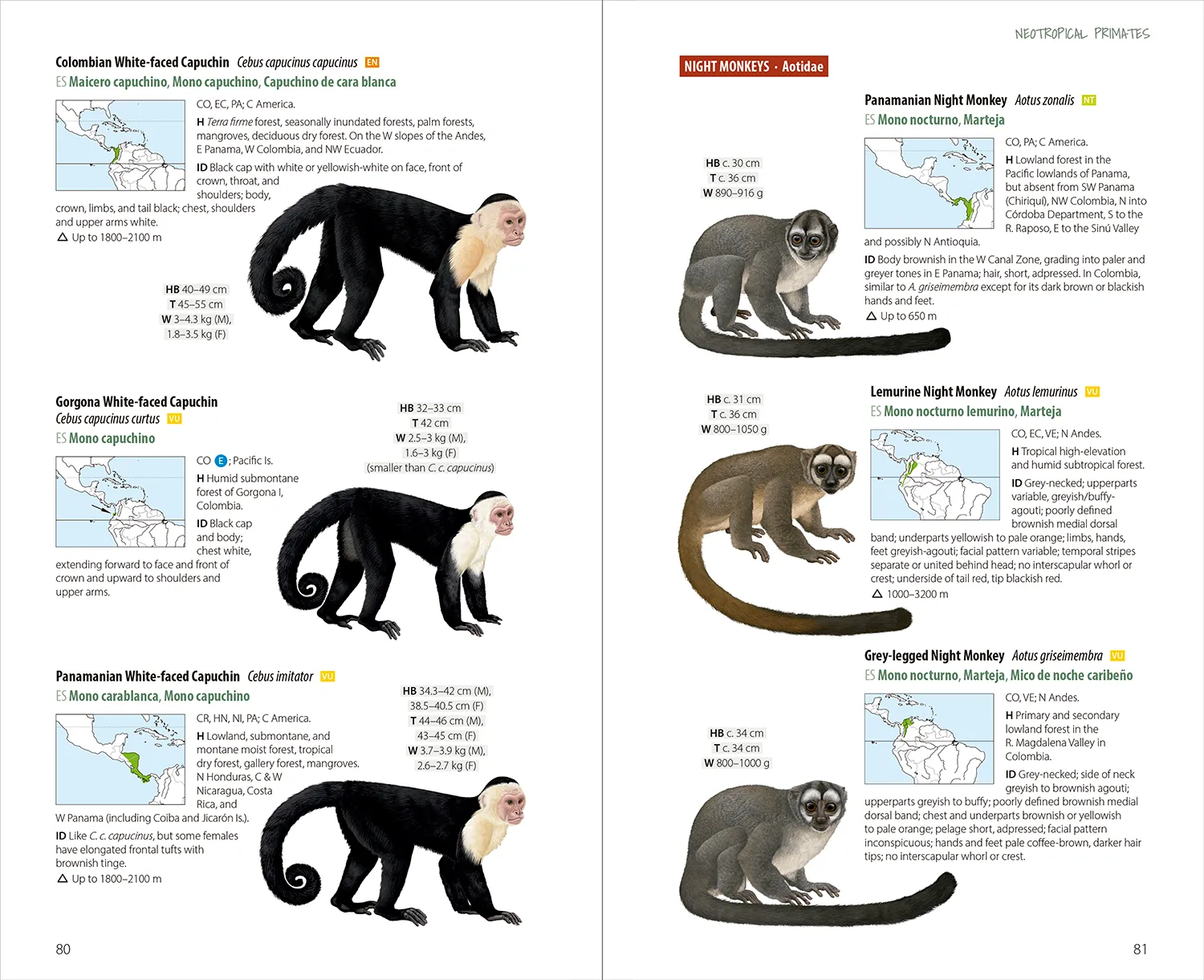

Los textos para cada especie incluyen nombres científicos, nombres comunes en inglés, nombres adicionales en portugués y español, así como en francés para las especies presentes en la Guayana Francesa y en sranan tongo para aquellas en Surinam. También se incluye el estado de conservación según la Lista Roja de Especies Amenazadas de la UICN, los detalles más relevantes sobre hábitats y distribución geográfica, breves notas descriptivas y, cuando está disponible, el rango altitudinal.

Cada ficha de especie va acompañada de una o más ilustraciones y un mapa de distribución.

Para estimular la observación de primates y la creación de listas de vida de primates, se proporciona una lista de verificación completa con los nombres comunes y los países donde se encuentran las diferentes especies, para que puedas marcar los primates que has visto en tu propia lista de vida.

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne –

Alfred Russell Wallace who is considered the father of biogeography observed that in South America primates on one side of a river are often different to those on the other side. This is because rivers act as barriers for dispersal and influence speciation over time. A glance through the distribution maps of various primate species in this book illustrates this point very well. What also comes across is that many primate species are restricted to relatively narrow ranges. In South America, there are national parks which are bigger than some of the smaller European countries. Therefore, the absolute size of the range does not always make the problem immediately obvious. However, when looking at the distribution maps it becomes immediately clear that for many species their range on a relative basis, is tiny relative to the size of the neotropics. Relatively speaking, some primate distributions are just a tiny dot in the maps in the book. The ecological and historical biogeographical factors that have led to such reduced relative ranges for primates in many cases also apply more widely to other species of plants and animals as well. The huge number of species in in the neotropics can mask the fact that many species have relatively small ranges. There is a myriad of habitats in the neotropics, differing subtly from one another. As primates are an iconic group of mammals this book serves well to drive home that neotropical forests are not one vast homogenous block but with wide variations in their structure and species composition. Holding onto every significant patch of forest that is still left is important because there are subtle differences in the ecology of these forests and there can be many species that are confined to the surviving forest fragments.

This book treats a total of 192 species of primates in 5 families and 24 genera as being found in the neotropics. The introduction defines the neotropical region with maps showing the countries in scope. The 21 neotropical countries with primates are listed in a table, ranked by the number of species. In my book collection is a copy of ‘Primate Geography: Progress and Prospects’ published in 2006 by Springer. In it is a paper, ‘Biogeography and Primates: A Review’ by Shawn M. Lehman and John G. Fleagle where the number of primates in the neotropics is stated to be 116. During the intervening 19 years between these publications the number of described species has increased by a staggering 65 per cent. Some of the increase in species is due to splits rather than the discovery of a completely hitherto unknown primate species. But this nevertheless reinforces the need to conserve what is left as disjunct populations may over time come to be recognised as distinct species.

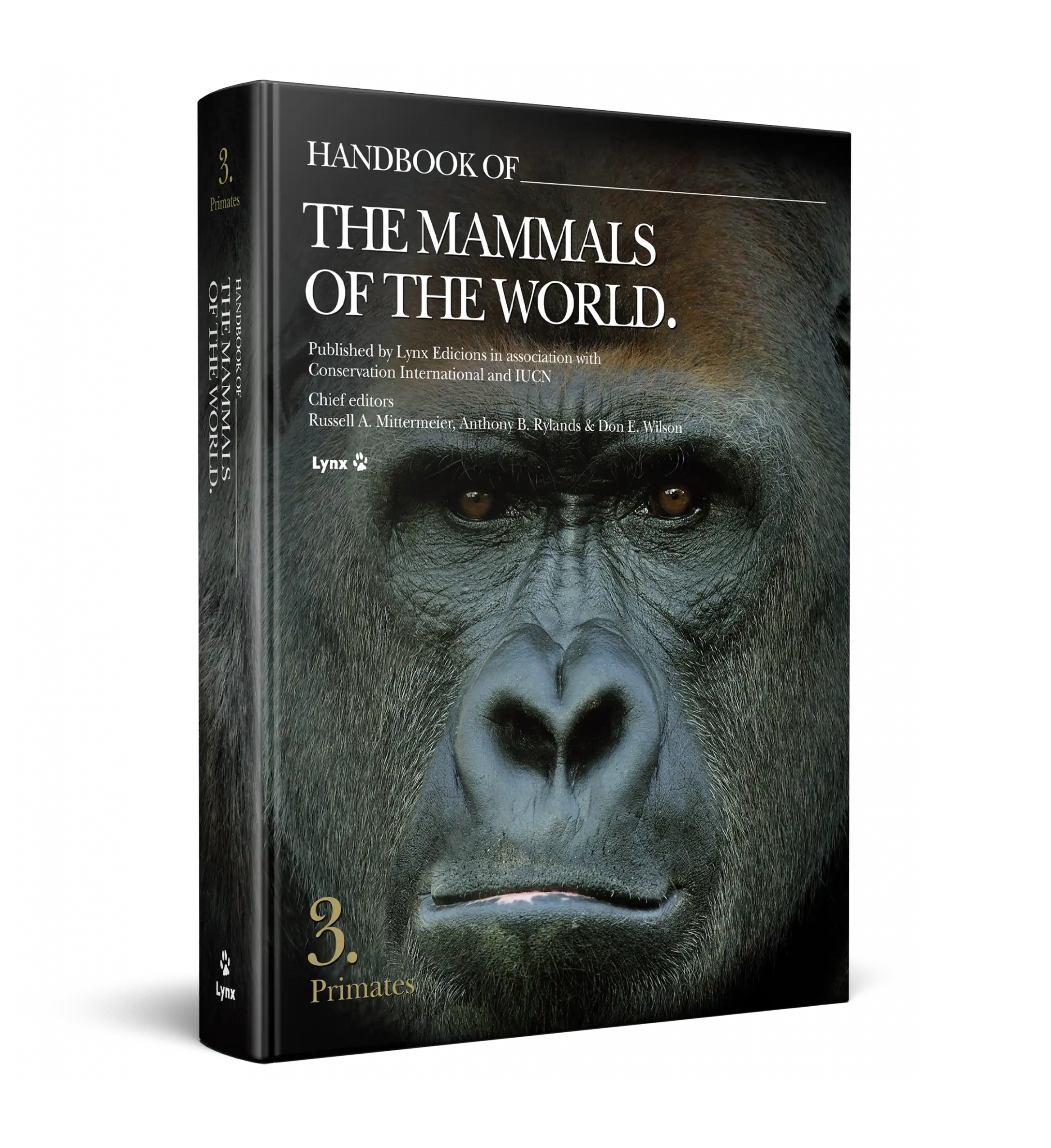

To me therefore, this book is something more than an illustrated checklist of primates. It is a compact and beautiful illustration of the diversity of species in the neotropics, how fragile their continued existence is, how much more there is to be discovered and a powerful reminder that the neotropical forests are not covered in homogenous forests that are the same everywhere. The checklist is a spin off from the 9 volume series of the Handbook of the Mammals of the World published by Lynx Nature Books. The checklist has 13 authors which is a roll call of some of the leading contemporary primatologists. The illustrated species accounts (pages 46 to 125) form the core of the 141 page book. Each primate species is illustrated with one image with an accompanying distribution map and brief text on habitat and distribution. Additional information includes identification and measurements (head and body length, tail length and weight), names in Portuguese and Spanish, IUCN conservation status and the two letter ISO country code for the countries it is found in. Species endemic to a country are labelled with an ‘E’.

I can see people thumbing through the plates and being inspired to go out and seem some of these remarkable primates. The illustrated checklist is good enough to function as an identification guide and as a life list, as the authors appear to wish and they have devoted a chapter to primate watching and primate tourism.

There is quite a lot packed into this book. To keep the book compact and lightweight, this does mean the choice of font has drifted towards the smaller end of the publishing spectrum. The introductory sections (pages 13 to 44) introduce the neotropical region and neotropical primates. There are country league tables of primates for the world and the neotropics. Brazil, the fifth largest country in the world with large tracts of Amazonia within it, not surprisingly leads in first place in the world with a whopping 145 species. A section on diversity, discusses the families and their genera and species. There are 4 maps. I wish the map on South American rivers was much bigger and had stretched across two pages because the rivers are quite key to pinpointing the locations of many species. The habitats are described under 7 major groups. Under the grouping for Amazonia, 20 different forest types are described. Threats, conservation status, primate watching and primate tourism are the other chapter headings followed by an extensive list of references. The end sections include a checklist of neotropical primates and an index.

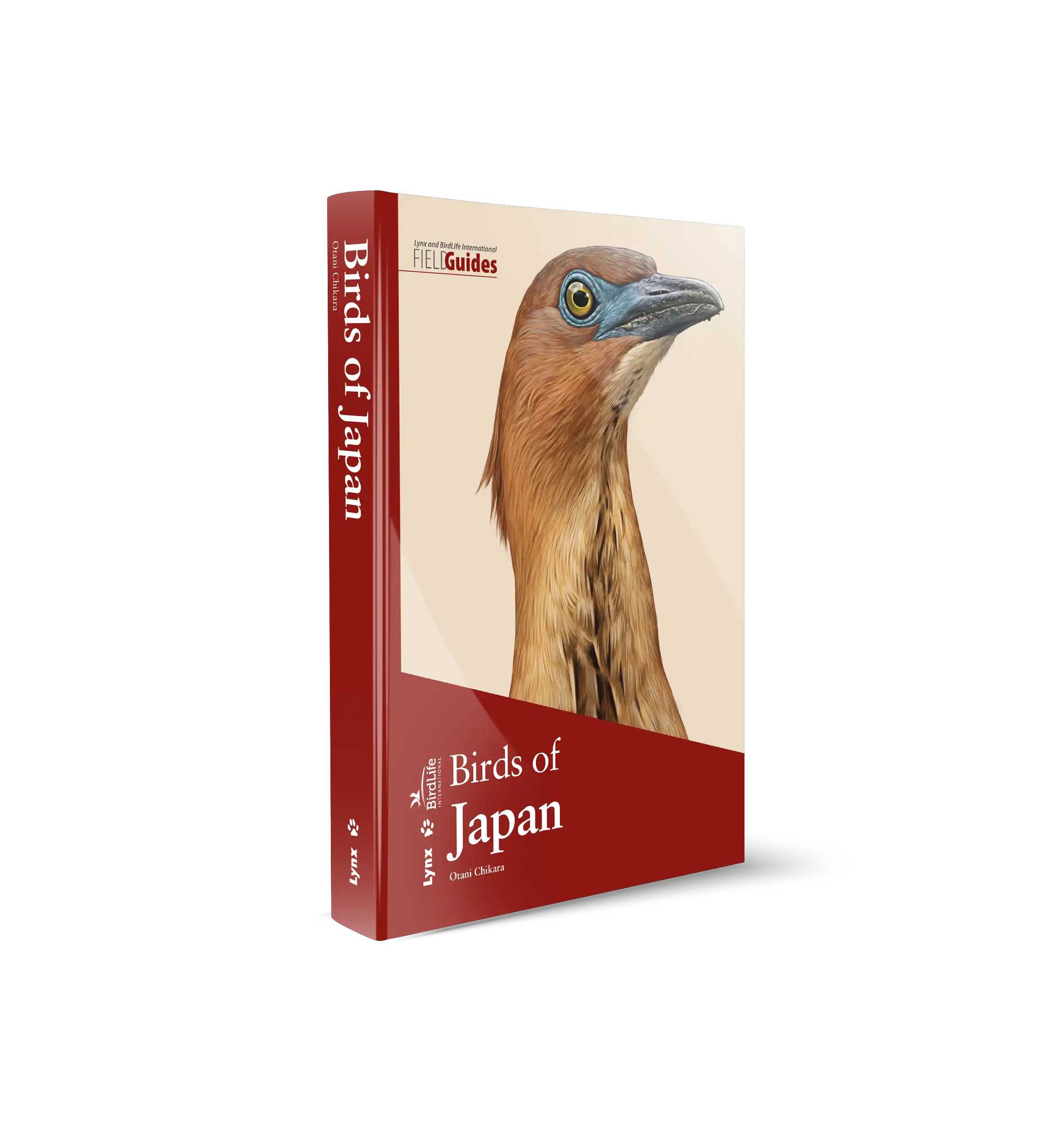

I received this book a few weeks after a trip to Peru where I had spent 5 days in the Amazon at the Inkaterra Reserva Amazonica Lodge. I had arrived with the splendid Helm Field Guide to the Birds of Peru by Thomas S. Schulenberg et. al. (Princeton University Press) and for background reading John Kricher’s wonderful ‘A Neotropical Companion (Princeton University Press). A field guide to the mammals of Peru was not available and I was not sure which species exactly I had seen of the Squirrell Monkey or Saddleback Tamarin. To my surprise, searching on the internet produced very little information on the exact primate species, and the various AI search engines including Google AI and ChatGPT also failed miserably because they can only abstract what has been posted out there. Hopefully, there are enough customers out there for Lynx Nature books to consider publishing some mammals field guides to the more heavily visited countries in South America in the way they have spun off country field guides for birds from their landmark Handbook of the Birds of the World. However, with a mammal field guide, to keep it compact and aimed at the general enthusiast there is case that with certain families such as murids (rats and mice) and shrews and wider groups such as the bats (comprised of several mammal families), there may be a case for restricting the species to the common species of urban habitats and just a few representative examples from families and genera.

Although not described as a field guide, it is the closest book available to concise field guide for neotropical primates. I used the illustrated checklist’s illustrations and text and most importantly the distribution maps to narrow down the species I had seen in Peru. Although my images of the Saddle-back Tamarin did not correspond closely with the illustration, my best ID effort of the species I had seen in Amazonia (during five days) around the Inkaterra Reserva Amazonica lodge were Large-headed Capuchin (Sapajus macrocephalus), Bolivian Red Howler Monkey (Alouatta sara), Peruvian Squirrell Monkey (Saimiri boliviensis peruviensis) and Weddell’s Saddle-back Tamarin (Leontocebus weddelli). I loved my time in the Amazon watching primates and it was very special to watch Saddle-back Tamarins foraging watched only by me and my guide Pedro from the lodge. According to the country league table in the book, Peru comes fifth in the world and second in the neotropics with 58 species. With a country like Peru, it will require a vast amount of time and vast distances to be covered to see a significant proportion of the primate species it holds.

This illustrated checklist should make it easier for people who live in the neotropics to appreciate the richness of species they have of these iconic mammals and hopefully inspire even more people to take more action to conserve habitats for primate.