Weight

3.7 kg

Size

24 × 31 cm

Language

English

Format

Hardback

Pages

600

Publishing date

December 2015

Published by

Lynx Edicions

Description

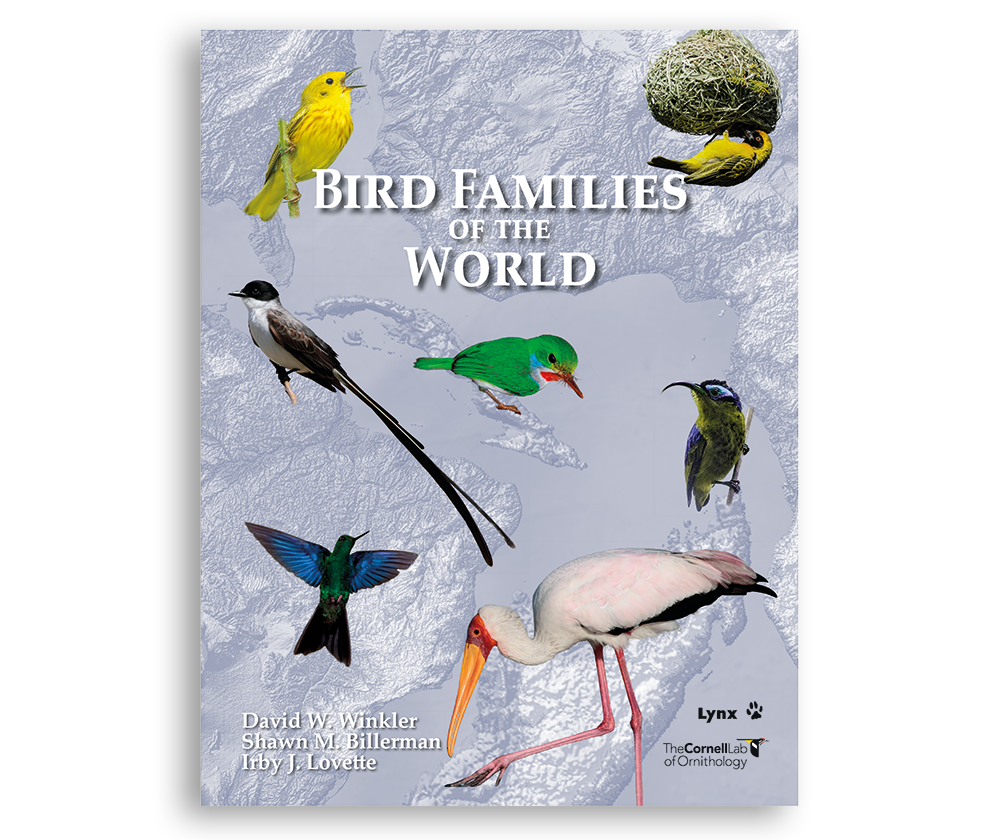

“Memorize all the world’s avian taxonomic families and you’ll enjoy faster bird ids and a global appreciation for bird diversity.” Read David W. Winkler’s complete article 👉 Get to Know Your Bird Families With a New Handbook in the Winter 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

Here in one volume is a synopsis of the diversity of all birds. Published in 2015, between the two volumes of the HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, this volume distills the voluminous detail of the 17-volume Handbook of Birds of the World into a single book. Based on the latest systematic research and summarizing what is known about the life history and biology of each group, this volume will be the best single-volume entry to avian diversity available. Whether you are a birder with an interest in global bird diversity, or a professional ornithologist wishing to update and fill-in your comprehensive knowledge of avian diversity, this volume will be a valuable addition to your library.

An interest in birds is a life-enriching pursuit; the sheer diversity of birds means there are always stunning new species to see and novel facets of their lives to explore. Yet the grand diversity of birds is also a challenge, as it is easy to become disoriented amidst a group that contains more than 10,000 species that vary in nearly all of their most conspicuous attributes. Learning avian diversity requires a mental map to help us organize our experiences and observations. The scientific classification of birds provides exactly this framework, grouping together into Orders and Families birds that are most closely related to one another, and thereby linking species that share distinguishing traits. For those interested in learning about the tremendous diversity of birds world-wide, the best way to start is to learn the families, and this volume is a guide and invitation to do so.

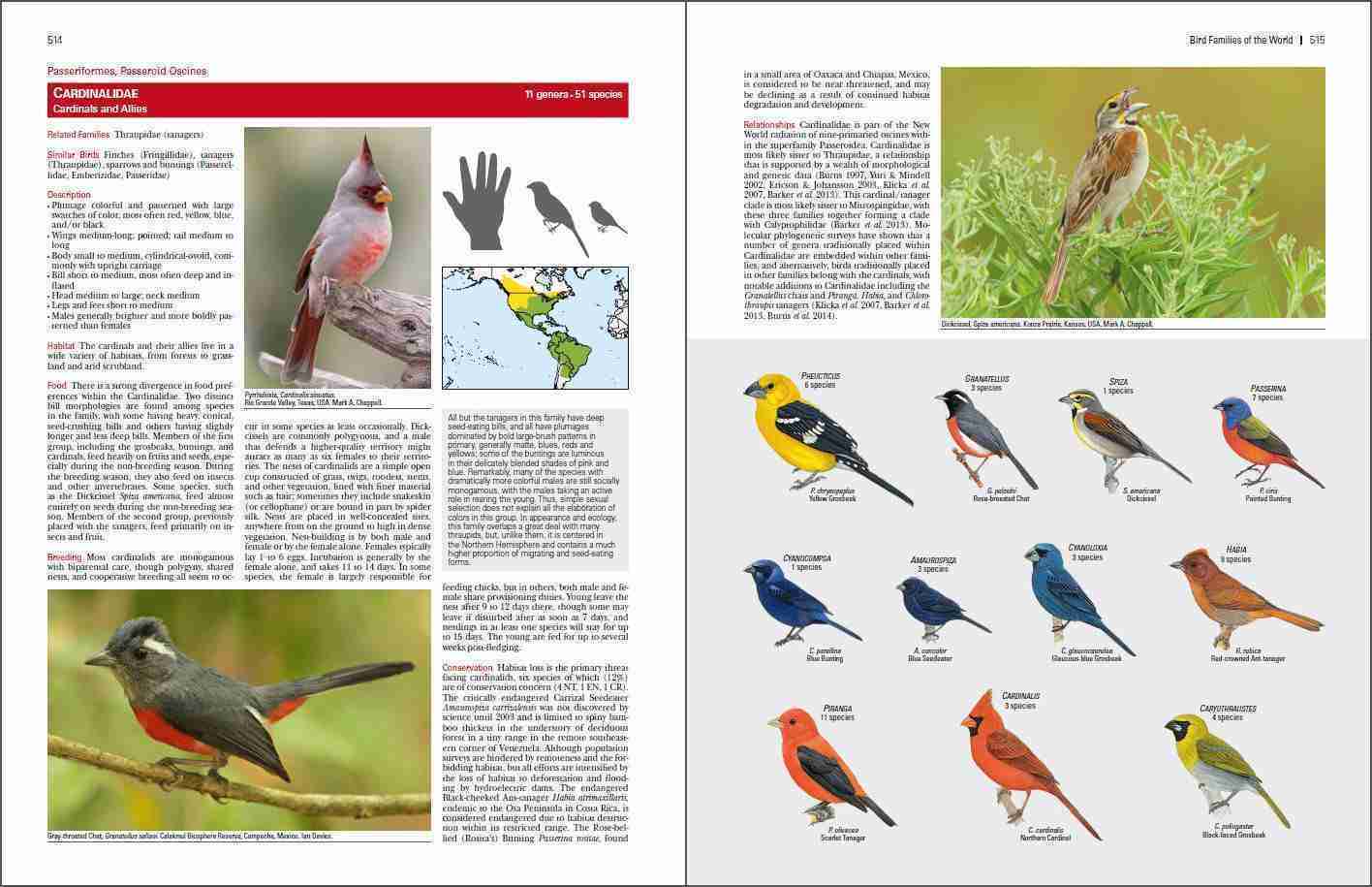

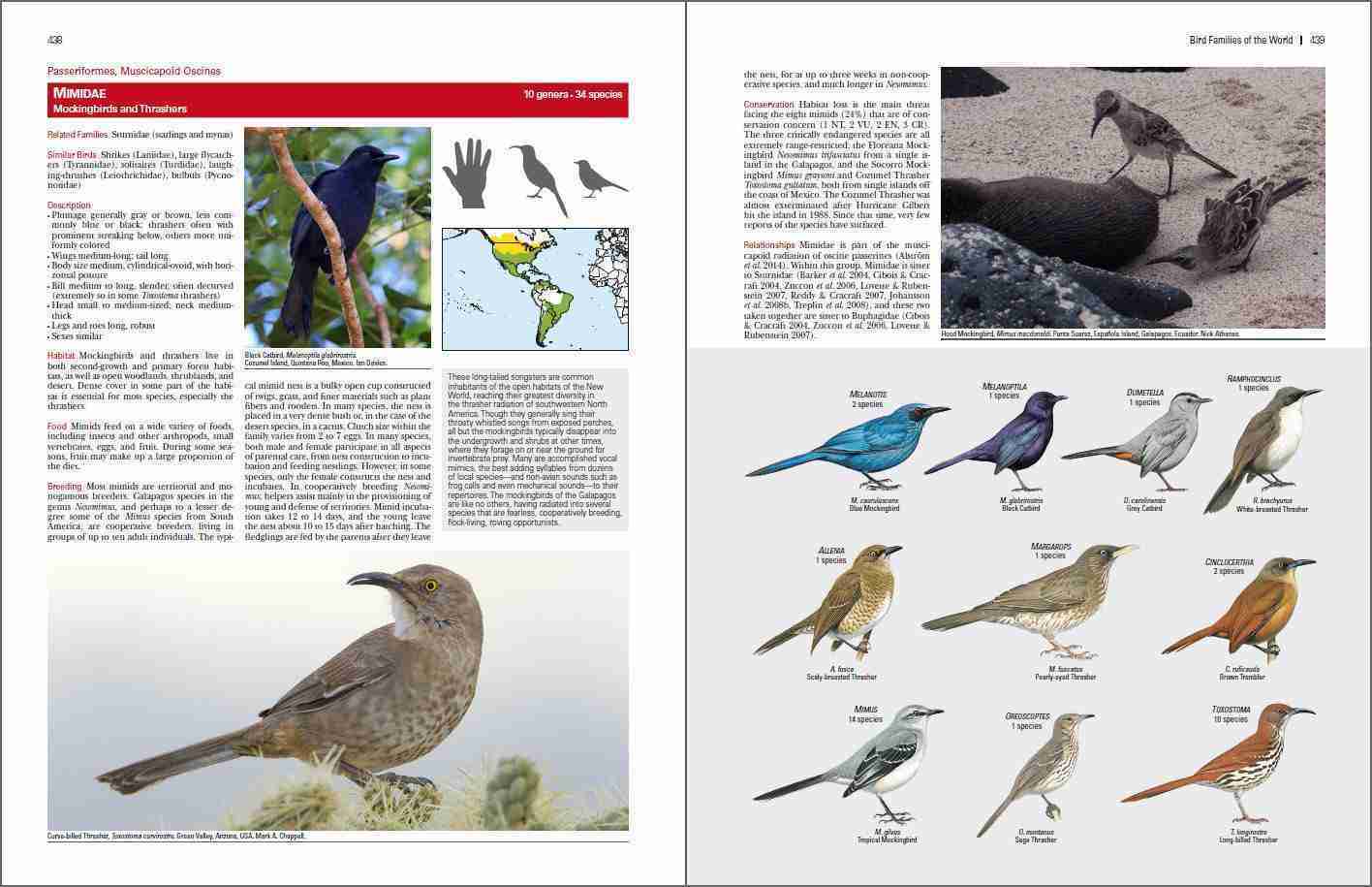

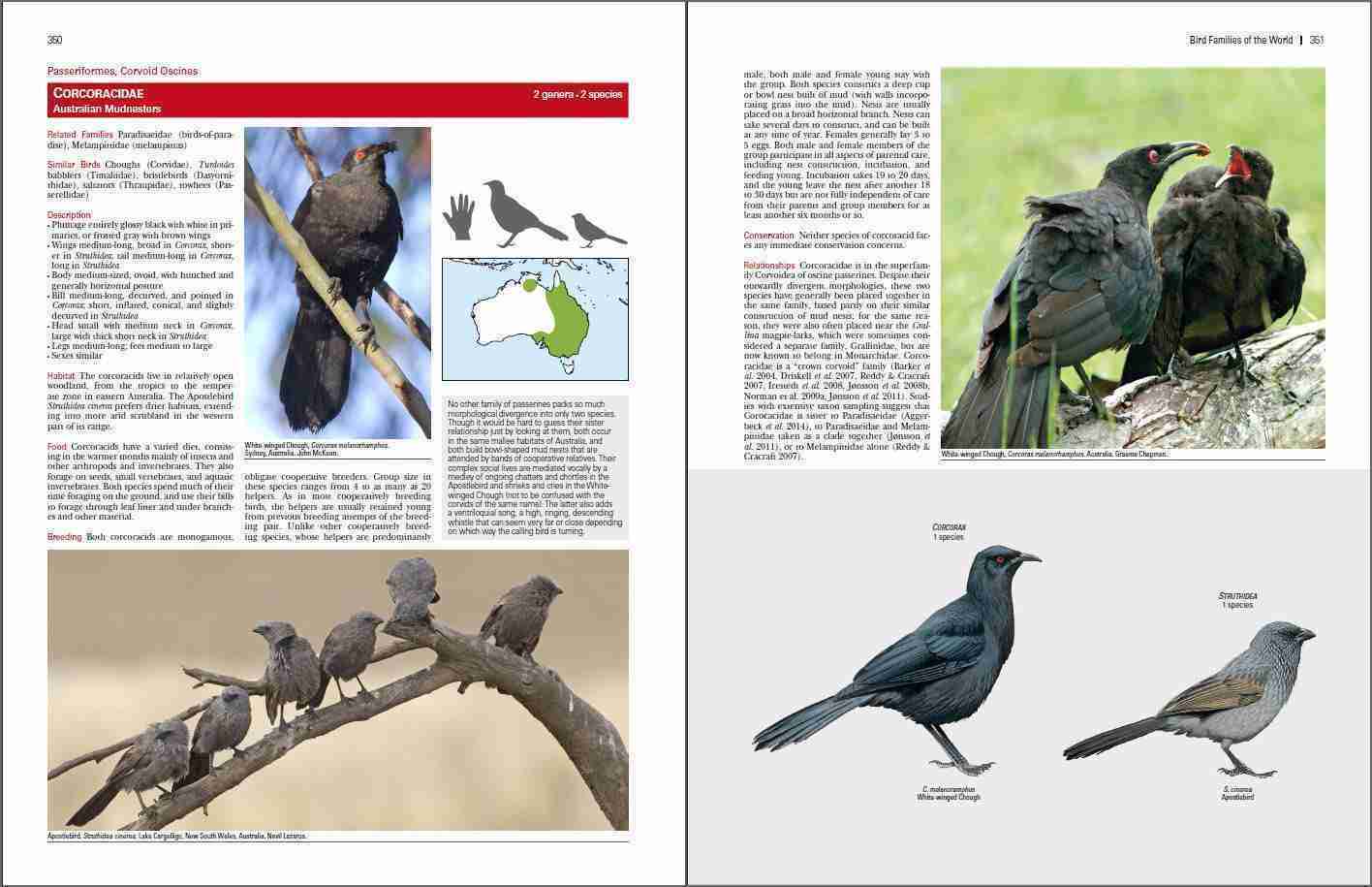

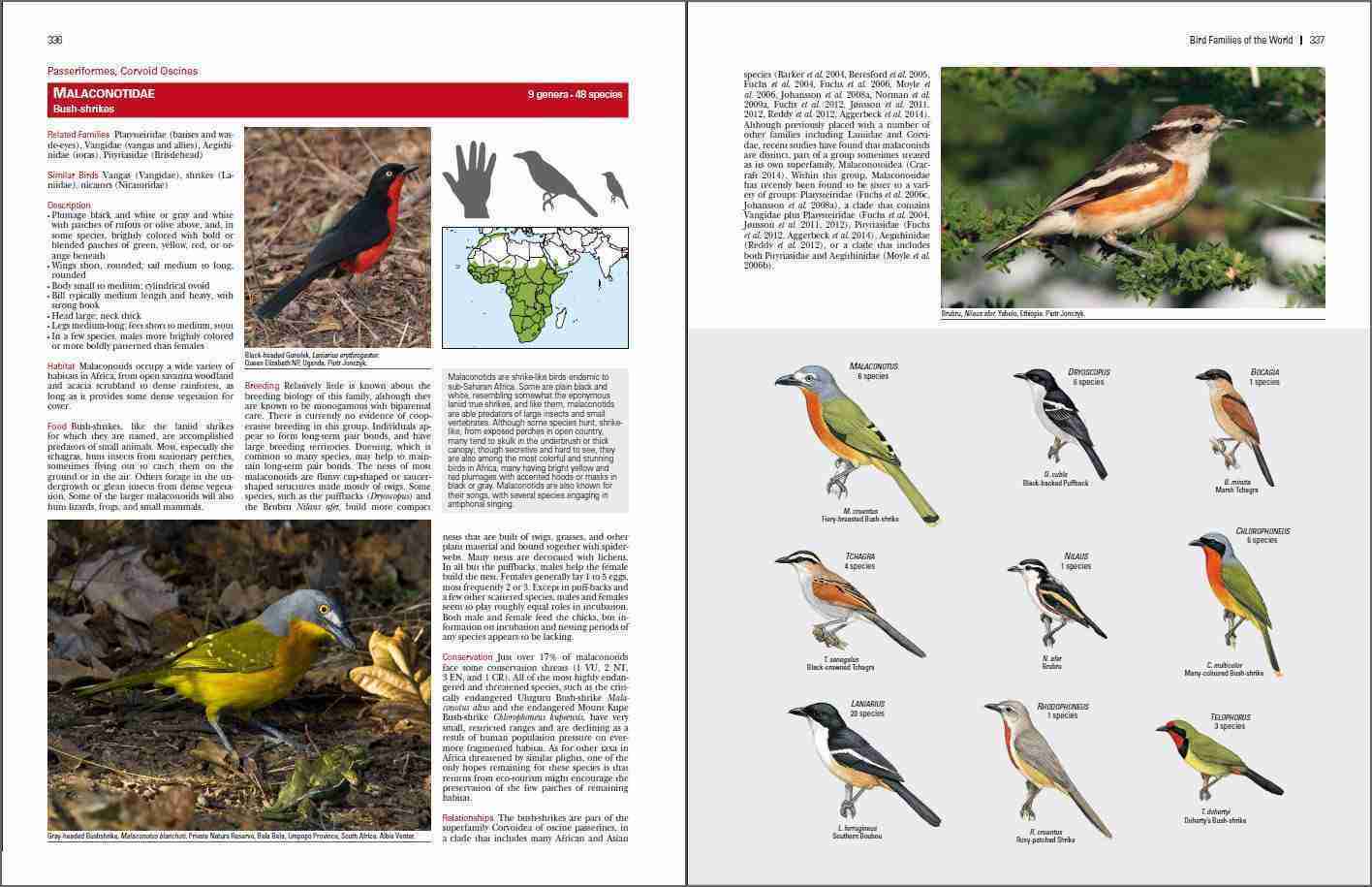

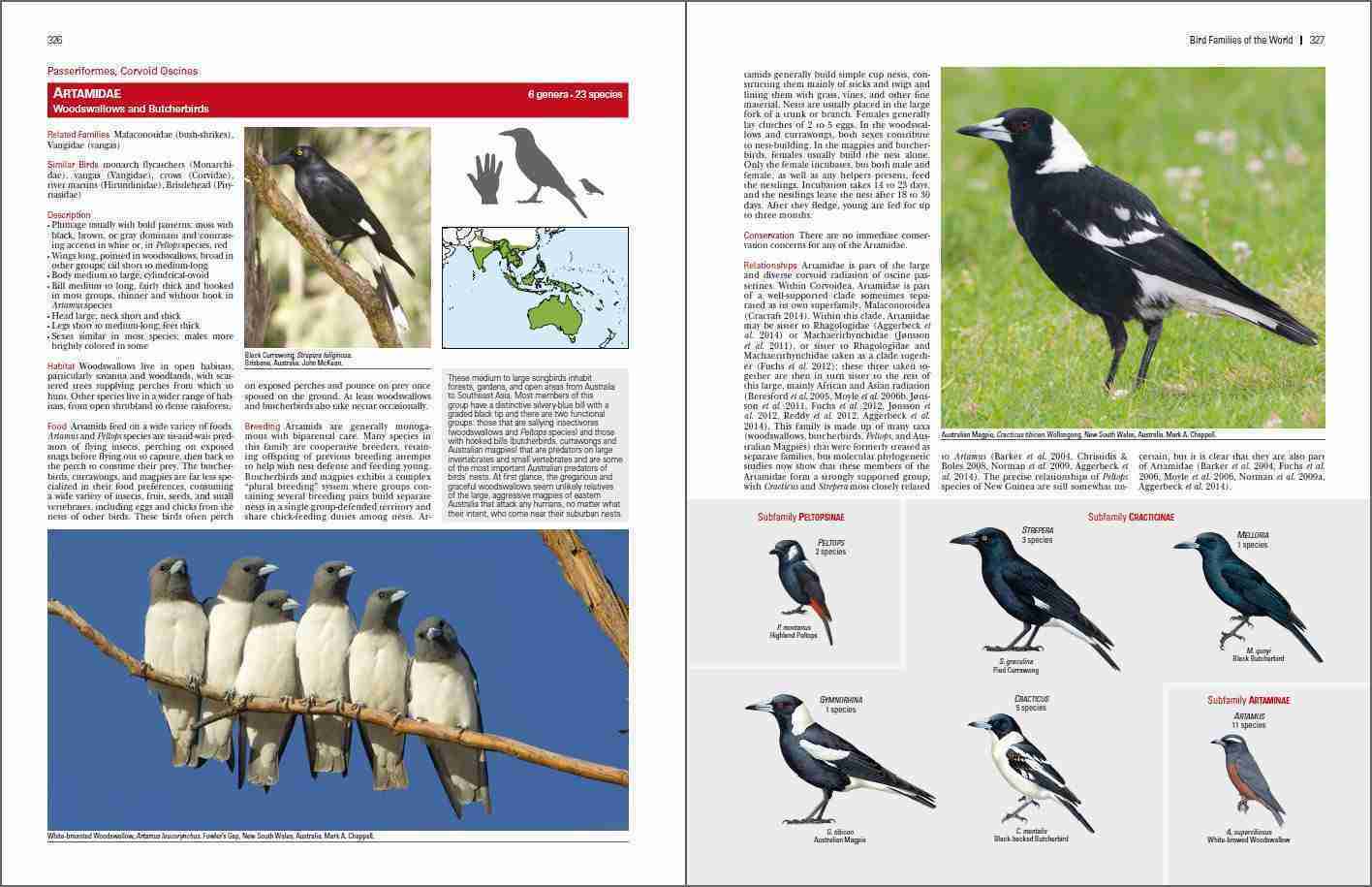

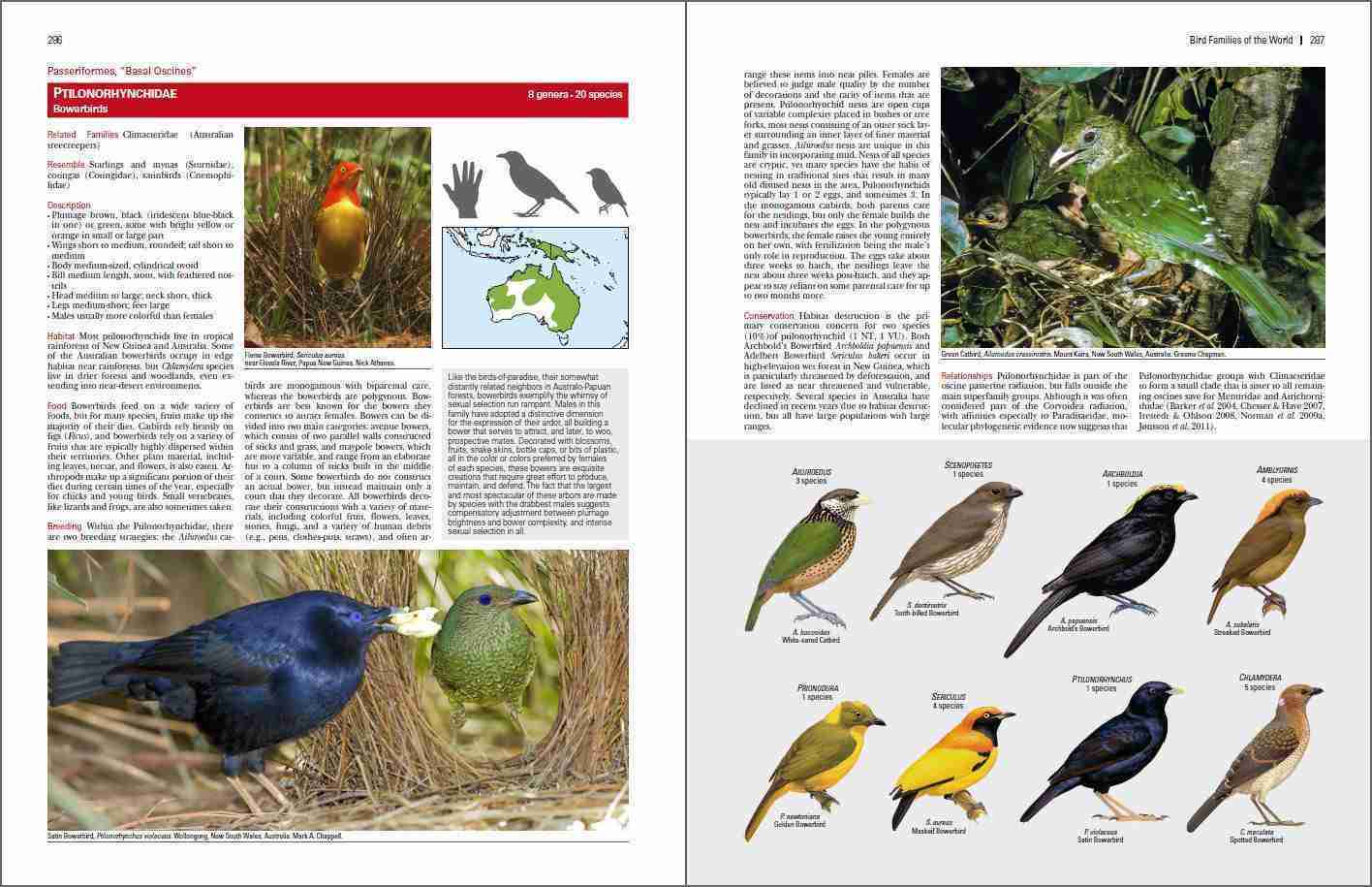

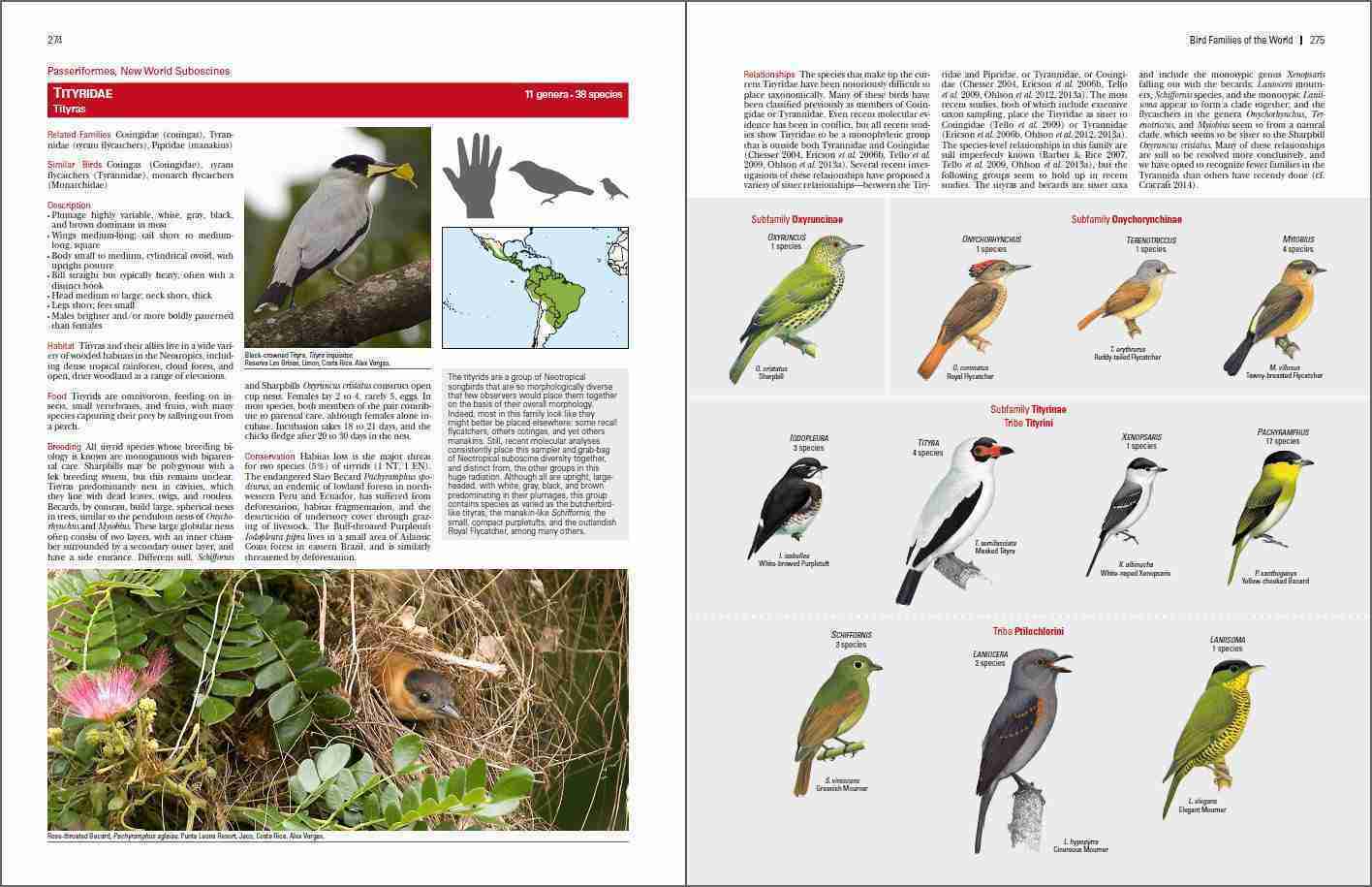

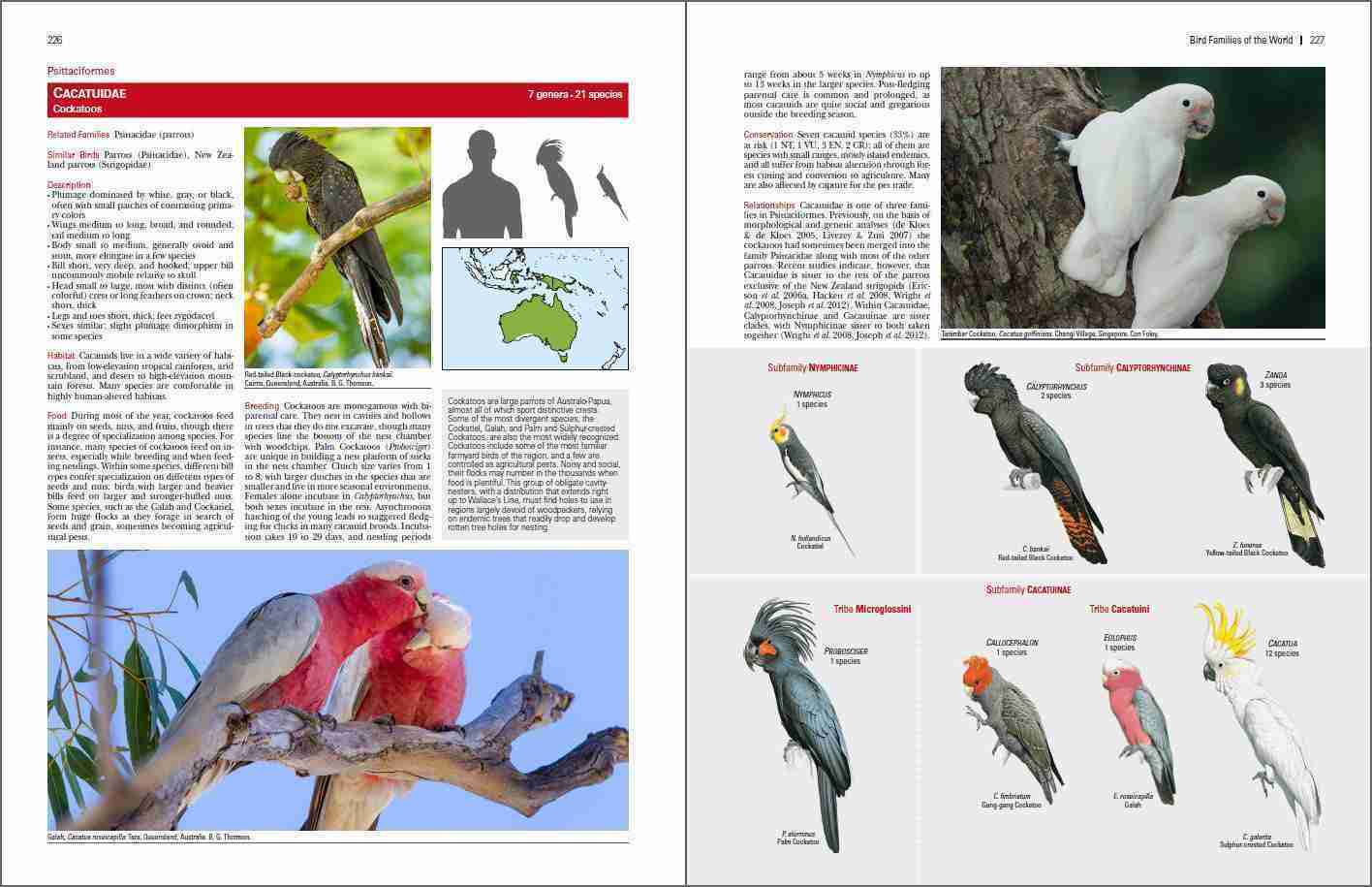

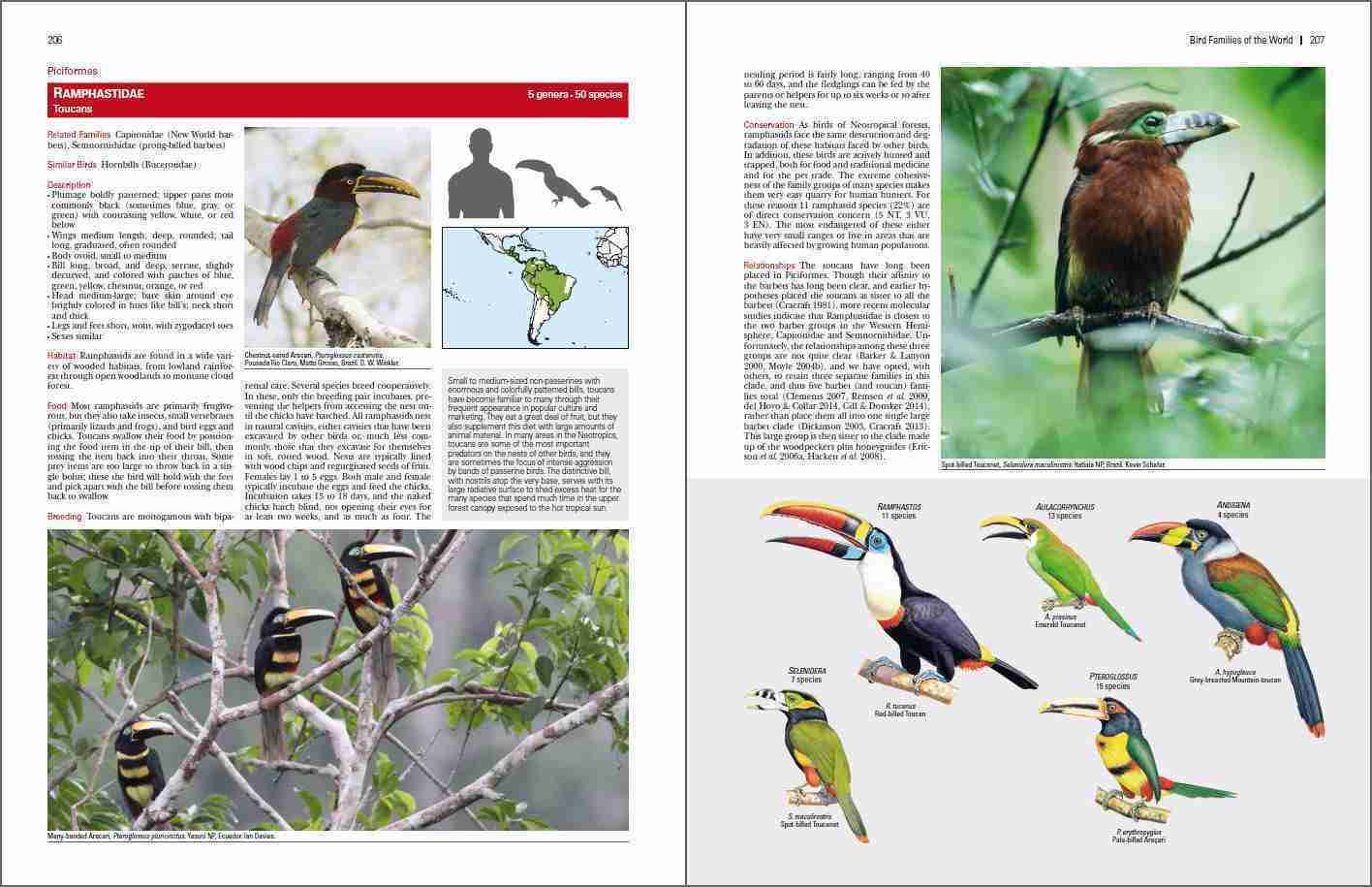

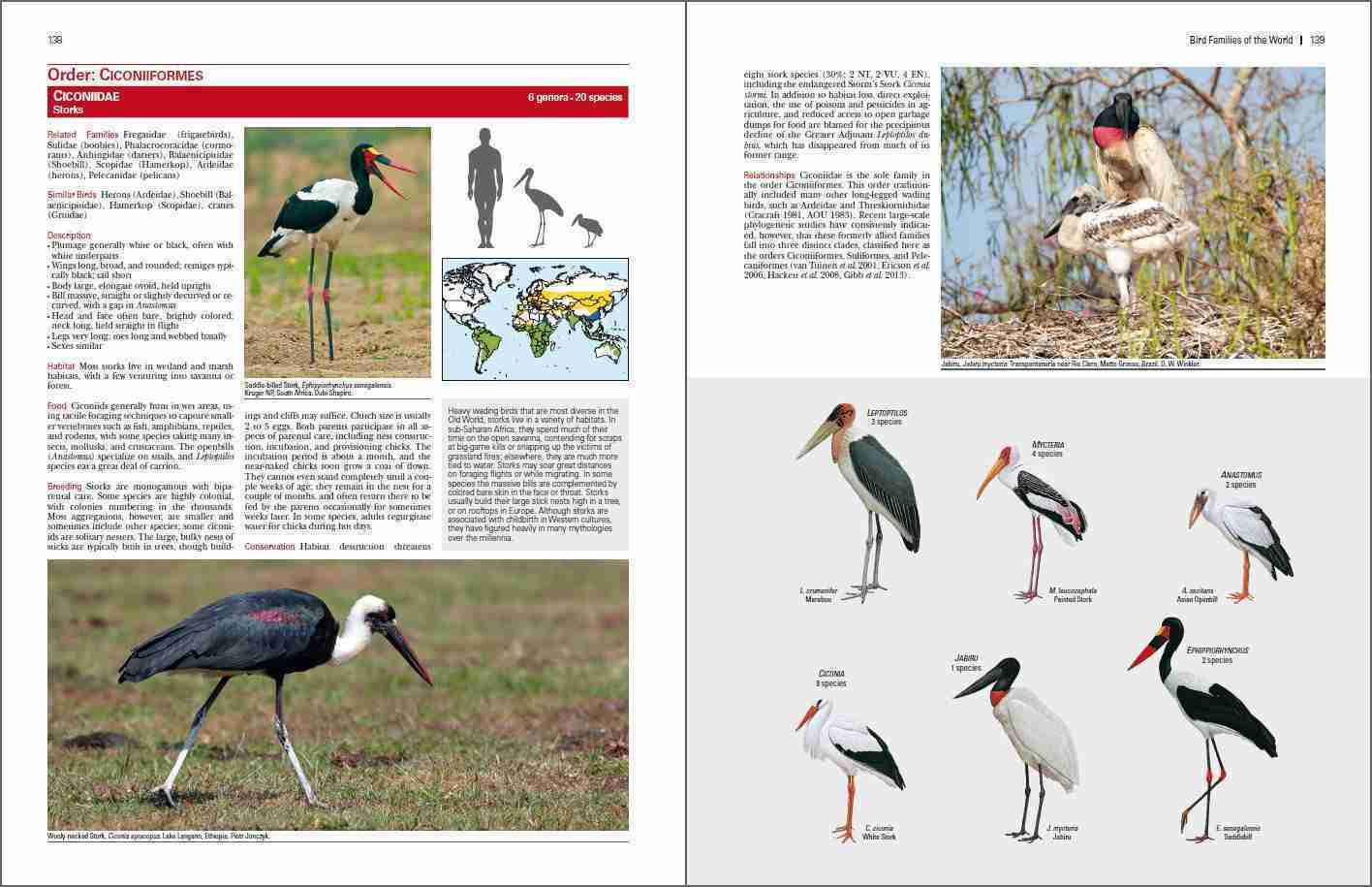

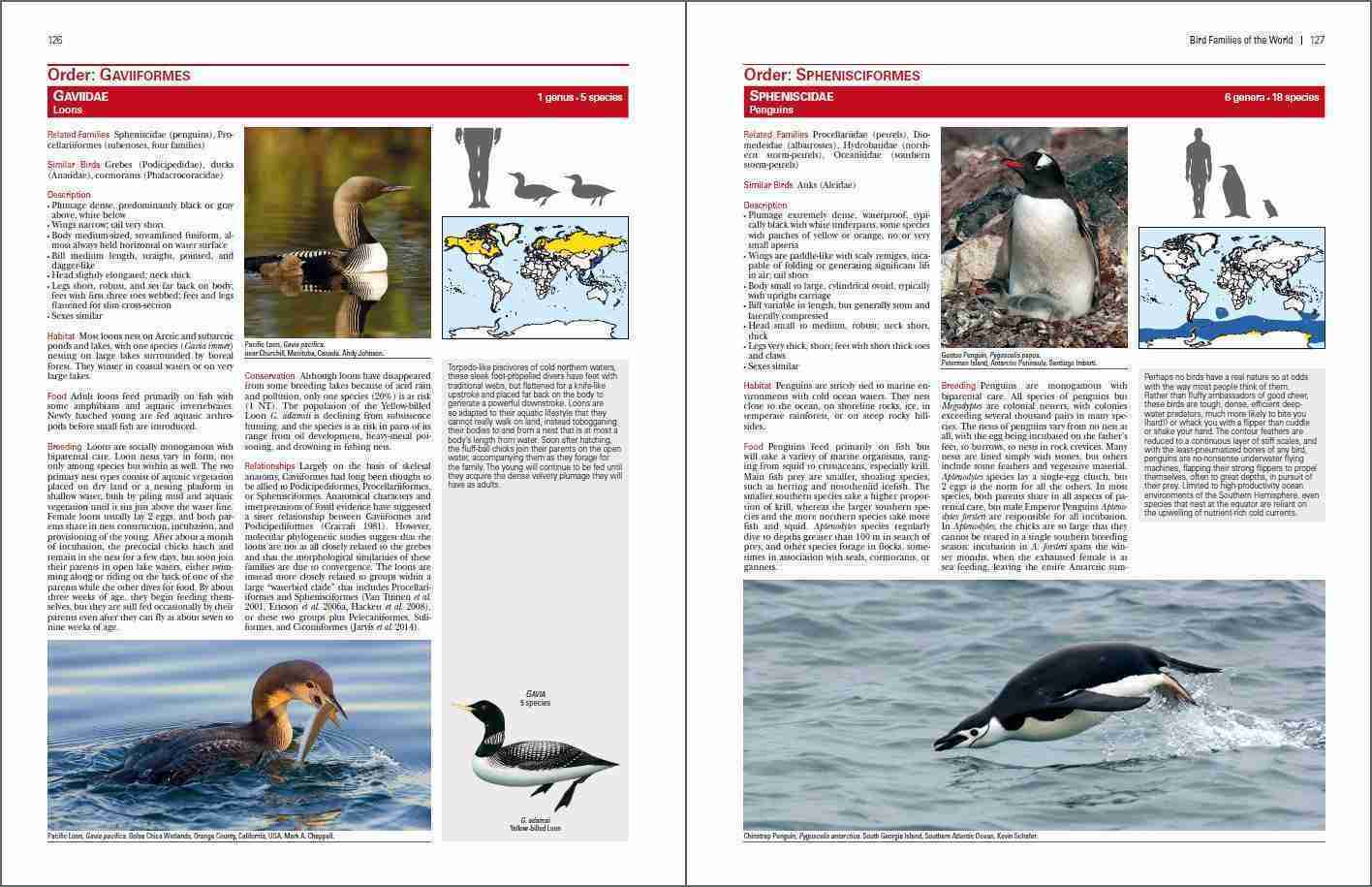

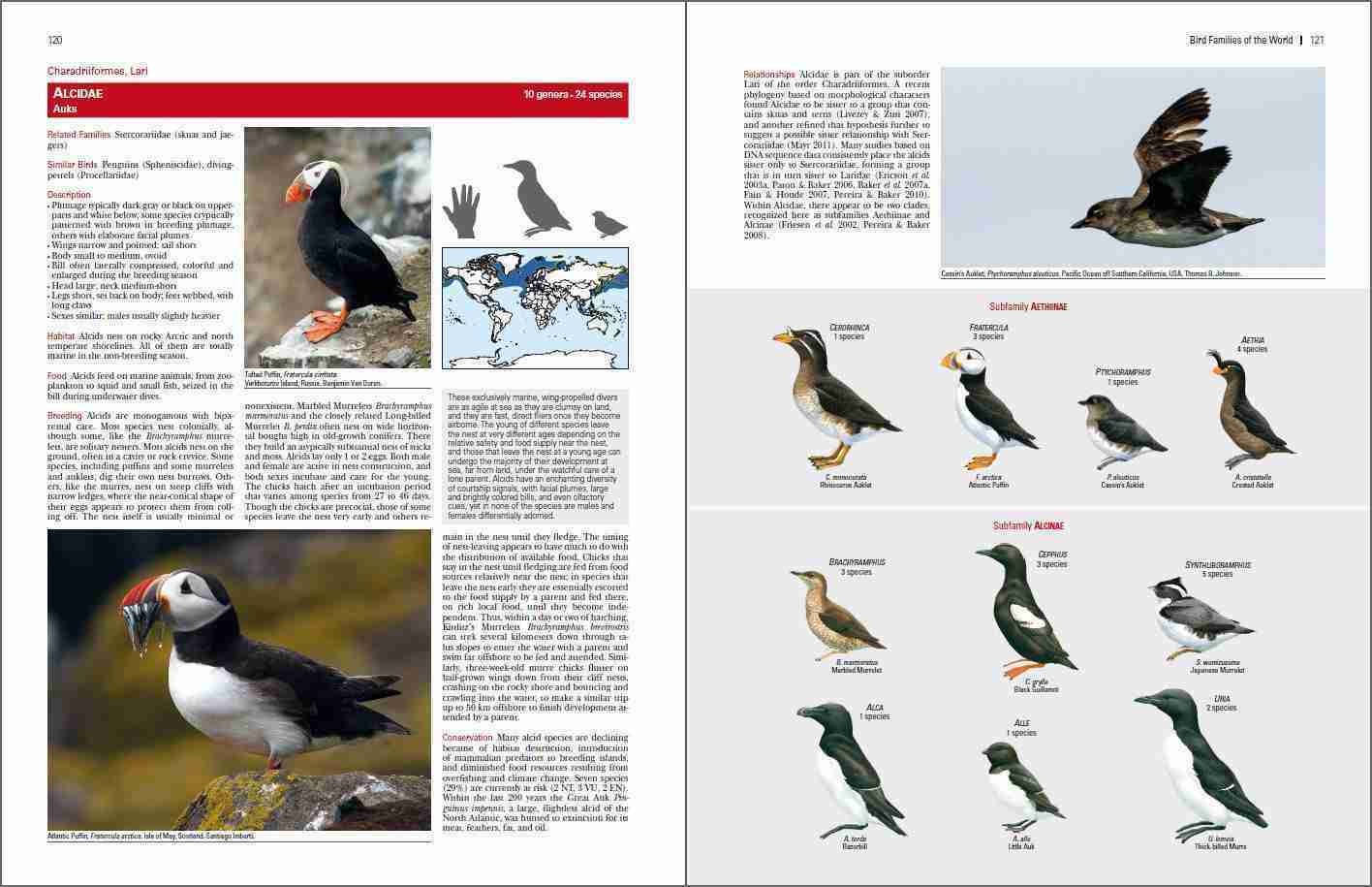

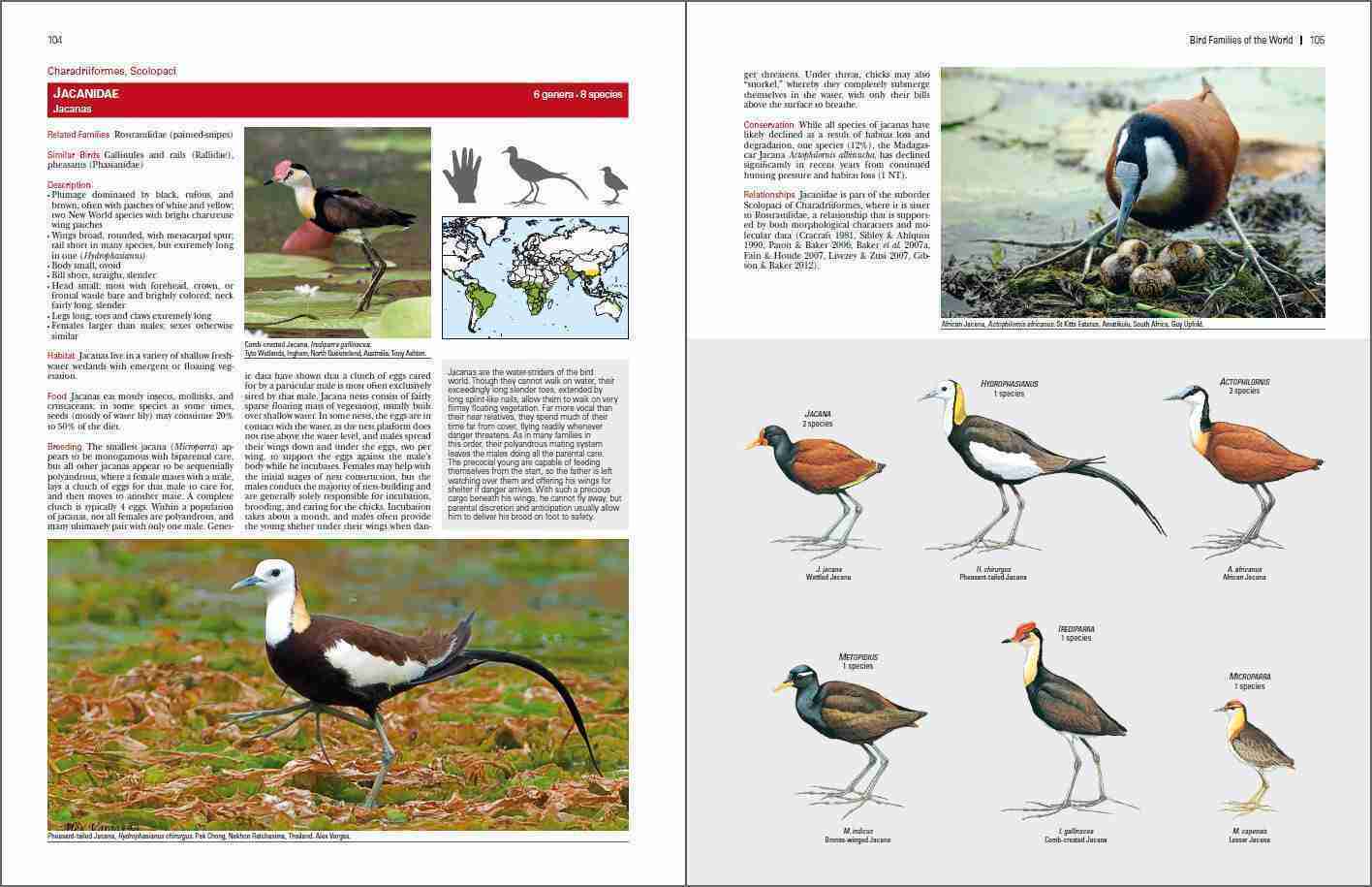

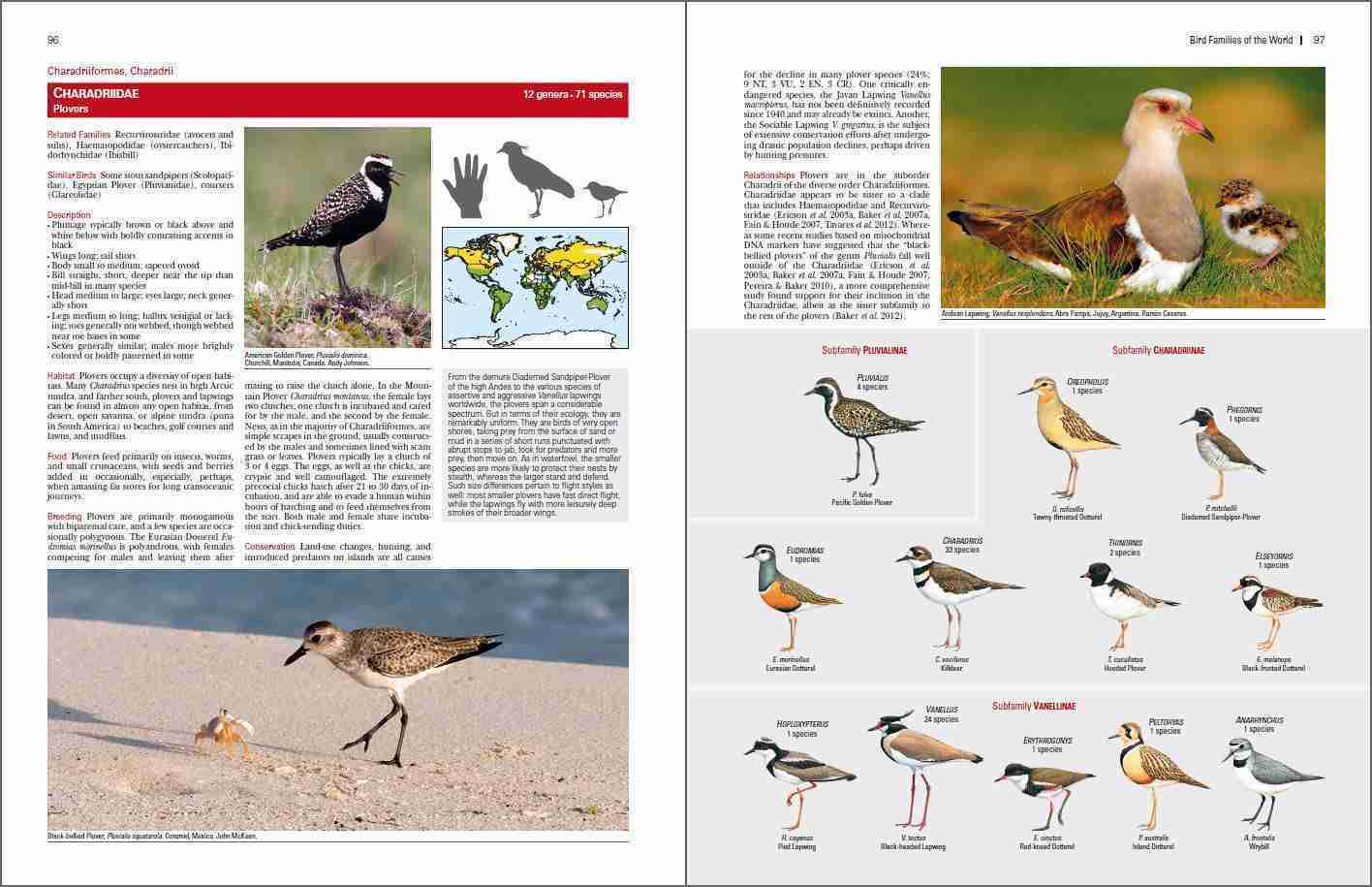

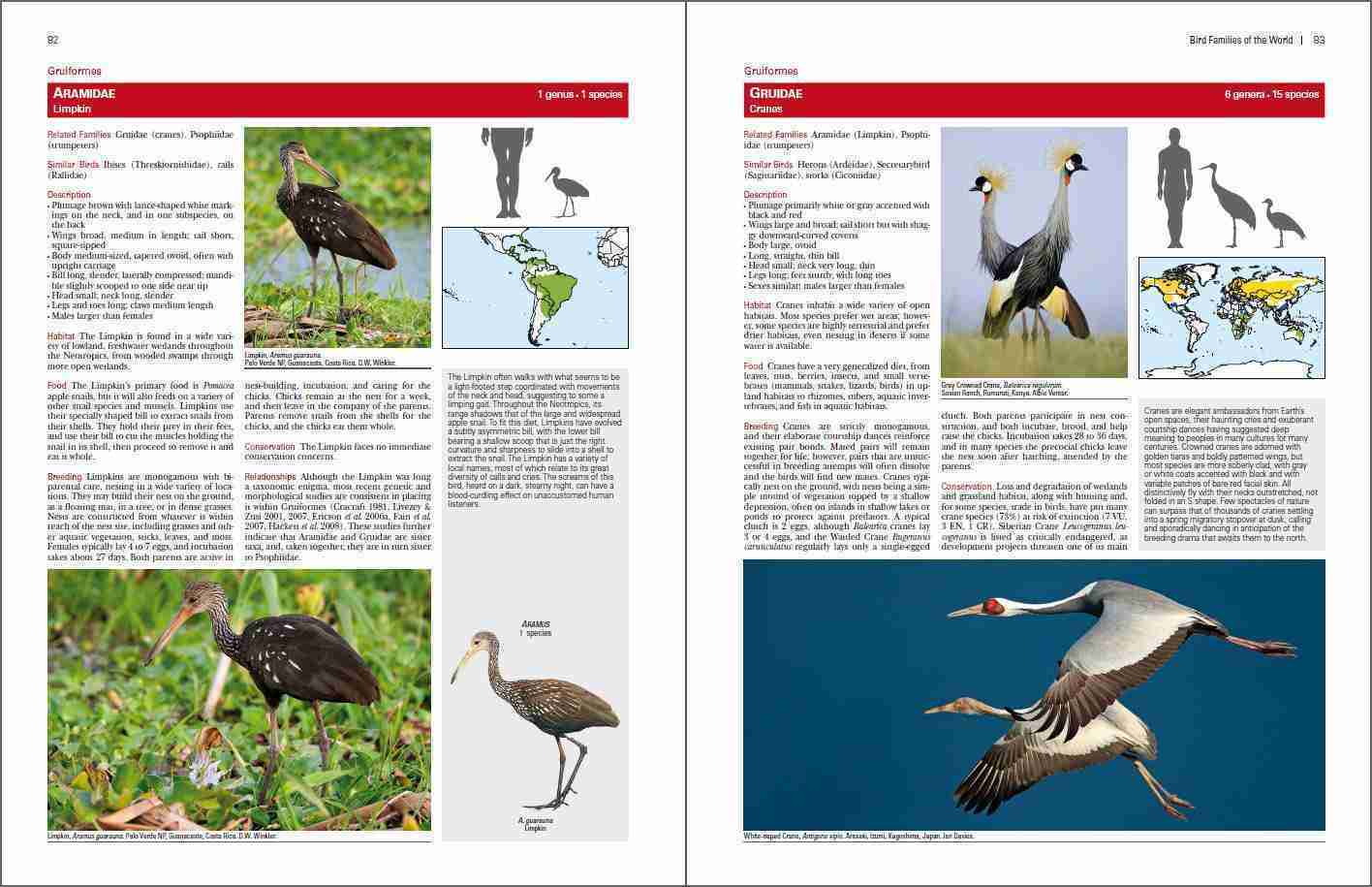

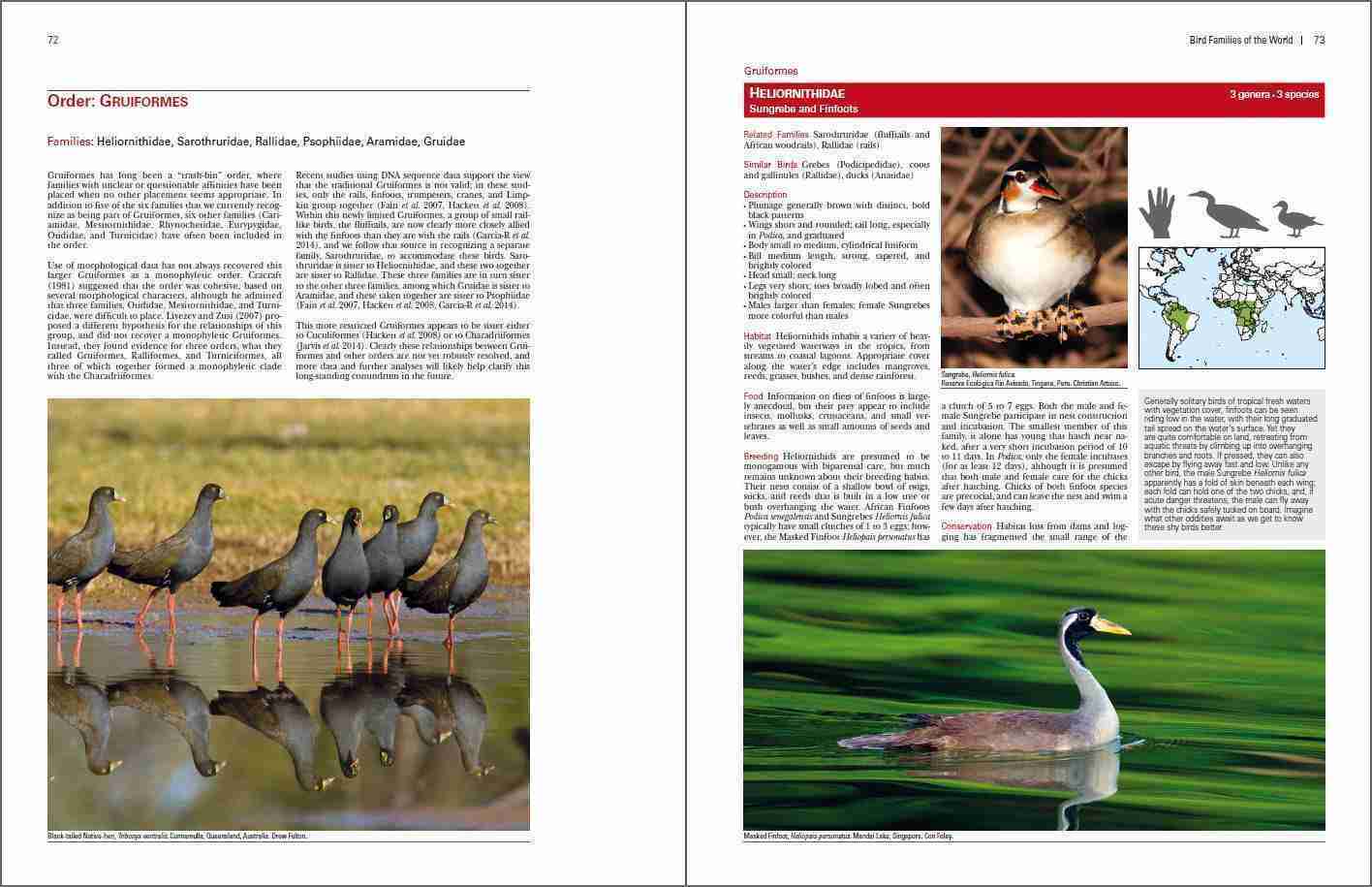

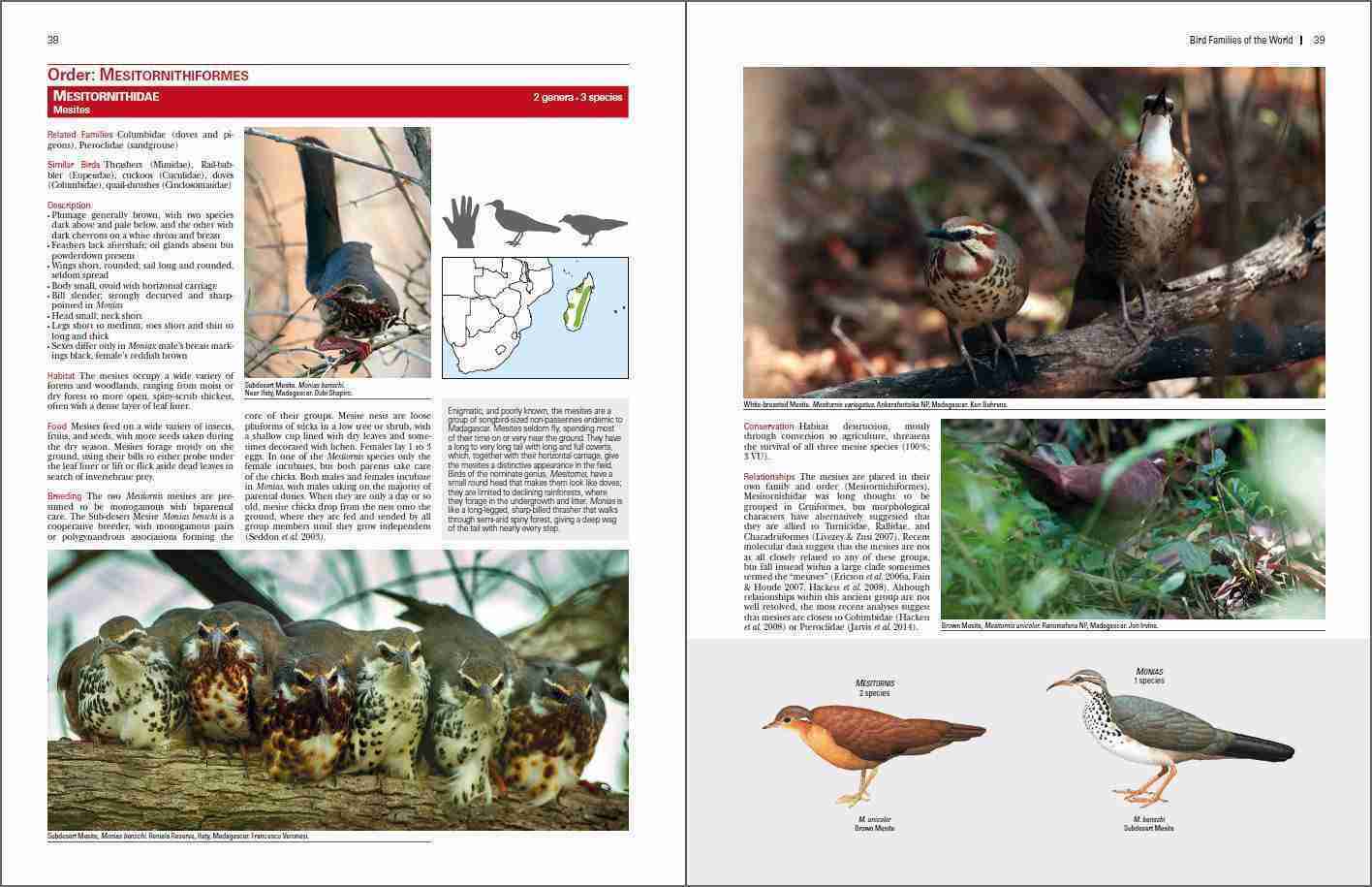

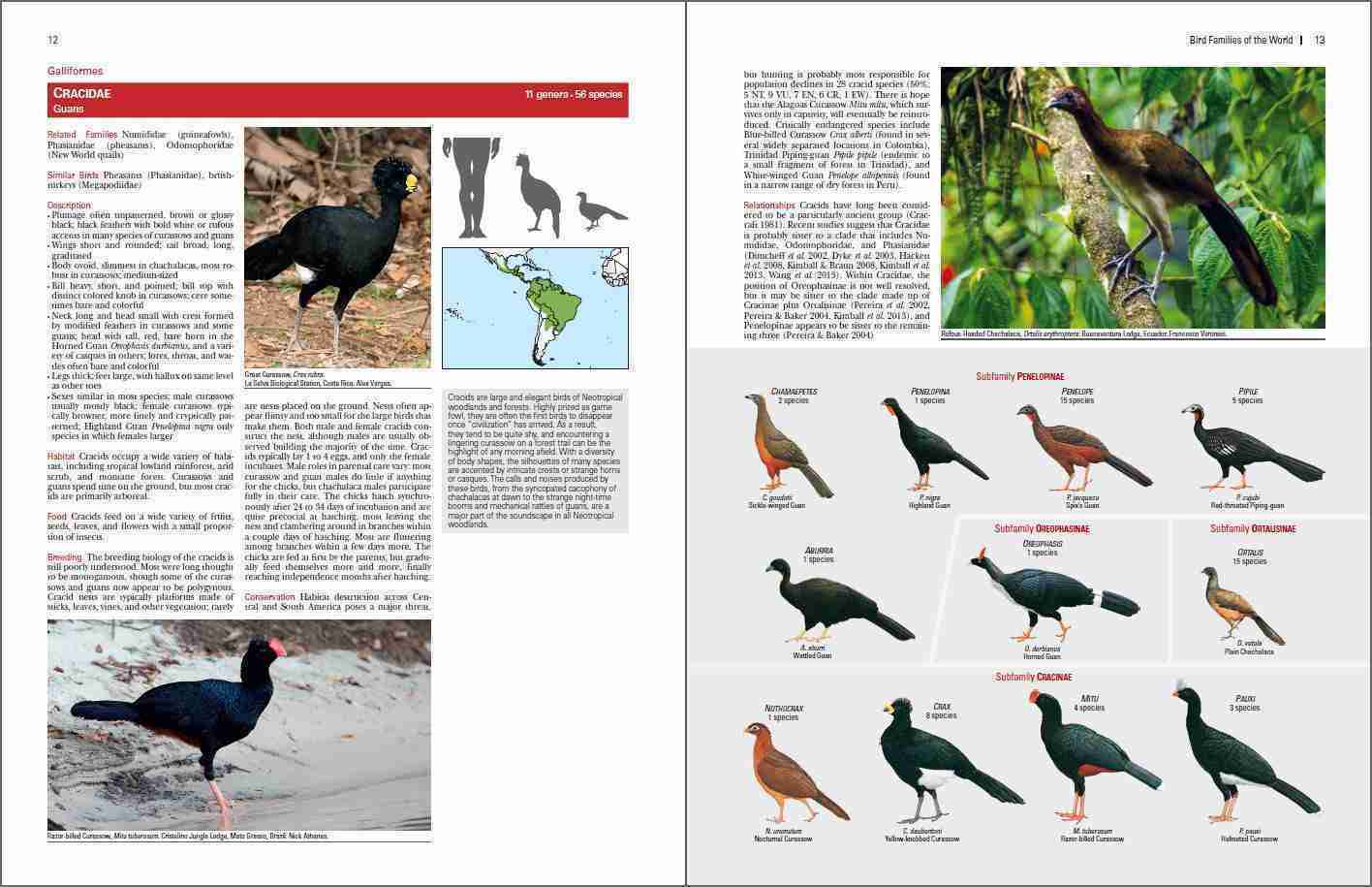

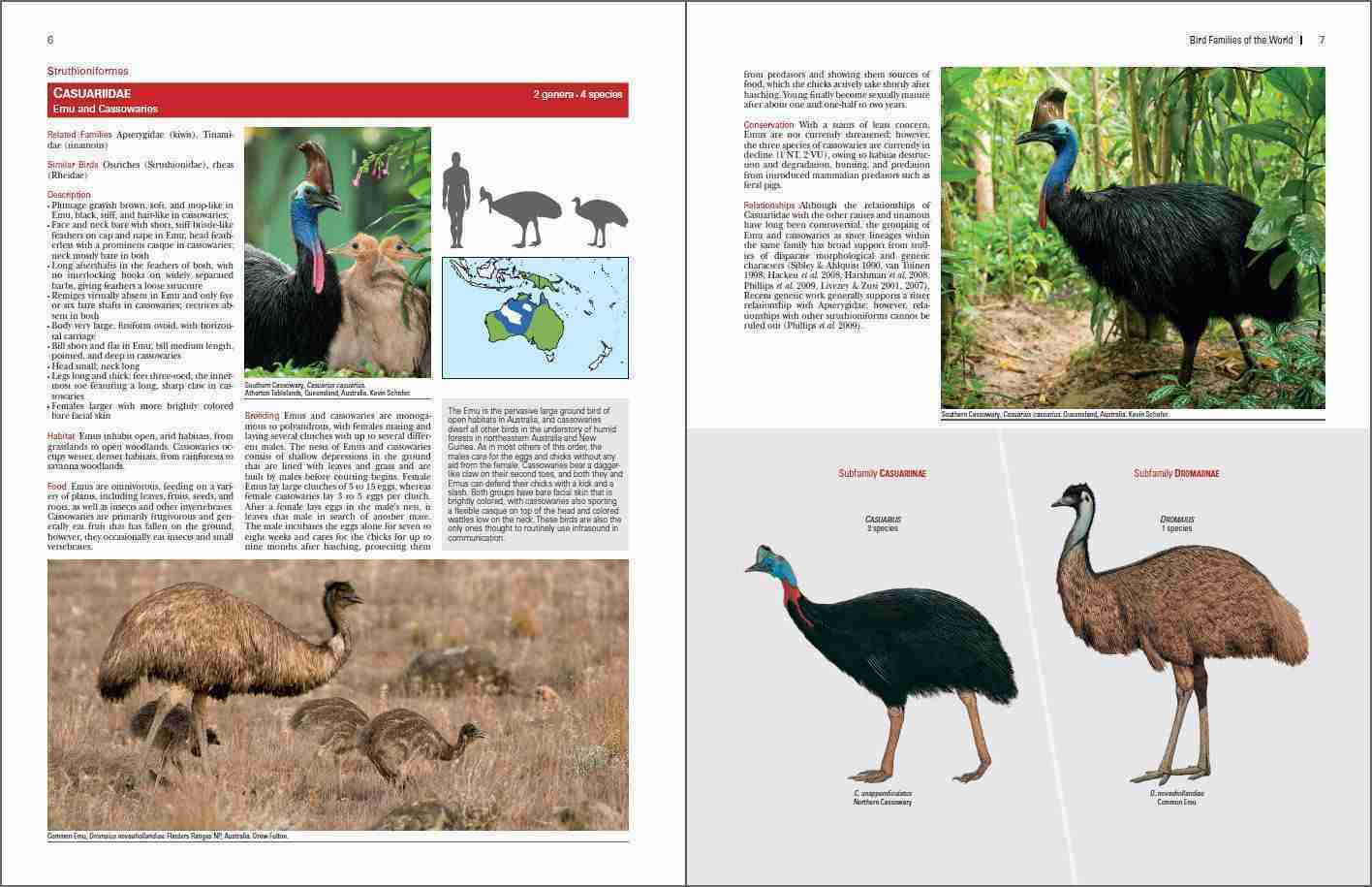

This book has been designed to serve both as a text for ornithology courses and as a resource for serious bird enthusiasts of all levels. Technical terminology is much reduced, and all scientific terms used are defined in a glossary. Introductory material describes the scope and concepts behind the classification used and gives suggestions about how best to use the book. The bulk of the volume is a family-by-family account of the birds of the world. For each family there is a distribution map with the breeding, non-breeding and year-round ranges of each family, a short text “teaser” to invite the reader to learn more, standardized descriptions of the appearance, relationships and similar species to each family’s members, their life history and conservation status. Each account includes a review of recent ideas about the relationships of the family to other families and relationships within it. The work is liberally illustrated by photographs from bird enthusiasts around the globe as well as paintings of one species from each of the genera in each family. It will be a beautiful and serviceable guide.

Features:

- 2417 bird illustrations

- 797 colour photos

- 252 distribution maps

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne –

If I may give my overall impression up-front, this is a wonderful book; probably the only book in this genre that provides a unique visual overview of the arrangement of the birds of the world by scientific orders, families and even down to genera. Lynx Edicions are well placed to do this thanks to the recently completed, monumental Handbook of the Birds of the World in sixteen volumes (plus a special volume) which was followed by the two- volume Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. The unique selling point of this book is that it is a ‘visual read’ of every order, family and genus and I do mean every genus; something that has never been done before. This is a standard setting book in the use of good design to create a book that allows people to process information intuitively and visually without having to digest a wall of text.

The layout is fresh, contemporary and exciting. The image selection has been terrific with sharp and well composed images. The plates allow an easy breakdown of the families into smaller taxonomic levels, down to every genus. The plates are also attractive in their own right and will appeal to those for whom plates are more aesthetic than photographs. Having said that, in this book the photographs are stunning and printed crisply with good colours and come off beautifully so that they are aesthetic as well as functional. The combination of plates and photographs works well.

After I received this book, I could not help thumbing my way through the entire book; a remarkable reaction given that it is a big book of 599 pages. I suspect many people who have birded around the world and are familiar with many of the world’s bird families will do this as it is instinctive to comb through the book to mentally checkbox families seen and those on the ‘to be seen’ list. The danger with this book is that it can steer you to being a birder who wants to see all or a significant proportion of the bird families of the world.

In addition to the visually interesting design layout, there are other clever features which make the design of this book strong and a good example of visual communication. I have already explained that it’s a ‘visual read’. More on this later. But it also brings in features I have seen in plant books such as the use of a hand to give a sense of scale. For bigger birds, the silhouette of a person is used. Where a family comprises different genera with typical sizes that are very different, this is shown by the use of grey silhouettes that show the range in sizes. Overview maps show the distribution of a family with the familiar colour-coding of green (breeding and resident all year), yellow (summer visitor) and blue (non breeding migrant). These are composite maps for the whole family. They work best where a family is confined to a zoogeographical region.

Let me expand on why I say this book is one that can be read visually. Let’s start with the ‘pictorial index’ on the inside front cover (for non-passerines) and the inside back cover (passerines). This is almost a numerical tabulation of all the birds in the world. The pictorial index has all the families separated by a green vertical border for the order and the families within it. A glance will show for example that the storks (Order Ciconiiformes) is fairly straightforward with just one family Ciconiidae. On the other hand, the Order Piciformes comprises several families; nine in fact, including the familiar woodpeckers (Picidae). It may surprise the person on the street that woodpeckers and toucans (Ramphastidae) are in the same family. Thus, even the pictorial index works to give a user an insight into the evolutionary relationships as currently hypothesised using molecular work. Within each of the orders, the number of genera is given together with the number of species. Thus, we read that there are 20 species of storks in 6 genera and 50 species of toucans in 5 genera. Thus you can count the orders, families and genera in the quick index, to compile a tabulation of all bird species in the world. The pictorial index is thus also a convenient summary of the birds of the world and the modern taxonomy. For example, the Order Chardriiformes much loved by birders and bird publishers for the technically demanding waders and gulls is seen to comprise three suborders of which the Lari has 6 families including the Laridae which contains the 101 species of gulls, terns and skimmers in 21 genera. A quick turn to the relevant page referenced from the inside front cover takes you to the Laridae section in which a plate shows you the five subfamilies in the family Laridae. The reader can see that the noddies are for example in the subfamily Anoinae and the gulls are in the subfamily Larinae. The gulls are distributed across eight genera. A representative species illustrates each genus with the number of species listed. It is easy to see that six of the genera are monotypic (i.e. one species only) with Rissa having the two species of kittiwakes and Larus containing 44 species. For anyone interested in the modern taxonomic arrangements and gaining a sense of how species fit next to each other in the higher taxonomic levels, this is a very easy and accessible way of being able to visualise the information.

There have been many books over the years that have provided an overview of bird families. In the last two decades, molecular phylogenetics have resulted in hugely surprising and counter-intuitive changes in the systematic arrangement of birds. This volume is one of a few that arranges bird families under more recent arrangements based on molecular work. But the big advantage this volume has, is that it is the only book that makes it so easy to visualise the taxonomic arrangement.

A ‘text contents’ page very clearly references page numbers to both the covering text for an order as well as for each of the individual families within that order. The text for the order is typically a fairly brief summary on the taxonomy, often a page at the most, including pictures. The family orders have a standard format with categories for Related Families, Similar Birds, Description, Habitat, Food, Breeding, Conservation and Relationships. The text is written in an accessible and interesting style. The one exception is the ‘Relationships’ category which is in scientific style and cross references the relevant scientific literature. The text is complemented by figures to indicate the scale, family distribution maps and the plates that break a family down into each genus, as already discussed. More complex families such as hummingbirds (Trochilidae) and Old World Flycatchers and Chats (Muscicapidae) break down into subfamilies and within them tribes. Having read a number of family accounts in this book, I felt that the text has been written very well to capture the essence of a family with great economy in the use of words. To write with such economy and yet capture the essence of a family requires great skill. However, readers may well wish to consult other books that carry more text or look up some of the papers that are cited. In grey shaded boxes are additional text carrying the kind of insight which in today’s world of education outreach may be billed as ‘fun facts’.

This book will hold a lot of interest to world birders who may not have the time to keep abreast of what is published in technical journals. For example, it makes clear how the Order Caprimugliformes is now considered to include nine families which comprise the swifts, treeswifts and hummingbirds previously included in Apodiformes, but now within the same order as frogmouths and nightjars. One also encounters new families such as the fairy flycatchers (Stenostiridae), which includes species such as the Grey-headed Canary Flycatcher- a bird very familiar to me. The passerines are divided amongst twelve groups. What in many traditional field guides were grouped as flycatchers are now spread across three of these passerine groups. To make sense of all of this, the section on passerines starts with a diagram (figure 11 on page 268) which shows the modern phylogenetic hypothesis. The authors are clear to point out that this is a provisional hypothesis. More molecular work and refinements to how the data is used is likely to result in changes.

The meat of this book is the family accounts. But the front sections are worth a careful read to understand some of the nuances of molecular phylogenetics and why the authors treat current arrangements as hypotheses. Figure 8 on page 23 illustrates the molecular phylogenetic arrangements for birds used in the book covering all the families and showing an example of a linear arrangement. If the reader is wondering why this is not the same linear arrangement followed in the book this can be deduced from Figure 4 which explains the concept of ‘node spinning’. Essentially the ‘node spinning’ example shows how a phylogenetic relationship could be shown in one of four different linear arrangements, all of which are correct, but which may appear to give different results to a reader. The introduction contains a primer of the classification of birds, phylogenies and avian classification and the meaning of higher taxonomic ranks. A world map (Figure 9) shows the number of passerines and non passerine families endemic to each biogeographic region. These summary facts are expanded in pages 26-28 to show visually the endemic families. Again, this works brilliantly, for example to remind people that in Africa, familiar birds such as Ostrich, Hammerkop, Secretarybird and Shoebill for example are amongst 27 families endemic to it. The end sections have a list of the literature cited and a glossary.

The cover of the book is intended to tell the story of how some families of birds are confined to certain parts of the world. Although this works, I don’t think the cover does justice in terms of visual impact to a book which is so well designed and beautifully presented. The large format helps with the layout. However, such an absorbing book would see a lot more usage if it were of a shape and weight that people could carry to read on the office commute on a train.

It is very rare to have a book so deeply anchored in science; in this case in the science of molecular phylogenetics, but yet to be so beautiful in the use of images and artists’ plates. Any world birder whose interest extends into understanding the ecology, biogeography and evolutionary relationships of the world’s birds will find this book fascinating.

Sandra Jacobson –

Bird Families of the World is a treat of a book. It is gorgeous, once again using the well-done illustrations in the two volumes of HBW’s Checklist of the Birds of the World, but in a different format. This work focuses on the families instead of all the species, although it does go down to the genus level in illustrating one species of each genus in each family. This overview of the genera is quite interesting because it shows the similarities and differences within families. Of course, the several taxonomies used throughout the world mean that this book will not agree with several of the family placements, but this is also a strength of the book because it has a detailed section on taxonomic relationships. Since all the taxonomies use peer-reviewed literature as their base, the compilation of some of these works is helpful for those who want to delve into this detail.

The level of detail is actually one of my complaints with the book, varying from overbroad to very detailed. The overview of family characteristics fails to give several anatomical features that are usually noted in treatments of family (or order) characteristics. For example, as a random book opening, toe arrangement is lacking in the description of Strigidae (typical owls) but body shape is included. I would have liked a more thorough treatment of these characteristics. Why are barn owls separated from typical owls? Why are frogmouths separated from potoos? Is the convergent evolution of sunbirds and hummingbirds different under the feathers?

The most interesting part of each family account is a text box with an anecdote about the family. These could almost be considered ‘stories’ about each family, although they can relate some fascinating details. I learned more from these short paragraphs than the bullets about family characteristics.

I was uncertain if it would be worth my money to purchase yet another book with the same illustrations as the Checklists (which I adore, and spend a huge amount of armchair birding time on), but indeed this book is worth it. I have enjoyed reading and just browsing through the book, and of course I’ve learned a lot as well. I’ve concluded that if you enjoy the Checklists, this book is a fine complement, and may even encourage you to purchase the Checklists too, because I’ve often gone from the Families book where one species of a genus is illustrated to check out a few others as well.

(Note to the reviewer above: Toucans and woodpeckers are not in the same family. They are both in the same order, Piciformes, but toucans are in the family Ramphastidae and woodpeckers in the family Picidae. I would let this pass except that it implies the book is incorrect, which it is not. I also agree with him that the cover illustration is not as lovely as the rest of the book.)