Latests posts

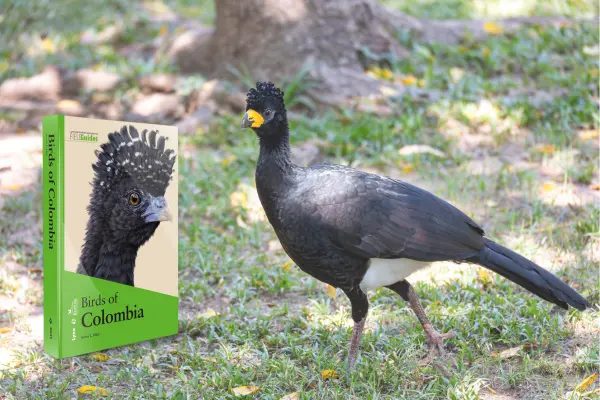

Birds of Colombia: A Journey Through the World’s Most Bird-Rich Nation

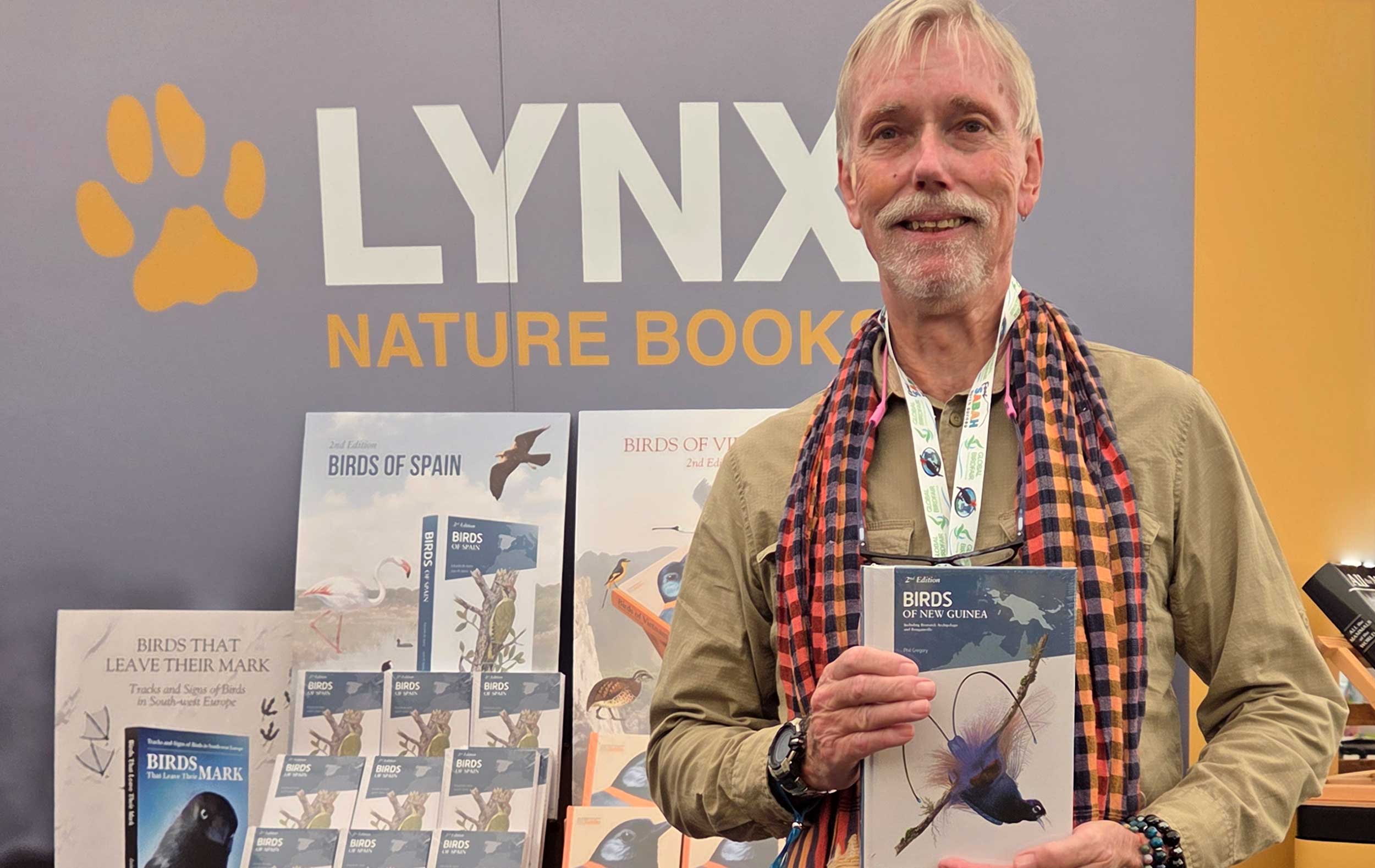

Birds of paradise and beyond: the new edition of Birds of New Guinea

Birdwatching in Spain: a guide to species, habitats and the joy of birding

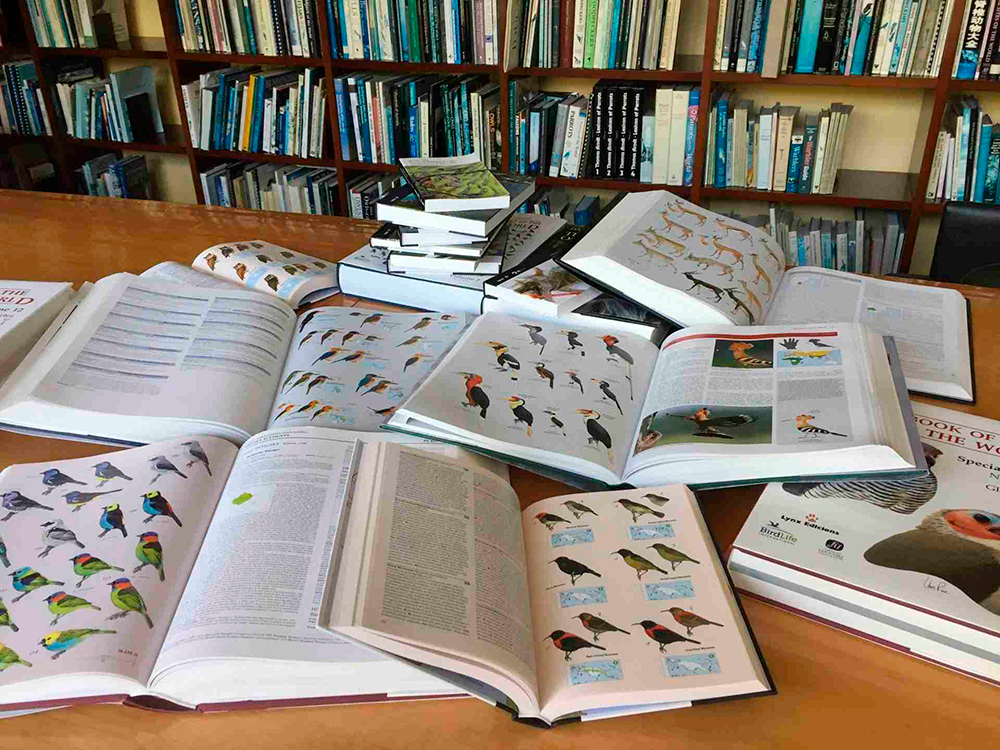

Why books matter for nature: the role of scientific publishing in conservation

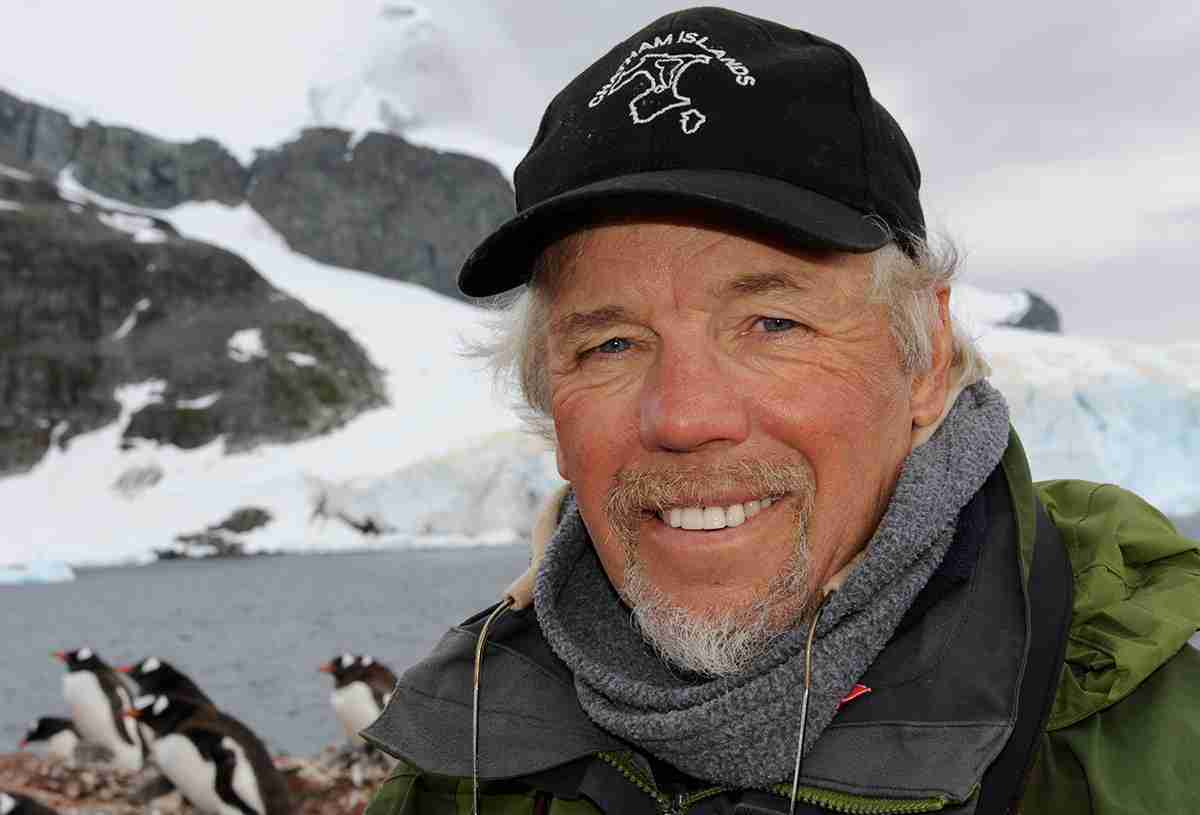

Seabirder, author and artist Peter Harrison discusses “SEABIRDS: The New Identification Guide”

Once bitten, twice shy: between the covers of the second edition of the Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago

Taming the wild world of mammalian taxonomy with Connor Burgin

Discover the birds of Malaysia with Chong Leong Puan

Vietnam’s birds revisited: an interview with Richard Craik on the new edition of Birds of Vietnam

When Birds of Vietnam was first published in 2018, it filled a long-standing gap for birders in Southeast Asia. For the first time, those exploring Vietnam’s forests, wetlands and coastlines had a dedicated field guide covering the country’s remarkably rich birdlife. The book, coauthored by Vietnam birding pioneers Richard Craik and Le Quy Minh, quickly became the go-to resource for both local and visiting birdwatchers.

Now, just six years later, a new edition of Birds of Vietnam has been released. And it’s not just a reprint. With 13 new species added to the country list and significant updates to maps and taxonomy, the second edition reflects how quickly the understanding of Vietnam’s birdlife is evolving, alongside growing interest in birding and research in the region.

We caught up with Richard Craik to find out what’s new in the book, what’s changed in the field, and what birders need to know when visiting Vietnam today.

Why a second edition, and why now?

With the first edition of the field guide sold out, we had to make a decision: reprint the original book or produce a fully updated second edition. As 13 new bird species had been added to the Vietnam country list in the intervening years, the decision was an easy one and we quickly set to work on a thoroughly revised and updated second edition.

This edition includes 13 newly observed bird species in Vietnam since 2018. Can you share a few of these exciting additions and where keen birders have the best chance of finding them?

All 13 new additions to the Vietnam country list are classified as “vagrants”, so there is always the possibility they could turn up in similar locations again, but at the current time these are the first and only records from Vietnam for these species.

The list of new species includes three offshore or coastal vagrants from southern Vietnam—Red-footed Booby, Long-tailed Jaeger and Pomarine Jaeger—as well as a species of wildfowl, Baikal Teal, a pigeon, a cuckoo and a snipe, all recorded from northern Vietnam. The remaining new species are two previously unrecorded starlings, a thrush, a pipit, a finch and a bunting.

📷 One of the species newly recorded in Vietnam since 2018: the Brown-headed Thrush.

With 16 endemic species/subspecies groups and 42 near-endemic ones, Vietnam has one of the richest avifaunas in mainland Southeast Asia. In your experience, which of these birds are the most challenging to find in the wild, and why?

Many of Vietnam’s endemic and near-endemic species can be located with some prior research into their range, habitat and seasonal patterns, all of which can be found in the species texts of the field guide. Several species, however, present more of a challenge.

Among these are White-throated Wren-babbler and Nonggang Babbler, two rare and highly localised residents found only in remote, rugged habitats of northern Vietnam. Another is the critically endangered Vietnam Pheasant, an endemic species that inhabits the dense bamboo and rattan understorey of secondary evergreen forests in northern Central Vietnam. With very few records in the past half-century, this species may well be on the brink of extinction in the wild.

Fortunately, the Vietnam Pheasant, or Edwards’s Pheasant as it was formerly known, breeds well in captivity, offering hope for potential reintroduction into protected areas of its former range in the future.

📷 The Vietnam Pheasant, feared close to extinction in the wild, thrives in captivity, raising the hope of a future reintroduction.

The new edition also features improved distribution maps. Were there any surprises in how certain species’ ranges have shifted in recent years?

With a growing number of visiting and resident birders recording sightings over the past two decades, our understanding of Vietnam’s birds’ distribution continues to improve. While inevitably some species’ ranges are shrinking due to habitat loss driven by Vietnam’s expanding population, with more birders out there, other species are being reported from areas where they were previously unrecorded.

This shift is reflected in the updated distribution maps included in the second edition of Birds of Vietnam. Meanwhile, two species unknown from Vietnam just 20 years ago—Indian Sparrow (the local subspecies of House Sparrow) and Zebra Dove—have been rapidly colonising the country from south to north. Today, these two species are among the most common urban birds in many parts of southern and central Vietnam.

Conservation remains a critical issue for Vietnam’s birds. Since publishing the first edition, have you observed any positive changes or worrying trends in Vietnam’s bird populations and habitats? What should visiting birders keep in mind to be responsible birdwatchers?

On the positive side, there is a growing awareness among the younger generation of the need to conserve Vietnam’s vanishing wildlife and preserve its natural habitats. However, the consumption of wildlife and wildlife products persists among the older generation, as does the tradition of keeping wild-caught birds in cages.

For us, the most concerning trend among birders in Vietnam is the shift in recent years from traditional birdwatching to bird photography. While bird photography may seem harmless enough, it becomes a serious issue when the pursuit of the perfect image takes priority over the well-being of the birds and their habitat.

In Vietnam, as in much of Southeast Asia, bird photography usually involves sitting in hides or blinds while birds are lured into a cleared patch of forest with mealworms and recordings of their calls. Not only does this disturb the birds and alter their natural behaviours, it also creates a dependency on artificial food sources. In some species it can even lead to physical changes. For example, green magpies, whose vibrant green plumage fades to pale blue when fed an unnatural diet of mealworms over an extended period of time.

📷 The critically endangered, endemic Orange-breasted Laughingthrush has disappeared from many of its former locations due to trapping at photographic hides.

As if this isn’t already enough, bird photography from hides and baiting stations in Vietnam comes with an additional problem. Once the photographers and hide owners have packed up and gone home, the trappers move in with mealworms and bird recordings, and the birds are easily caught—destined for the cage bird trade. The use of hides and baiting stations by bird photographers in Vietnam has already led to the local extirpation of several rare species, most notably the endemic Orange-breasted Laughingthrush, which has completely disappeared from many of its known sites on the Dalat Plateau in recent years.

📷 The illegal bird trade remains a serious threat to Vietnam’s endemic species, like this Collared Laughingthrush.

What do you hope the new edition of Birds of Vietnam will bring to birders visiting Vietnam today?

More people are birding than ever. With better awareness and responsible practices, we can help protect Vietnam’s unique birds for generations to come. Our hope is that this updated edition of Birds of Vietnam will continue to serve as a trusted resource for birders, scientists, students, and anyone with an interest in Vietnam’s birds, fostering a deeper appreciation and understanding of this country’s remarkable avifauna.

The second edition of Birds of Vietnam is now available through the Lynx Nature Books website. Whether you’re planning your first birding trip to Vietnam or returning to familiar trails, this new edition offers an invaluable, updated companion to one of Asia’s richest birding destinations.

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books