Latests posts

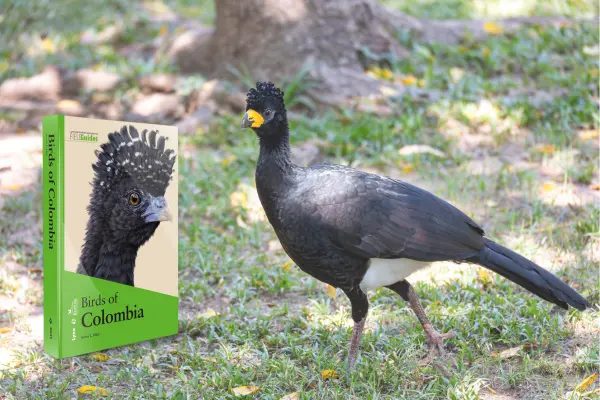

Birds of Colombia: A Journey Through the World’s Most Bird-Rich Nation

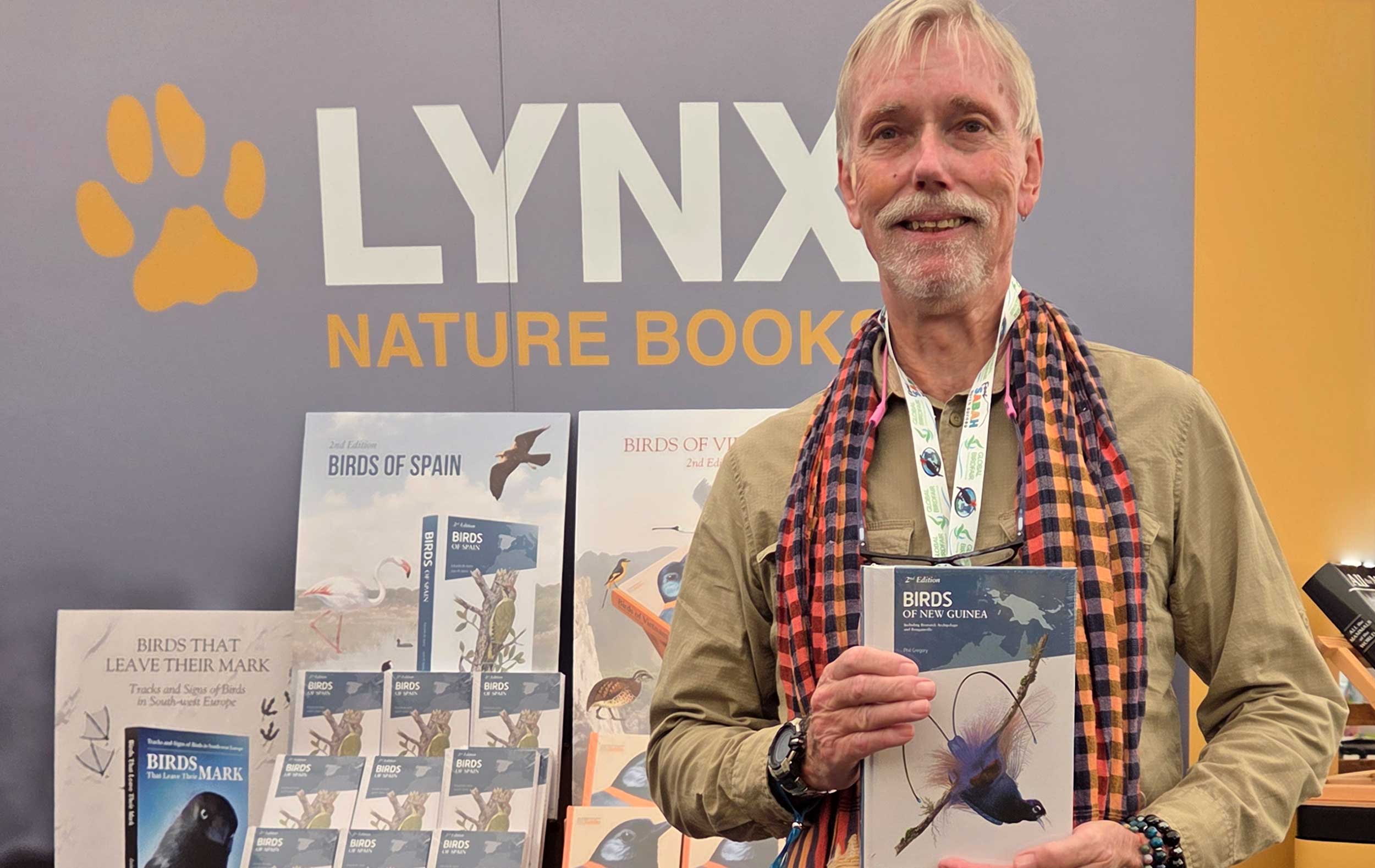

Birds of paradise and beyond: the new edition of Birds of New Guinea

Birdwatching in Spain: a guide to species, habitats and the joy of birding

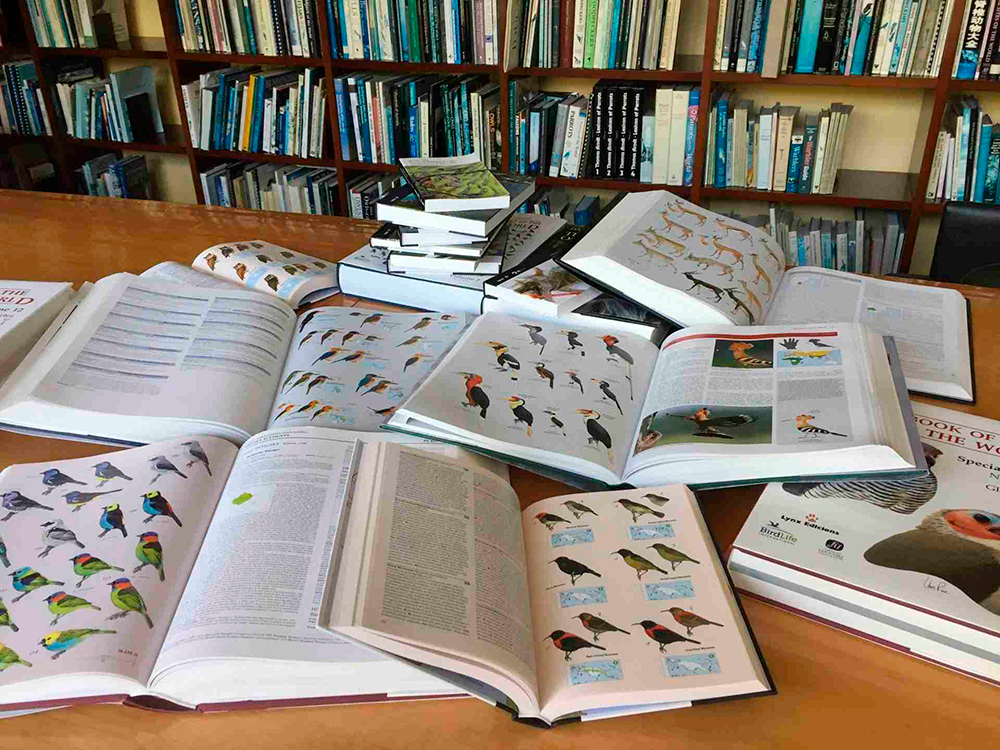

Why books matter for nature: the role of scientific publishing in conservation

Vietnam’s birds revisited: an interview with Richard Craik on the new edition of Birds of Vietnam

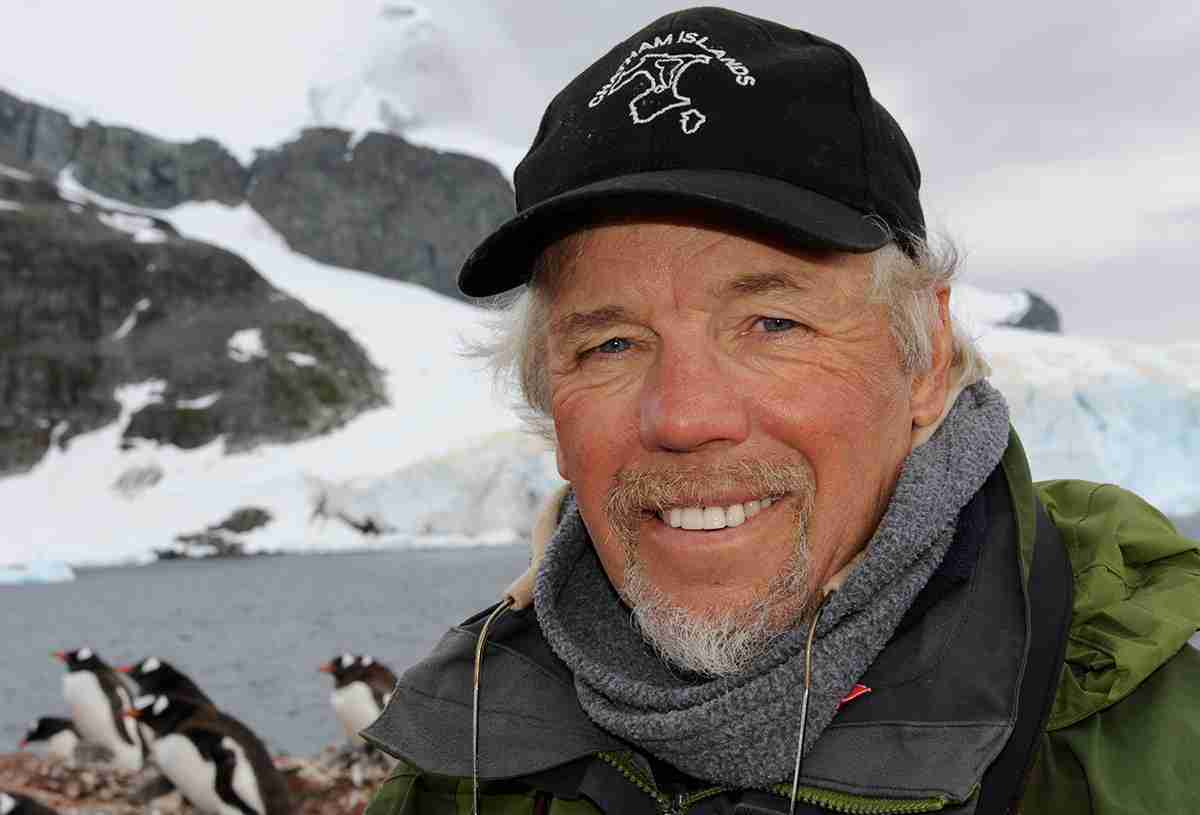

Seabirder, author and artist Peter Harrison discusses “SEABIRDS: The New Identification Guide”

Once bitten, twice shy: between the covers of the second edition of the Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago

Taming the wild world of mammalian taxonomy with Connor Burgin

Birding adventures in Indonesia with James Eaton

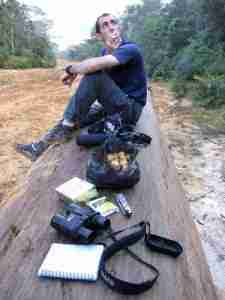

James Eaton, co-founder and guide for Birdtour Asia and co-author of Lynx’s field guide Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago tells all on birding and books in this one-on-one interview.

How did you begin as a South-east Asian birder?

After enjoying so many Autumns in the UK with those Eastern Palearctic gems, it made me wanting more, so after skipping three weeks of College time with a birding trip to Goa, India, when I was 17, I then spent a couple of months birding Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah with Rob Hutchinson during my second summer break at University when I was 20. I will never forget my first full day at Taman Negara – Rail-babbler, Malaysian Peacock Pheasant, Garnet and Malayan Banded Pittas, whetting my appetite to return as soon as uni was over!

So, with university over, my long-time close friend Rob Hutchinson decided we should go back-packing around Asia, seven months at a time for some years while working various jobs, including petrol stations, McVities biscuits, packing Christmas lights and the like back home in Derby, in between our birding forays (though this didn’t stop either of us birding the Derbyshire gravel pits or reservoirs on a near-daily basis!). In between we travelled around witnessing all kinds of sights and smells, as we birded both well-known sites and trying to trail-blaze in search of the rarest birds. As the years progressed, I settled down in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and birded from there, which has proven a great base for getting anywhere in South-east Asia.

When and why did you begin to include unexplored or less well-known islands and continental spots in your trips?

The moment I started back-pack birding around Asia in my early 20s. The thrill of a new discovery, which includes something as simple as an unknown potential birding area, and finding something worthwhile there beats any kind of birding in a well-known site for me, so as I gained experience and learned more, the bigger the exploration, the bigger the thrill. Once you get a taste for something new, it leaves you wanting more, and realising there is still so much to find and learn. Today we see so few younger birders actually continue with this, instead opting to visit the same birding sites as everyone else, and even using the exact GPS waypoint to look for species – birding seems to be turning more into twitching despite access now being better than it ever was to other sites.

My exploratory trips actually started with my first trip after University, as Rob Hutchinson and I went in search of some of the least-known species in the Philippines, finding birds in places that even today are very seldom visited, such as Luzon Jungle-flycatcher at Mount Pulag (it hadn’t been seen for many years, or after our sighting). We birded the island of Samar, which hadn’t been well-birded at all in modern day, finding plenty of Mindanao Bleeding-hearts.

Actually, I’ve probably seen more of the rare birds than the common Philippine endemics (embarrassingly, I still haven’t seen Luzon Shama or Chocolate Boobook, yet I’ve seen Whitehead’s Swiftlet and Calayan Rail!).

In recent years it’s because I have wanted to find either new species to science, or rediscover long-lost species and push the boundaries of what is currently known. Using Google Earth as a tool to decide where to go birding – the idea of planning this way, doing your homework, then actually getting on site and birding, gives me a great deal of satisfaction – I’m always keen to promote others doing likewise. My first real success with Google Earth was Christmas 2010, visiting the island of Simeulue, off Northern Sumatra. I had read of the Critically Endangered Silvery Woodpigeon being found there in 1901, however, only one birder I knew had been since, Filip Verbelen (another birder who loves adventure), so I set about looking on Google Earth for a suitable vantage point. Jotting down the waypoint, I headed there on Christmas morning – the very first bird I found was the woodpigeon, perched – the first confirmed sighting for a very long time! From that moment on, I’ve continued to bird that way as much as possible.

In your bird guide Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago, what would you highlight as the most remarkable things you are offering as new knowledge to the reader?

Four things come to mind:

- Identifying the most difficult of complexes in the clearest possible way, which has been missed by all reviewers, unfortunately. Previously, the sparrowhawks (of all ages) and hawk-cuckoos as examples were seen as extremely difficult, but we feel we have managed to makes all ages and sexes identifiable. No other field guide offers such detail for these groups.

- Vocalisations – we have pooled together our years of field experience and personal sound recordings (and also listened to every single recording on Xeno-Canto, IBC and Avocet from the region – thank you fellow recordists!) to try and make every vocalisation available to the reader with our painstaking transcriptions, in an attempt to make more species identifiable to the reader than ever before.

- Taxonomy – our taxonomy is radical and controversial, we are aware of that, but, this is because Indonesia has been largely left behind in taxonomy and we have used our field experience and research of peer-reviewed papers to bring it forward, using the same techniques used previously in the Neotropics. Since the publication of the field guide, we have authored many peer-reviewed taxonomic manuscripts that have aligned with the field guide that have been accept by Worldbirdnames (IOC), and if you compare that now with our field guide, it no longer appears as radical as at publication, and we hope this continues, and more will follow too!

- Following on from taxonomy, the introduction of the ‘limbo split’, enabling the reader to be more aware when birding within the region of particular distinctive subspecies to look out for when previously they may have ignored and not put an effort into seeing it. We want to keep the field birder as informed as possible, so it’s more than just pretty pictures, but a real guide in the field for the observer.

How was the input of your co-authors of the bird guide, Bas van Balen, Nick Brickle and Frank Rheindt, necessary to improve the final result of the book?

We compliment each other with our different skillsets, but equally we are brought together by our love for field birding. We’ve all spent many years birding extensively in Indonesia, as a hobby, but Nick has worked in the region in the name of conservation and is also well skilled at pooling together information. Bas is a very keen sound recordist, as well as a wonderful Indonesian ornithological historian, while Frank is one of the foremost Avian phylogenetic professors, with a particular interest in Indonesia. This gave us a unique opportunity to have an author with a particular skill for each aspect of the writing.

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books

Copyright 2026 © Lynx Nature Books