Latests posts

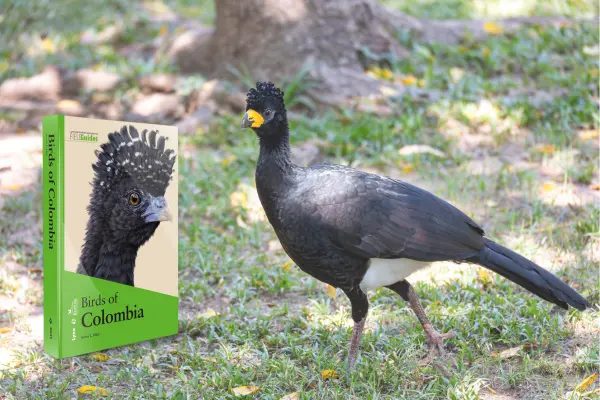

Birds of Colombia: A Journey Through the World’s Most Bird-Rich Nation

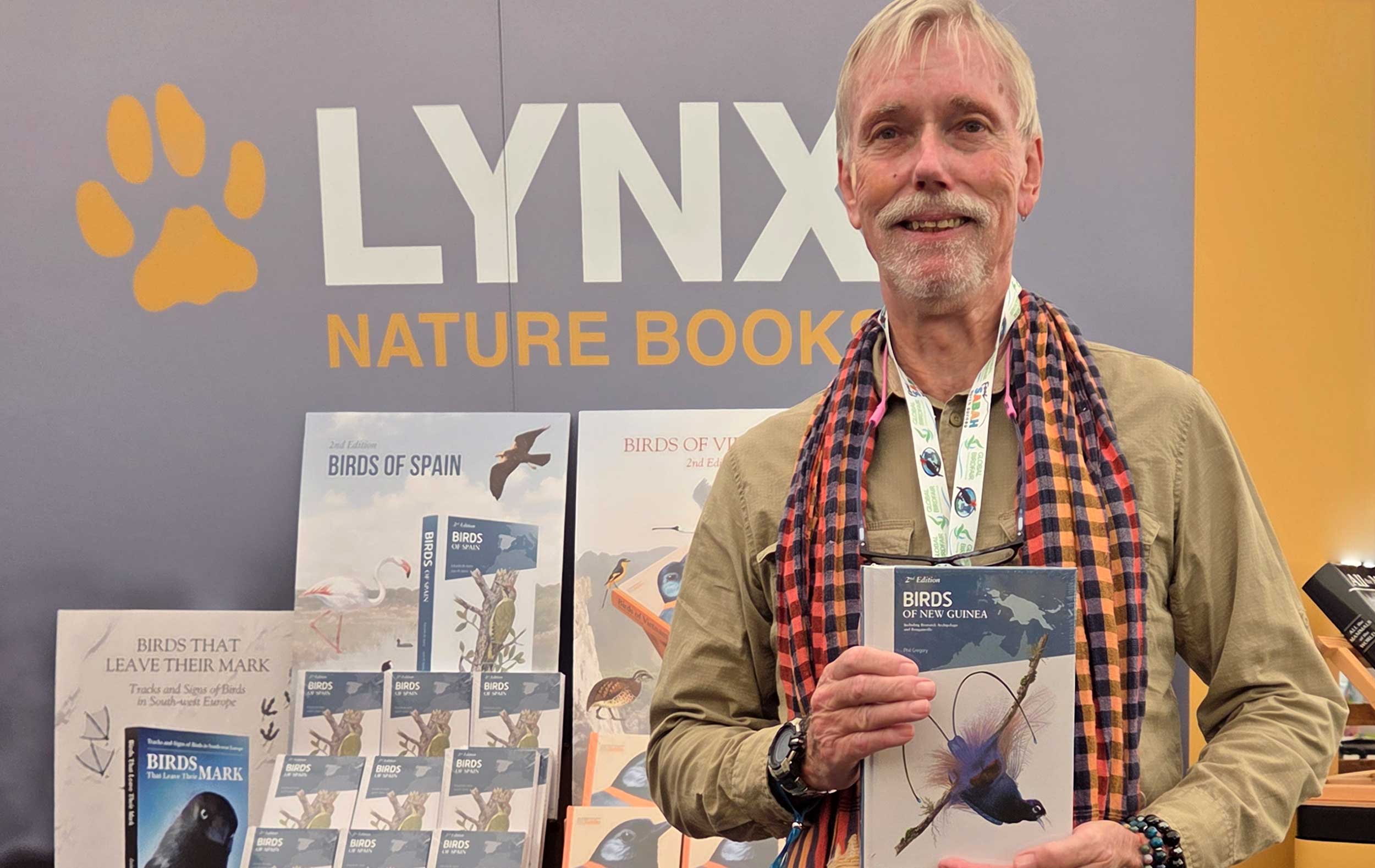

Birds of paradise and beyond: the new edition of Birds of New Guinea

Birdwatching in Spain: a guide to species, habitats and the joy of birding

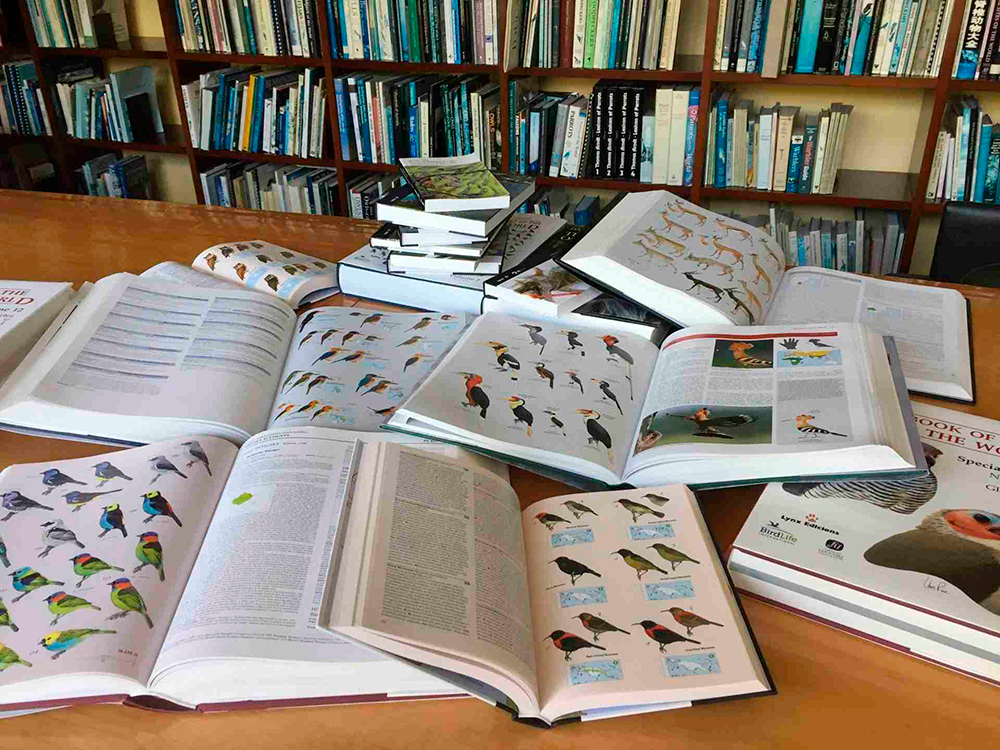

Why books matter for nature: the role of scientific publishing in conservation

Vietnam’s birds revisited: an interview with Richard Craik on the new edition of Birds of Vietnam

Seabirder, author and artist Peter Harrison discusses “SEABIRDS: The New Identification Guide”

Once bitten, twice shy: between the covers of the second edition of the Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago

Taming the wild world of mammalian taxonomy with Connor Burgin

As the HMW series crosses the finish line, we look back at its course with Chief Editor Don Wilson

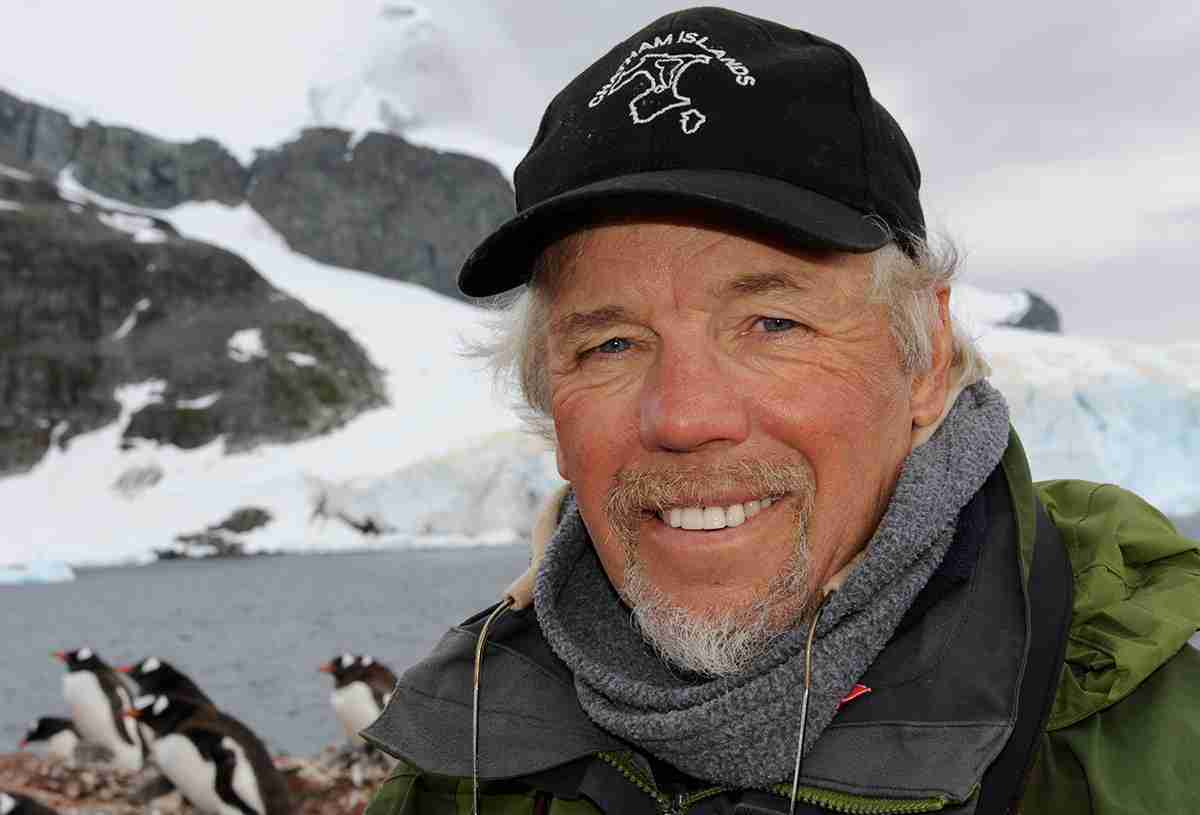

Don E. Wilson is a Chief Editor of the nine volumes of our now-completed Handbook of the Mammals of the World series. He was a good choice for the role, given his long career in the field and his collaboration as author and editor in important works in mammalogy, including the landmark Mammal Species of the World, as well as his many contacts in the discipline and his vast knowledge on the subject matter. Now that the HMW series has made it across the finish line with the publication of Volume 9: Bats, we want to hear about Don’s views and experiences of the project, including how he helped the series out of the gate and the various hurdles encountered along the way. A big congratulations to Don and the entire HMW team for this achievement!

How did you begin your involvement as a Chief Editor of the Handbook of the Mammals of the World?

Josep del Hoyo came to Washington in the 1990s and approached me with the idea of putting together the Handbook of Mammals of the World. At the time, Lynx was about 5 volumes into the Handbook of Birds of the World, and already Josep was thinking of expanding to mammals. Interestingly enough, I had been thinking about a similar project for some time. I had talked with a few publishers, but we couldn’t agree on the scope and depth and breadth of the project. I had shepherded a couple editions of Mammal Species of the World through publication, and was keen to use that taxonomic backbone to provide a more complete summary of everything known about each species of mammal.

Most publishers were not keen to provide an account of every single species, because obviously there are lots of obscure species of rats and bats that we know very little about, and that most people have never heard of. When Josep outlined his ideas of doing a very complete coverage of all species, and of doing it in Phylogenetic Sequence, showcasing what we know of evolutionary relationships, it matched my ideas completely. I quickly agreed to take on the task of Chief Editor, and we began fundraising for the first volume.

Please explain the important role you played to get the best specialists for every mammal family to participate in the series.

Josep wanted me to do this because of my involvement as Editor of Mammal Species of the World. Spending two decades working on that project had put me in touch with most of the leading mammalogists in the world. I had also served as President of the American Society of Mammalogists, which gave me many additional contacts. I had also edited The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals, a project that involved more than 200 collaborators, so I had a pretty good feeling about how to go about convincing authors to participate in this type of undertaking. We wanted the very best experts in each family to take the lead on producing the accounts. In many cases, my contacts with the leading specialists also allowed us to access the best and brightest of upcoming students and Post-docs to participate in the project. Many times, a leading specialist would be extremely busy, and would suggest colleagues, graduate students, or Post-doctoral Fellows who might serve as co-authors. This assured us of getting the very best people involved, and greatly expanded my reach beyond my initial contacts.

What were the biggest challenges of the HMW series, in your opinion, compared to previous works like your seminal Mammal Species of the World?

What were the biggest challenges of the HMW series, in your opinion, compared to previous works like your seminal Mammal Species of the World?

This series is much broader in scope than MSW and required us to go beyond the taxonomic experts in each group of mammals. One of the most difficult things was to convince the very best people to take on the challenge of producing a family account, or the complete species accounts. The very best people are often also the busiest people, and many are reluctant to take on the burden of producing something on a tight deadline that might interfere with their normal research schedules. My pitch was always that this project was going to be an opportunity to produce a complete, up-to-date summary of the very best scientific data available for every group of mammals.

Probably the biggest challenges revolved around getting folks to meet our deadlines. Obviously with such a huge project, we needed to keep things moving in a very timely manner. Academics are notorious for not meeting deadlines, so we had to spend an inordinate amount of time reminding authors of the importance of timeliness. Other challenges included things like simply finding experts for some obscure families and often we had to combine folks with different expertise in different genera or species to eventually put together a unified picture of the family in question. One lesson we learned along the way was that it is much better to have a single lead author, and to let them put together a compatible team rather than for us to try to force people to work together.

Which one volume of the HMW series would you say was the most challenging from your point-of-view and why?

I think the Rodents were the biggest challenge for many reasons. We knew going in that rodents were going to be a challenge. They are the biggest group of mammals, and we eventually had to split them into two volumes. This was easy enough to do, and we managed a pretty effective split, but finding experts in all of the different families, genera, and species was quite difficult. We had to take on additional editorial help with this group as well, and bringing in Tom Lacher to help was a very successful move. Lynx handled the problem of splitting the Order Rodentia into two volumes very well. Polling the subscribers and making sure that people were willing to invest in two volumes rather than trying to cram everything into a single volume was very effective. Support for using two volumes to allow us to provide a much more complete survey of Rodents was overwhelming. Ultimately, we were able to involve a much larger contingent of authors to provide the necessary expertise to cover this huge Order properly.

What is your favorite HMW volume based on the groups included?

What is your favorite HMW volume based on the groups included?

I think my favorite will always be the first volume, on Carnivores. That was the one where we all learned how to work together, and the one where I was involved in every word of the text, of the photo captions, the species accounts, and of the need to establish all of our editorial standards. Amy Chernasky was indispensable in all of the early volumes. She was my main contact at Lynx, and she was incredibly responsive to my every request, night and day. She was extremely good at corresponding with authors once I had convinced them to participate. Albert Martínez provided a keen editorial eye, and made sure that I didn’t miss anything in the early days of the project. He brought an amazing amount of expertise from his work on HBW, and we had to work together to adjust our standards and norms to accommodate differences in how mammalogists and ornithologists worked. Albert was unfailingly courteous, responsive and willing to listen to my arguments and suggestions about everything and anything editorial.

With the upsurge of modern molecular biology techniques, taxonomy has been under a revolution during the last two decades; how has this affected the content of HMW?

The molecular revolution exploded exactly at the same time that we were trying to produce HMW. Although we had a really good taxonomic backbone for the project from MSW, the taxonomy of all mammals was changing so rapidly that we had to adjust on the fly from volume to volume. The first volume, on Carnivores, was relatively easy, in a way. Carnivores were quite well known, and the taxonomy had been more or less stable, for some time. There were modern changes, to be sure, but it was relatively simple to stay on top of them, and to allow our experts to update things as necessary.

This changed with Volume 2, on Ungulates. I desperately wanted Colin Groves to be the lead author on the Family Bovidae, because he was not only the world’s leading expert on the group, but he was writing a book on Ungulate Taxonomy at exactly the same time we were producing our volume. I knew we wanted to use Colin’s new phylogeny, which was heavily based on the new molecular findings, and also was, in a sense, anticipating our steady move towards a more modern, genetic species concept. Colin was extremely busy, and I made a strategic decision to involve Chip Leslie in the Bovid chapter. I knew Chip from his editorial efforts with the Journal of Mammalogy, and he proved to be the ideal person to work with Colin to bring the chapter, and the volume, together. That work led to his heavy involvement with later volumes as well, and he has been a key player in the project for a long time now.

Our new molecular toolkit has allowed us to improve our modern species concept with every group of mammals. The challenge has been to keep up with all of the changes, and to somehow provide a blend of traditional systematic arrangements with new and better ones as groups are studied at different times around the world. We made a conscious decision early on to leave the bats until the last volume, and that proved quite wise. Bat taxonomy has changed more rapidly than any other group during the life of the project, and by leaving them until last, we were able to provide the most recent classification of each family.

What measures do you think need to be implemented with the most urgency for mammal conservation at a global scale?

We tried very hard to include the latest conservation information in every volume. We knew from the beginning that providing up-to-date conservation status of each species was critical to the project. Basically, we have tried to provide a summary of the distribution, population dynamics, and conservation status of every species of mammal. This will provide a background starting point for considering all future threats to mammal species around the world. The single biggest challenge to all mammals will be global climate change. As management authorities struggle to come to grips with climate change and all of its ramifications, we are hopeful that this series of volumes will provide invaluable background data for future management plans for any and all affected species.

Finally, what do you consider the HMW series provided to the scientific community and what lines of research are needed in the future to complete the gaps in our knowledge about the world’s mammals?

Our goal was to provide a state-of-the-art assessment of our knowledge of every species of mammal in the world. We attempted to do this in the most scientific way possible, such that our information could be used easily by anyone working on mammals in the future. At the same time, we wanted to make the information as widely accessible to the general public as possible. I hope that we have provided a template for future studies of mammals. By perusing each volume, it is easily possible to discern which species are better known scientifically, and which are still lacking in many basic aspects of their biology. The rate of discovery of new species of mammals clearly suggests that we need to continue our efforts to document biodiversity on all continents. The rapid change in our ability to discriminate between species allows us to focus on groups that are clearly understudied, as documented in these volumes. Our knowledge of phylogenetic relationships, of the intricately varied lines of evolutionary pathways of each species, is constantly growing, and these volumes provide the appropriate backbone to suggest future studies in all aspects of mammalian biology.

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books