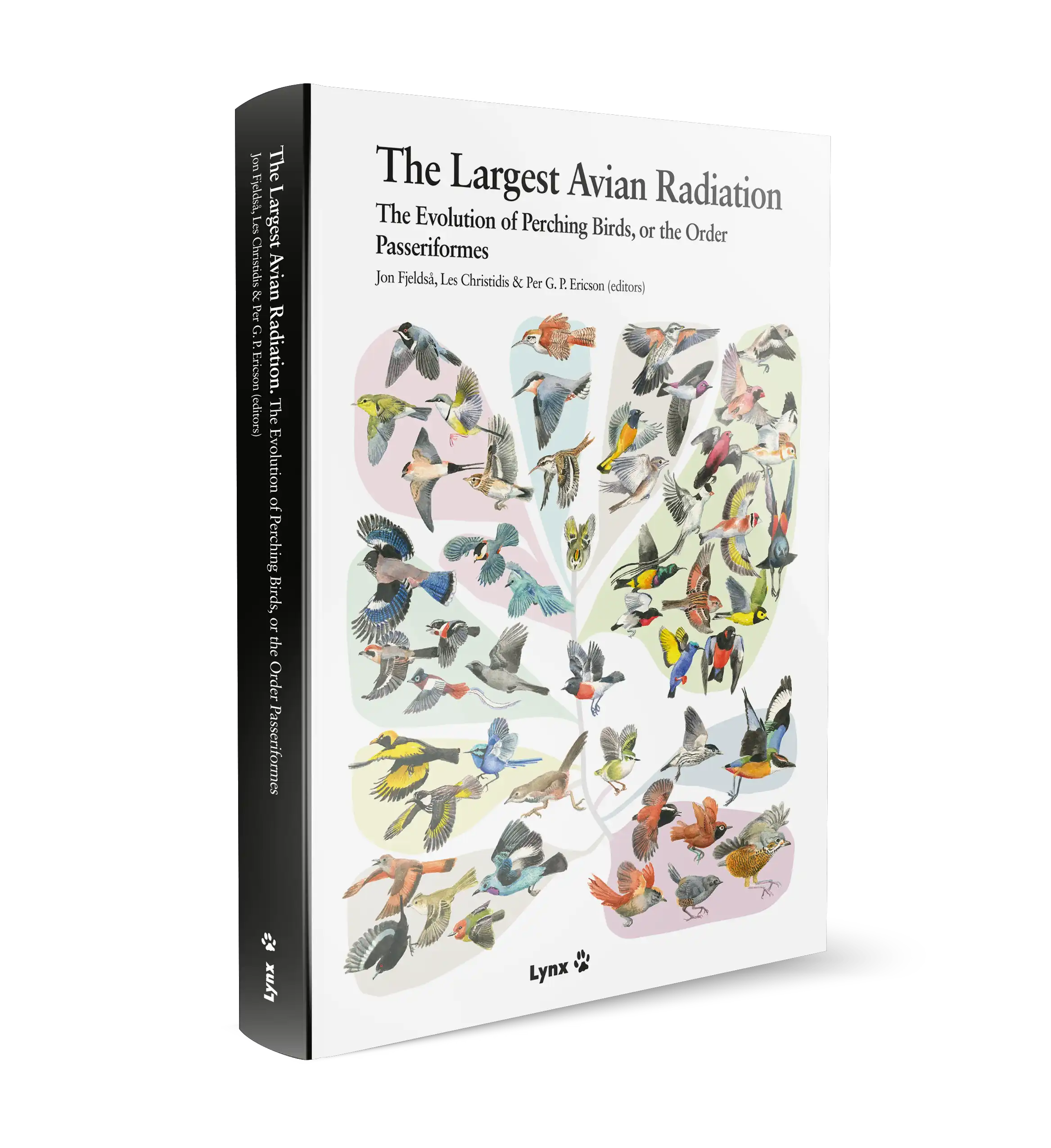

The Largest Avian RadiationThe Evolution of Perching Birds, or the Order Passeriformes

Original price was: $108.80.$97.92Current price is: $97.92.

In stock

Original price was: $108.80.$97.92Current price is: $97.92.

Weight

2.6 kg

Size

24 × 31 cm

Language

English

Format

Hardback

Pages

445

Publishing date

November 2020

Published by

Lynx Edicions

Description

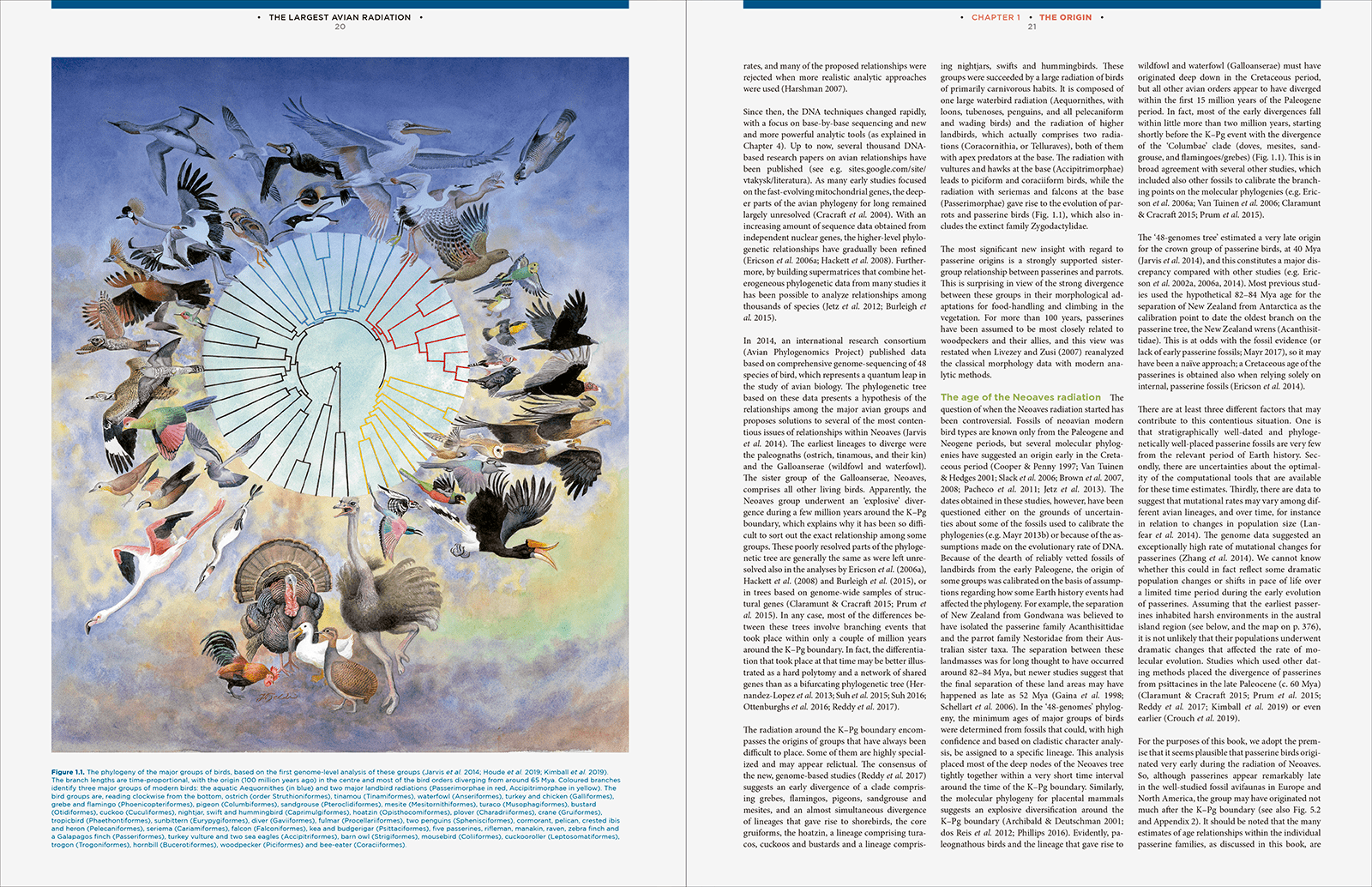

With more than 6200 species, the perching—or passerine—birds represent one of the most remarkably rapid proliferations of species. The traditional classification of birds, which was mainly based on comparative anatomical studies made more than 100 years ago, could do little to resolve the relationships among passerines because they were generally too anatomically uniform. Therefore, the classification that was used for most of the 20th century was a practical arrangement, where the thousands of species were accommodated in a few broad groups based mainly on ecological adaptations.

Recent DNA studies have dramatically changed the understanding of passerine evolutionary relationships. Apparently, the passerines originated during the early radiation of modern birds, on the austral continents (South America, Antarctica and Australia), after a global catastrophe had wiped out most of the ancient terrestrial life, including large dinosaurs and early birds.

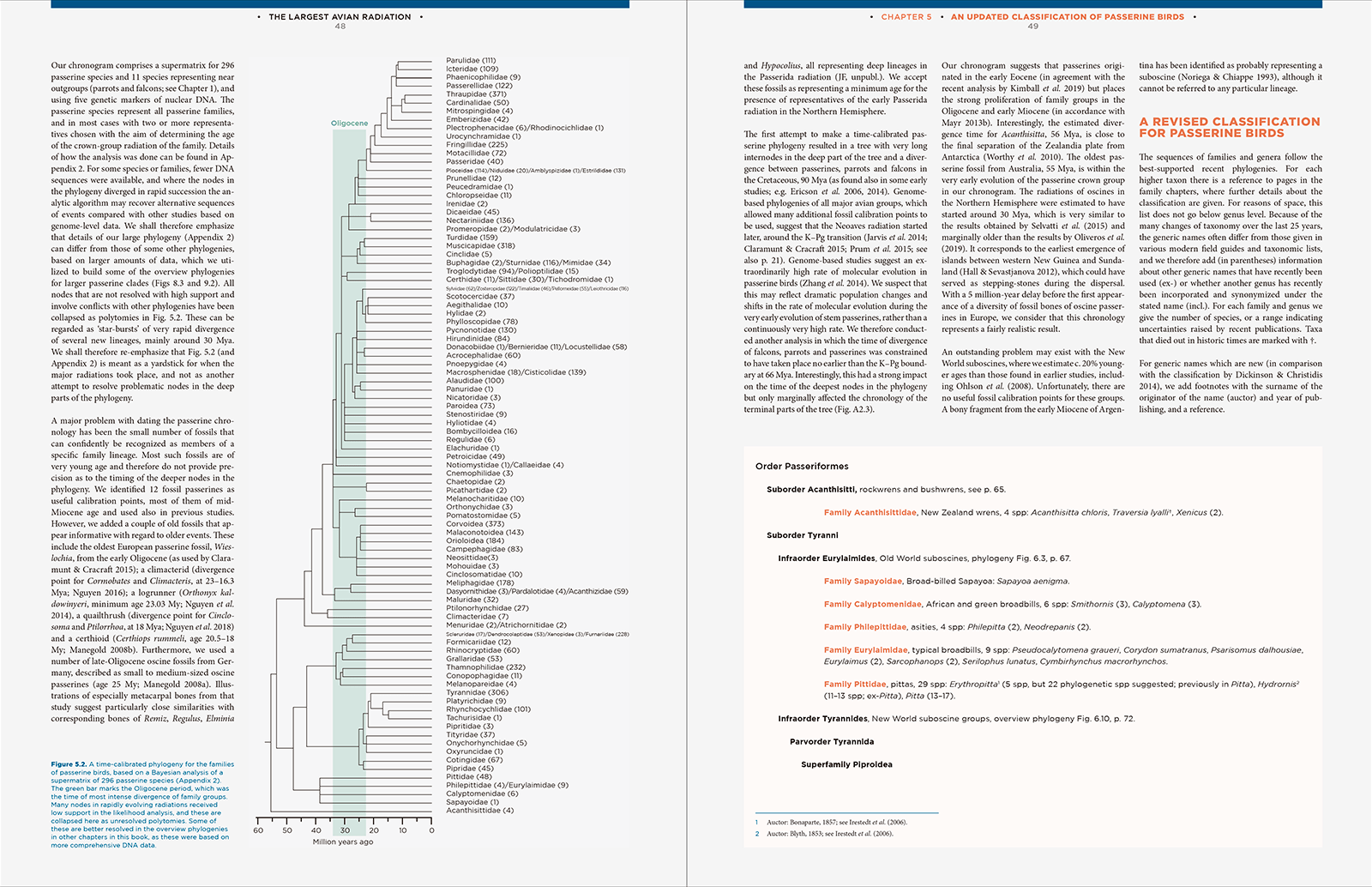

This book reveals the remarkable new history of how passerines diversified and dispersed across the entire world. It also presents and explains the new classification, which reflects the phylogenetic history. The new insights reveal that many of the old evolutionary lineages comprise only a few species that remained in their area of origin or underwent limited dispersal. Only a small number of groups underwent significant proliferation of new species and just five (of 145) passerine families are represented on all continents but Antarctica. Even so, the global variation in species richness generally correlates well with the variation in productivity across different environments. We see how a seemingly constant overall rate of evolution of new species is possible because of rapid proliferation in new ecological niches, including archipelagos, and an extraordinary accumulation of endemic species in certain tropical mountain ranges.

In addition to describing the revised evolutionary history of passerine birds, the authors try to identify adaptational changes, including shifts in life history strategies, that underlie major evolutionary expansions. Their aim is to further the development of a unified theory to explain how the prodigious variation of Earth’s biodiversity is generated.

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne –

This book is an excellent example of how to make deep science less intimidating. I had wondered how Lynx Edicions that had carved a niche for being at the interface between hard science and popular natural history would tackle a subject that would appear to most people to be dense and impenetrable. Superb design and excellent writing and editing have resulted in a book which not only keen birders but others interested in topics such as speciation and biogeography would find interesting.

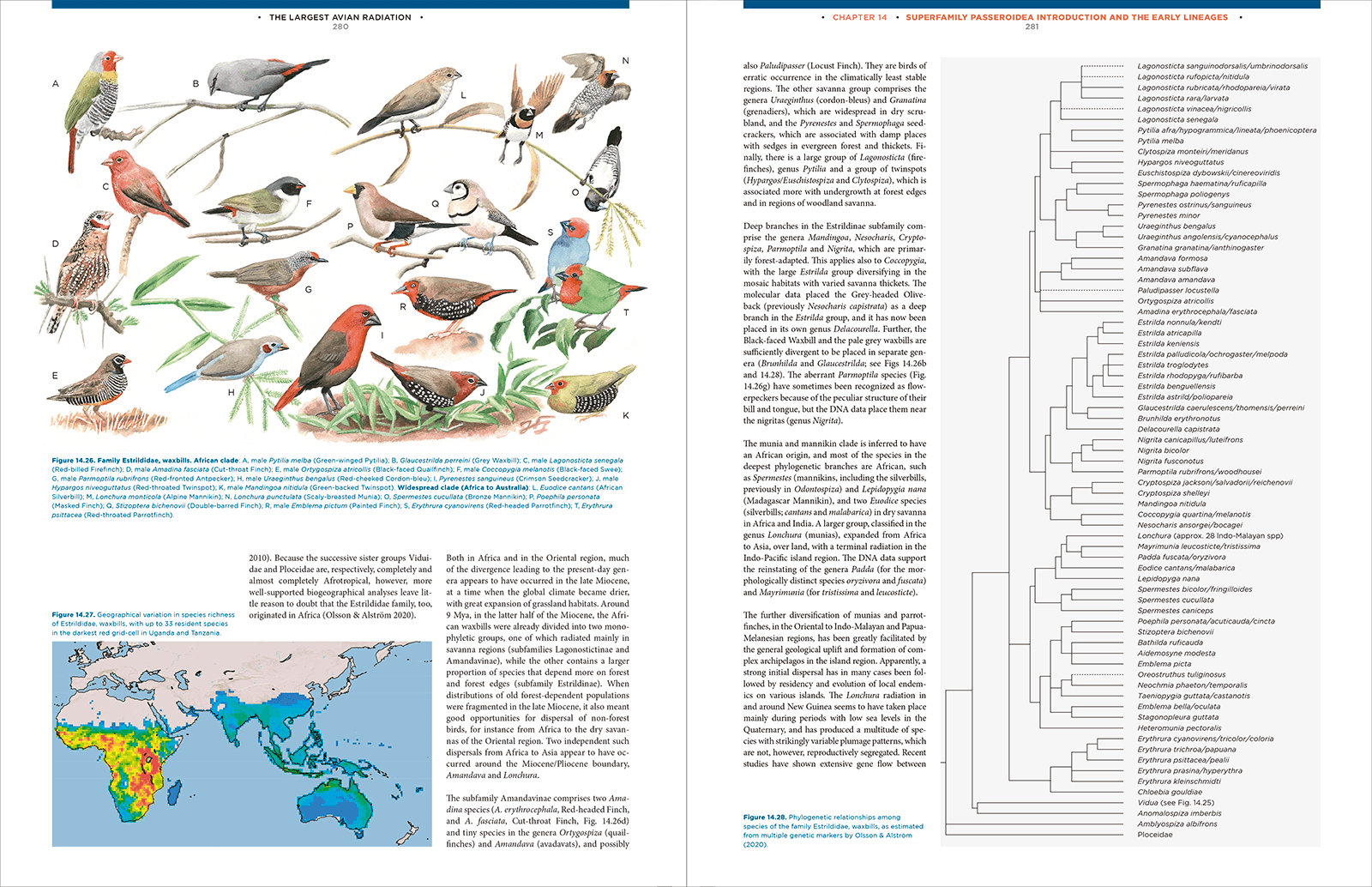

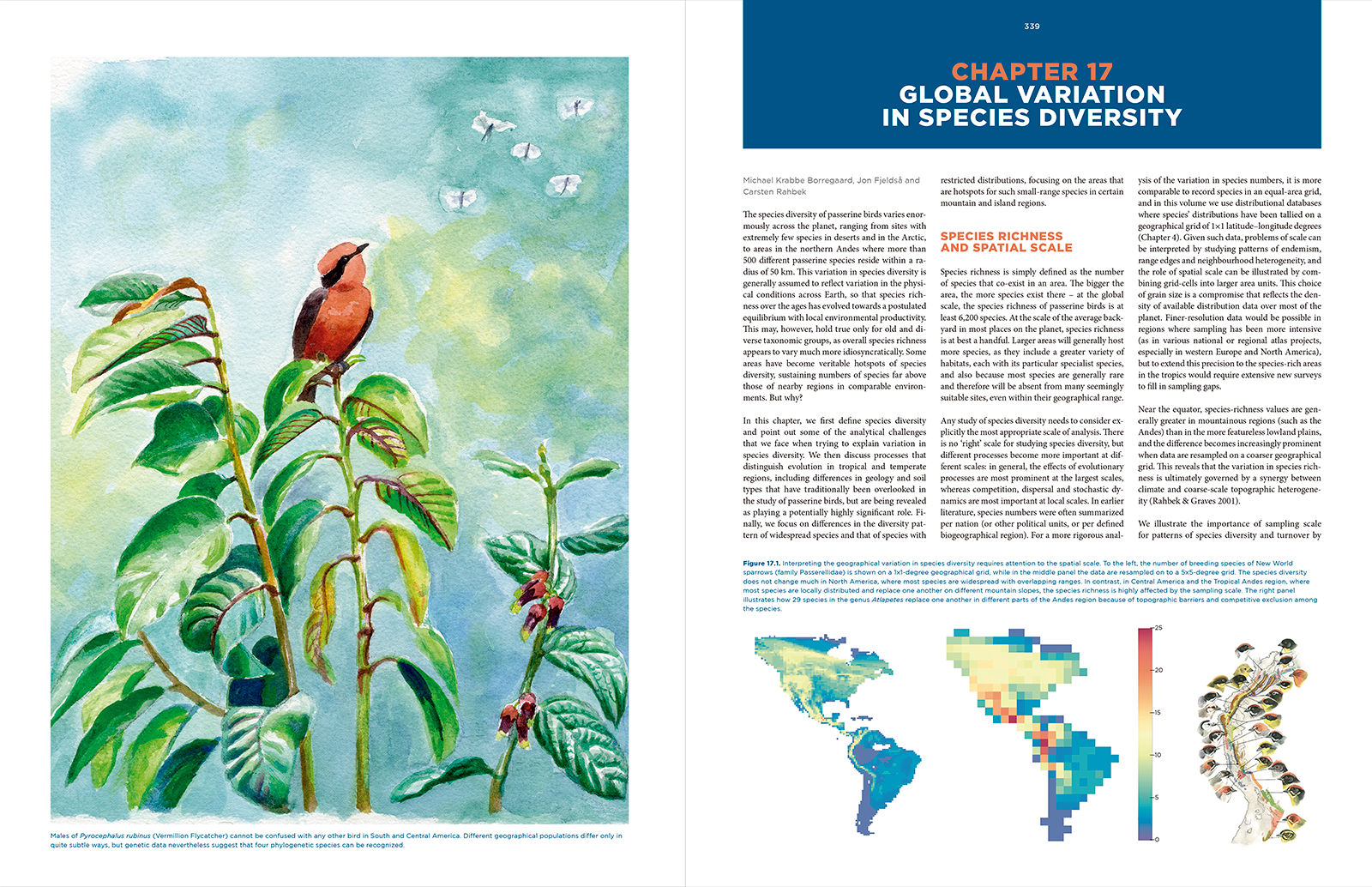

The first thing that strikes you about the book is the design. Chapters and section headings are announced in capital letters in bright colours. There is generous use of delightful bird illustrations (by the multi-talented Jon Fjeldså, the lead editor) which although accurate have a lightness that leans towards arty than illustrative. All of this creates the right ‘mood music’ for anyone who may have been otherwise intimidated by the prospect of delving into the details of molecular phylogenetics.

Over the years, many books, in particular those in the excellent Helm Family Monograph series have included introductory sections or chapters explaining molecular phylogenetics. Many books on birders’ bookshelves also contain the branching diagrams or phylogenetic trees arising from genetic studies. Furthermore, attendees of popular talks at the more serious end of ornithology are also used to discussions on molecular phylogenetics. Technical knowledge in the world of birding has come a long way in the last few decades and I suspect most birders will be comfortable with the vast majority of the text in this book. However, I would caution this is not a book for everyone with an interest in birds. You need to be someone who is already following with interest, the science behind splits and lumps at species level to follow the discussions in this book although the book is focussed at the higher taxonomic levels of families.

The book is in three sections. Most people may find that this book can be approached by reading ‘Section 1 Background’ followed by ‘Section 3. Thematic chapters’. At the core of the book is ‘Section 2. Classification and families of passerine birds’ (pages 45- 318). Section 2 begins with an ‘An Updated Classification of Passerine Birds’ which discusses past attempts to classify the passerines and concludes with a new family tree that shows various higher taxonomic levels including suborders, infraorders, parvorders, superfamilies, subfamilies and families. The design is excellent and uses indentation, boldfacing and colours to help with easy and comfortable visual navigation. Chapters 6 to 14 discuss each family of passerines. The families are grouped in the chapters under higher taxonomic groupings. For example, chapter 8 is titled the ‘Cohort Corvoides: the crow like passerines’. Whether you have a special interest in a family, or doing some background reading in anticipation of seeing new families on a forthcoming birding trip or one of the growing band of birders who are trying to see every bird family, these chapters will be of absorbing interest, provided you are not fazed by a sciencey text. If the presence of bracketed citations and the phylogenetic diagrams are ignored, almost all of the text is readable to a keen birder of the sort who would be subscribing to a journal like ‘British Birds’. Occasionally a family account may have extensive discussion on revisions based on molecular phylogenetics; examples include the sunbirds and tanagers. Admittedly, these can be heavy reading.

Although this is a book on passerine birds, the first four chapters will be useful reading to anyone with an interest in any animal groups, especially vertebrates. There is useful background information here on systematics and taxonomy and forces behind evolutionary change. We also learn of the important role of New Guinea as a staging post for the passerines to spread across the world from an origin in the Southern Hemisphere. ‘Section 3. Thematic chapters’ (pages 319 to 369) and the first of two appendices (on a short earth history) also have useful background information. Chapter 15 on ‘The worldwide variation in biodiversity: some central questions and concepts’ and chapter 16 on ‘How new species evolve’ with their chapter headings, give a clear sign on the many interesting topics that are covered in these chapters. Having lived on islands, discussions on speciation models are of particular interest to me. But even a large continent like Africa has over geological time functioned as a patchwork of ecologically isolated areas or islands which has given rise to a number of endemic animals which are confined to limited areas. Island geography or more generally geographical isolation is not the only factor in speciation and chapter 16 also discusses factors such as song in the speciation process. One thing I would have liked to have seen included is a Geological Time Scale. I printed one off the internet to make it easier for me to follow some of the time scales discussed in various chapters.

The references in the end sections are extensive (pages 397 to 432) and reinforce the point that this book is a synthesis of the work of over a thousand papers published on passerine molecular phylogenetics. But as the editors note, this is only a stock take of work done so far and further advances will arise from whole genome sequencing. The lack of a good fossil record and other issues in constructing a molecular phylogeny means that the exact placement of some avian families is still uncertain. An example being the Kinglets or Crests (family Regulidae). This is a family I am familiar with as its members include the Goldcrest, a bird I encounter in parks with conifers in London. As with many family accounts, there is an evocative introduction to the family followed by the nitty gritty of molecular phylogenetics. In this case the surprising conclusion is that the placement of the family is still unresolved. All birders have their favourite bird families and will find it easy to be absorbed by the family accounts of their favourite families.

On the whole it is a remarkable book for its contribution of deep science and insights made accessible to serious birders through good writing and design. I suspect no other group of biological organisms has a cutting edge science book of this genre devoted to it that is aimed at a popular market. The book also casts a light on birders as being a sociological phenomenon. Birders are an economically very valuable group of hobbyists who number in the several hundred thousand and are a subset of a few million birdwatchers world-wide. They generate millions of dollars in revenue for industry sectors from tourism to publishing. But interestingly, probably no other special interest group of this number of adherents follows the outcomes of cutting edge science with such keen interest.